Trapper's Tales: Early Stories From Yellowstone

“Yellowstone!” This word alone, even today, conjures up otherworldly images in one’s imagination. It is a name known around the world. While there are other thermal areas, such as in Iceland and New Zealand, nowhere else does it all come together like it does in Yellowstone. Not only are there geysers and hot springs, but thundering waterfalls, deep, colorful canyons, a beautiful, pristine lake and an abundance of wildlife.

The first humans to experience Yellowstone were those of area tribes. Yellowstone was certainly known to the Crow, Shoshone, Bannocks, Blackfeet, Salish, Nez Perce, and others. Contrary to popular myth, Native Americans were not scared of “evil spirits” there, but probably viewed this special place as sacred. This might explain the lack of any accounts or information from early explorers about Yellowstone passed on by the indigenous population of the upper Yellowstone Country. Perhaps, seeing the incoming whites as not sharing their spiritual values, they remained silent and tried to keep it hidden as long as possible. There is one Shoshone-Bannock legend about Yellowstone and that is about the creation of the Snake and Yellowstone Rivers. The story contains no reference to hot springs and geysers.

It is somewhat generally accepted that the first white person to lay eyes on the wonders of Yellowstone was John Colter over the winter of 1807/1808 (although, later some French trappers claimed they were first). Colter, one of the first mountain men of the West, was a member of the Lewis and Clark voyage of discovery. In tracing their route back to St. Louis, the expedition arrived at the Mandan Village (North Dakota) in the summer of 1806. There they met two frontiersmen who were headed into the upper Missouri River country in search of beaver furs. The captains honorably discharged Colter early so that he could lead the two trappers back to the region they had explored.

This association was short-lived, and in 1807 Colter once again headed for civilization. About one week short of St. Louis, he ran into Manuel Lisa, a founder of the Missouri Fur Trading Company, who was leading a party of prospective trappers westward. Among the band were George Drouillard, John Potts, and Peter Weiser, whom Colter knew as former members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Colter once again decided to return to the wilderness. After helping to establish a trading post at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Big Horn Rivers, Colter struck out alone in search of Crow to trade with.

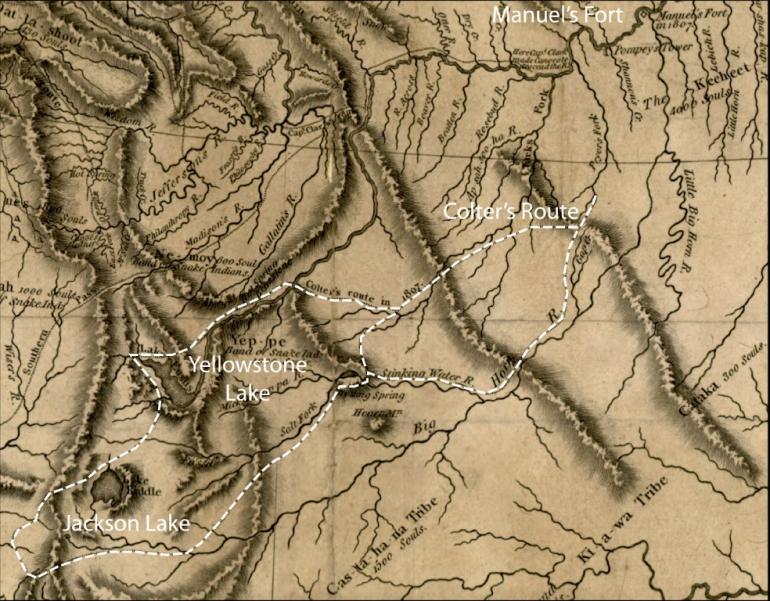

It is believed he traveled west to the area around what is now the town of Cody, Wyoming, then southwest to the Tetons and over to Pierre’s Hole in present-day southeast Idaho. From there he crossed back and moved along both Jackson and Yellowstone Lakes, observing many hot springs and geysers. He traveled over 500 miles in the dead of winter, in a region in which nighttime temperatures in January are routinely −30 °F. His route later appears on Captain Clark’s 1814 map of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, though clearly, there are some inaccuracies.

In the nineteenth century, there was no Netflix, Instagram nor Tik-Tok (obviously), so people entertained themselves with old-fashioned storytelling around a campfire. If you could tell a great story, usually full of colorful embellishments, you were a hit. So when Colter returned, everyone enjoyed his telling of the fantastic things he had seen. However, few really believed his reports of geysers, bubbling mud pots and steaming pools of water. His description of these features were often ridiculed at first, and the region was somewhat jokingly referred to as "Colter's Hell."

Colter opened the way for other would-be trappers and in 1822, at the age of 18, Jim Bridger, another legendary mountain man, signed on to a trapping expedition to the upper Missouri River. For the next 20 years or so, Bridger grew to become one of the most well-known and respected trappers of his period.

Fearing competitive pressure from the Hudson Bay Company to the north, Bridger instituted the annual fur Rendezvous. These were multi-day “festivals” that brought together independent trappers, Natives from many tribes and Bridger’s fur trading company. Furs were exchanged for cash and provisions. It was the major social event of the year. Whiskey flowed, and no doubt tales were told around the campfires, many of them probably very “tall.”

