The "Real" Cattle Queen of Montana

Who was the "Cattle Queen of Montana"?

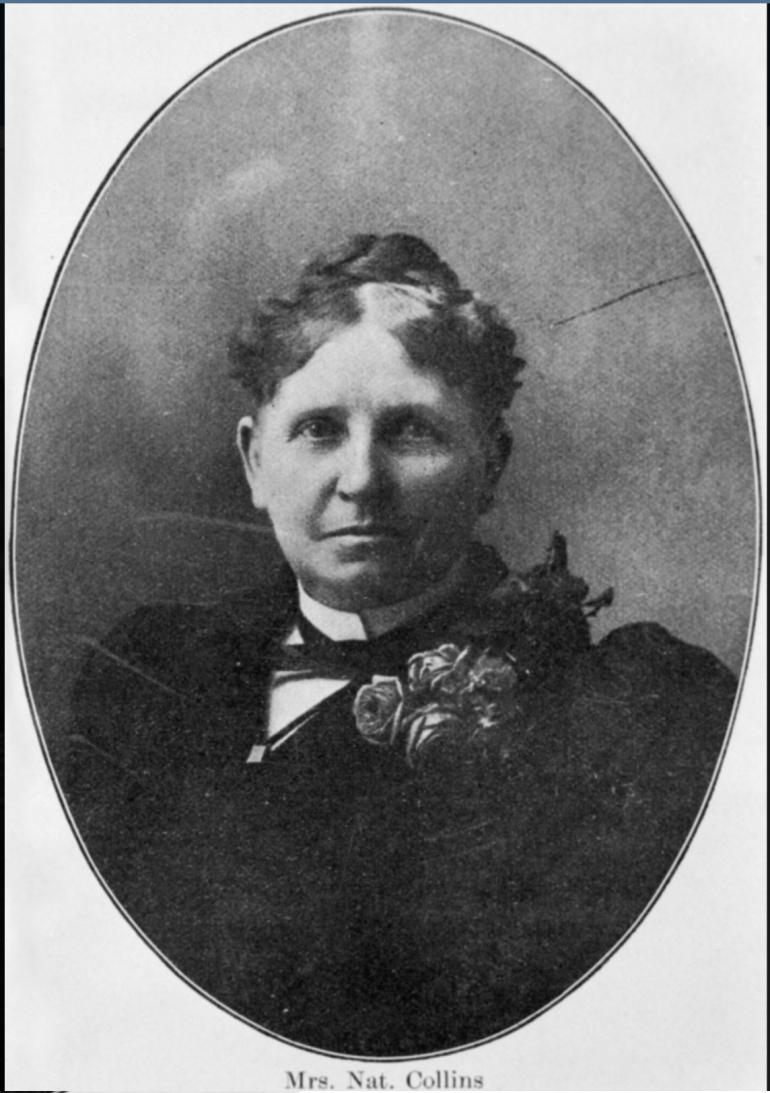

Her name was Libby Collins, but don't look to Hollywood for any sense of true history.