In 1825, Bridger led a group of trappers on travels across southwest Montana and down to the Great Salt Lake. It was on this trip that he first experienced the wonders of Yellowstone. Surely, it must have been at his next Rendezvous gathering that Bridger first started spinning his yarns about Yellowstone. Like Colter before him, the more seasoned trappers did not believe him. For the “greenhorns,” new to the wonders of the American West, he laid it on thick. Believed or not, he surely would have had a captive audience around the fire.

Although Bridger was illiterate and could not write his stories down, others sometimes did. He also had a sharp memory for the lay of the land. He remembered routes he took and things he saw, which served him well when he guided later in life. His descriptions of Yellowstone eventually reached the ears of a reporter for the then highly respected Kansas City Journal. The editor refused to publish these stories for fear “he would be laughed out of town if he printed any of Old Jim Bridger’s lies.” This disrespect of his accounts of Yellowstone seemed to have pushed Bridger to embellish the stories even more. If no one was going to believe him, then may as well make them absolutely fantastic. And so, his reputation for storytelling grew.

On that first trip, it seems Bridger led his troupe through Sylvan Pass from the east to the canyons of the Yellowstone River. He told friends that there was a river that was hot on the bottom (Firehole River), petrified trees (with petrified birds still roosting on petrified branches), a dark glass cliff (Obsidian Cliff), and a place on a great lake where one could catch fish in the cold water, then cook them in the hot springs without having to move or take the fish off the hook.

But Bridger could be quite factual and accurate when he wanted to be. Captain John Gunnison, who helped survey the valley of the Great Salt Lake in 1849, spoke of Bridger’s descriptions of Yellowstone Country: “A picture most romantic and enticing….A lake 60 miles long, cold and pellucid...The rivers issue from this lake and for 15 miles roars through the perpendicular canyons...Waterfalls are sparkling, leaping and thundering down the precipices, and collect in the pools below.

“On the west side...the ground resounds to the tread of horses. Geysers spout up 70 feet, with a terrible hissing noise, at regular intervals (Old Faithful). In this section are the great springs, so hot that meat is readily cooked in them; and as they descend on the successive terraces, afford at length delightful baths.”

At other times he could spin his experiences into quite fanciful yarns. While not all the crazy stories that have been attributed to Bridger were actually his, there are three or four that do seem to be verifiably from Bridger himself. Those concerned petrified forests, “Hell-close-below” and the stream-heated-by-friction.

Overlooking the Lamar Valley in the northeast of the park is Specimen Ridge. This is where you will find Yellowstone’s petrified forest. One of Bridger’s fireside yarns he liked to tell involved a mountain that was cursed by a Crow medicine man. The curse instantly petrified everything on the mountain. All forms of life remain as they were at the instant of the curse—trees, sagebrush, grass, prairie fowl, elk, antelope and bears. The flowers were even caught in blooming colors of crystal, and birds soared with wings in motionless flight. Torrents of water and the mist from them were caught in arrested motion, as if carved from rock by a sculptor’s chisel. The air floated with music and perfume, and even the sun and moon shone with petrified light!

Bridger would also sometimes tell a story of watching a couple of Indian braves riding on horseback in front of him, crossing a thermal area presumably. “They hadn’t gone very far before the crust of the earth gave way under them, and they and their ponies went down out of sight, and up came a powerful lot of flame and smoke. I bet Hell was not very far from that place.”

One day, Bridger said he discovered an ice-cold spring near the summit of a lofty mountain. He would describe how its waters flowed down over a long, smooth slope, where it gained such velocity that it was boiling hot by the time it reached the bottom. Bridger explained this was due to friction, just as rubbing two sticks together produce heat.

Author and former captain Eugene Ware met Jim Bridger in the 1860s and gives the following account: “Major Bridger...told stories in such a solemn and firm, convincing manner that a person would be likely to believe him…. He wasn’t the egotistical liar that we so often find. He never in my presence vaunted himself about his own personal actions. He never told about how brave he was, or how many Indians he had killed. His stories always had reference to some outdoor matter or circumstances...He told each story so often that he had got it into language form, and told it literally alike. He had probably told them so often that he got to believing them himself.”

Stories of Yellowstone grew and grew over the course of the mid-nineteenth century until the government sanctioned expeditions to explore and map the area and finally set the record straight about what was actually there. The most notable of these were the Washburn Expedition of 1870 and the Hayden Expedition of 1871. As a result of the information brought back by these expeditions, Congress set aside the Yellowstone area as the world’s first national park.

Yellowstone now sees 3-4 million visitors per year from all parts of the world and all walks of life. For many of these people, the wonders of the park’s unique features and its utter “otherworldliness” must leave them in awe, much as it did to these early trappers. One has to wonder when these visitors get back home and begin describing what they witnessed to their friends, whether it be on a living room couch or around a kitchen table, if they are not, in their own way, channeling that same spirit of those campfire trappers’ tales of old.

Leave a Comment Here