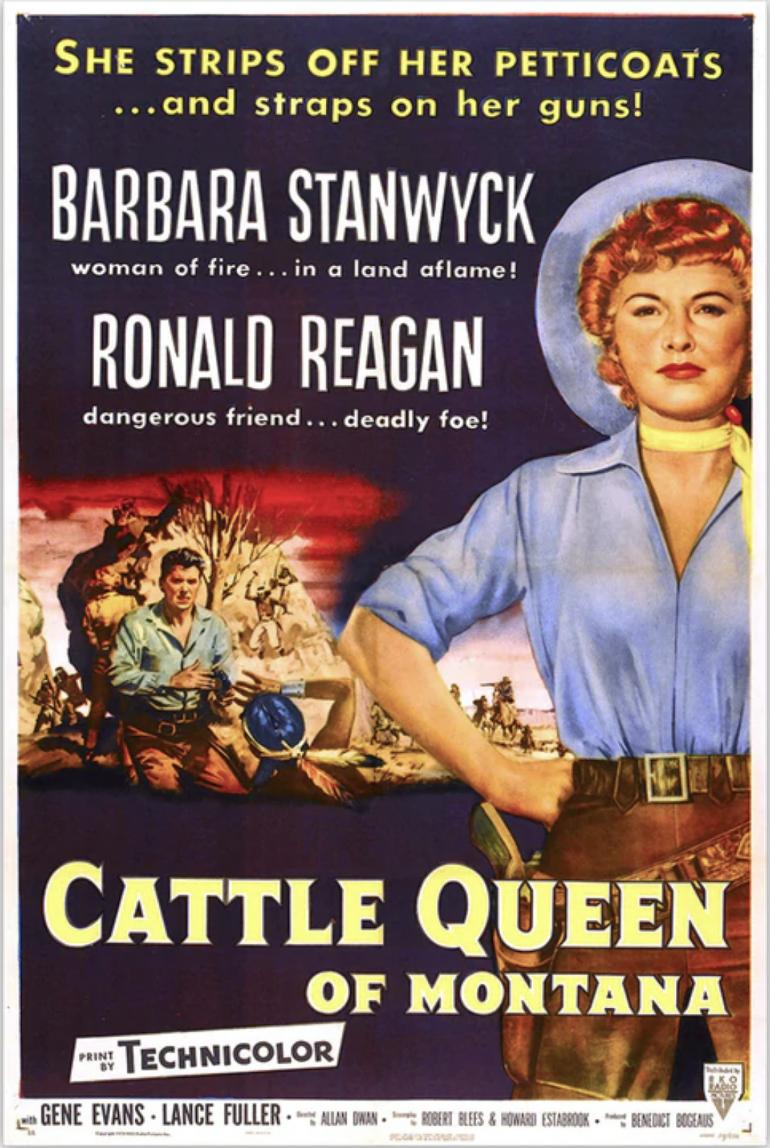

The 1954 movie by the same name, starring Barbara Stanwyck and Ronald Reagan, is a cheesy Western rife with the stereotypes common to the period. Even the main character, the so-called Cattle Queen herself, had a different name (Sierra Nevada Jones) and was from a different state (Texas vs. Illinois) than Mrs. Collins.

The real Cattle Queen of Montana had a life of true grit, achievement, and a sheer will to survive whatever circumstances befell her. She once described her life as being "buffeted about by circumstances, hurried hither and thither by the decrees of Fate and pushed forward along unknown paths by uncontrollable events." She demonstrated an indomitable spirit that the pulpy film adaptation fails to capture.

Libby Collins was born Elizabeth Smith in 1844 in Rockford, Illinois. She was the ninth of ten children. At age 10, the family moved to Madison, Iowa, considered a frontier town at the time. It wasn't long before her father caught the "gold fever" bug, and in 1855, at age 11, young Elizabeth joined her parents in the long trek for Colorado's Cripple Creek mining district in search of a better life, ultimately spending most of this time in the Denver area. The Smiths left the rest of the family behind, with some being married and settled.

It would be another eight years before Libby would ultimately end up in Montana.

She grew up quickly in Colorado. Libby did long days of back-breaking work just to survive. At the young age of 11 or 12, she was forced to become the main worker in the household, cooking for boarders while her father was off prospecting and her mother lay ill. Later, she recalled: "The task was far from being an easy one. Our food was cooked over a fireplace, and at times it would seem that my face was fairly blistered from the heat and my eyes blinded by the smoke. But to complain was never one of my traits of nature, neither was the expression 'give up' ever included in my limited vocabulary, and I struggled on, hoping that better times and more comforts would soon fall to my lot."

Come they finally did, but only much later in her life.

At age 16, on a fateful journey back to Iowa for some needed rest, she was kidnapped by a hostile Plains tribe and held captive for six months. Libby became a protected, prized possession of the Chief while watching less fortunate captives perish in various gruesome ways. For several years after, she was a camp cook for a wagon master, making the trek back and forth between the Rocky Mountains and the Missouri River, enduring choking dust storms and blinding blizzards time and time again. "The hardships of camp life are only understood by those who have experienced them in person," she wrote. At the age of only 19, she was promoted to "scout" on the wagon train that brought her to Montana in 1863. It's hard to imagine how rare it would be for a female to be a scout, let alone a 19-year-old, but such was the trust she garnered from the experiences and skills she accumulated by that young age.

She lived for a time in both Virginia City and Bannack – the two rowdiest mining boomtowns in Montana.

She was a firsthand witness to the lawlessness there and the subsequent rise of the vigilante movement that finally brought a semblance of peace to the area: "As if by magic, the face of society was changed within a few short weeks." All alone, she made her way as a mining camp cook, endearing herself with the miners she served. They loved her so much that they all pitched in and gave her a 100-pound sack of flour for Christmas – not a cheap item in Virginia City in those days.

Twice she survived disasters and near death that left her penniless with just the clothes on her back.

Once during her time in Denver, her home was swept away by a flash flood. Later, in Helena, while working as a well-paid under-nurse for a prominent physician, the great fire of January 1874 took all her belongings and money. Though in dire straits each time, the kindness of the many people she befriended along the way repaid her with a way forward, another chance to start over.

The Helena fire actually brought her and her soon-to-be husband together when she went back to being a camp cook at his mine. She married Nat Collins on New Year's Eve, 1874, at the age of 30. After a couple of years and some unfortunate life-threatening accidents, they sold the mine and decided cattle ranching would be a safer and more profitable business, so they moved to Teton County on the Rocky Mountain Front near the present-day town of Choteau.

Once again, loneliness set in. Settlers were few, and she was the first white woman in the valley; her daughter, Carrie, was the first white child born there. She quickly made friends with the local Blackfeet, becoming fluent in their language and exchanging skills, such as beading and healing. The Collinses even adopted two Blackfeet sisters who were orphaned when their parents were murdered.

Although it was a happy time in the Collinses' household, she yearned for other women who spoke English. Over the years, as settlers started to move in, many sought out her nursing, healing, and midwifery skills as there were no doctors in the area at that time. Her open, caring demeanor earned her the nickname of "Auntie Collins."

Their cattle flourished in the Teton Valley, and their herd grew rapidly in size. Libby figured they would increase their profits if they sold their cattle in Chicago rather than locally. Plans were in place to drive the sale herd to the nearest railhead in Great Falls, a four-day journey, and from there on to St. Paul and then to the Chicago stockyards.

Once again, things did not go as planned. Nat fell ill and could not go, so she took it upon herself to undertake the adventure herself, knowing full well no woman had ever done this before. The first obstacle was the shipping company in Great Falls, which would not ship her stock until others came to fill all the cars – a ten-day wait. Secondly, women were not allowed on the train with the men.

Not being one to accept "no" as an answer, she had a telegraph sent to the St. Paul headquarters of the shipping company explaining her situation. The reply read: "provide for the comfort of Mrs Nat Collins…in every way and treat her with respect due a lady, under penalty of discharge upon failure to do so." Not only did she convince the railroad company to accept her, but she was given a first-class ticket for the ride from St. Paul to Chicago!

As she boarded the train with her cattle, a hearty cheer went up from the onlookers: "Success to Auntie Collins, the Cattle Queen of Montana." The name stuck. Later she wrote: "I have, during my life, passed through many a discouragement and have been overtaken by many a disheartening event but, without exception, I have never experienced a more trying time than during those ten days of waiting before I finally saw my cattle and horses loaded and safely started on their journey, and found myself sitting bolt upright on the leather cushions of that hard-riding caboose with the much dreaded railroad men about me."

Between her father and brothers prospecting in Colorado and her work in the Montana mining camps, the lure of mining was not too far below the surface. Between the late 1880s/early 1890 (accounts differ), Libby staked a claim in what is now the west side of Glacier National Park. She raised investment money and spent three summers chasing a quartz vein for copper before giving up. Today, the tributary of Mineral Creek in the park near her abandoned mine is named after her, "Cattle Queen Creek.

Later, shortly after the turn of the century, while in her 60s, "the call of gold was sending its alluring thrill through the land." She once again "felt the desire for excitement burn in [her] blood." She made the long journey – first overland to Seattle, then by ship to Nome, Alaska. However, as with most of the throng that flocked to the Alaska goldfields, things didn't "pan out." With great disappointment, she headed back to Montana. Surely, the first time on a sailing ship headed north through pods of dolphins and whales must have been an adventure worth seeking, even if it didn't bring home the yellow metal she sought.

Source: Rotten Tomatoes

A few years after her return, her husband, Nat, passed away in 1909, and with her own age advancing, she soon left the ranch to her daughter's family and moved into town.

Eventually, she would winter in California to get away from the harshest of Montana's weather while going on occasional lecture circuits, talking about her life experiences. She passed away in 1921 in her Choteau home.

Throughout much of her life, Libby Collins endured hardships extreme even by nineteenth-century standards, that we, today in the twenty-first century, would find nearly impossible to comprehend.

Through it all, she remained strong, resilient, and above all, adaptable as she persevered through "Fate's decrees." Libby never lost her compassion for the sick, injured, and those less fortunate than her. She was not just a witness to the unfolding history around her but an active participant in making it. Now, that's worth a movie!

- Reply

Permalink