Three Snapshots of Underwater Montana

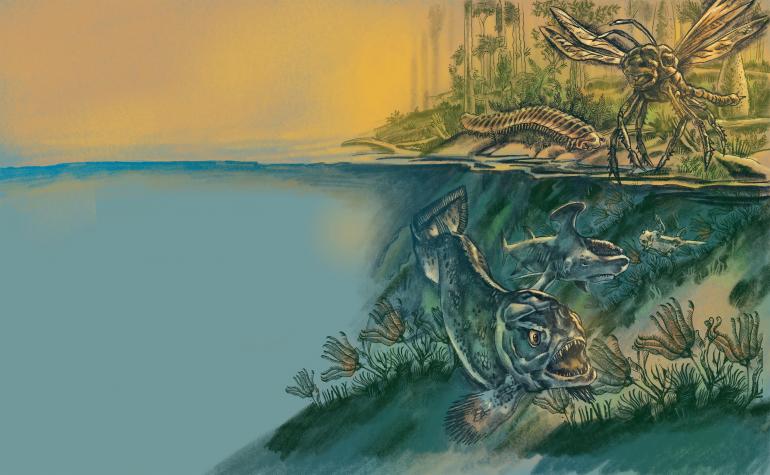

300 Million Years Ago, in the Carboniferous Era

Long before anything resembling a dinosaur left any tracks through our state, most of Montana was under the sea, either deep and dark or shallow and swamp-like. It remained that way for millions and millions of years.

There were, however, some mountain ranges just beginning to form, like the ancestral Rockies and the Appalachians, far to the east. Vast swaths of Pangea, the continent on which we would be standing even as it collides, in geologic slow motion, with the ur-continent of Gondwana, are flat, shallow seas covered in swamps.

A world of oceans speckled with dots of damp, green land, the planet is largely temperate, averaging in the mid-sixties degrees Fahrenheit. Nothing competes for the skies but stars and clouds, but now and then, an insect, or even a few kinds of fish, can take to the air for a moment and soar a few feet over the ground for their exertions.

If we were to step out of a time machine and into that Montana, we would recognize almost nothing of our world except for water, sky, and green plants.

And if a creature from the Carboniferous Era were taken from oceanic Montana and dropped in our own lakes and streams, there would be little to remind it of home—not even the water, which now contains significantly less oxygen. A prehistoric fish might well choke to death on our thin water.

You or I would gasp at the richness of the air, which contained 80% more oxygen than it does now. We could take in a great deal more oxygen with each breath, although the smell of all the flora and fauna might well have been overpowering.

Oh, and we can't neglect to mention that all that oxygen has had a curious side effect on the insects of the period, which sometimes resemble monstrously large funhouse versions of our own bugs, an entomophobe's fever nightmare. Relatives of the dragonfly called the Meganeura grew to have 2.5-foot wingspans, and you would likely have been able to hear the tell-tale zipping sound that announced its flight as it stalked smaller insects and amphibians. Decidedly not smaller, and therefore not at risk, at least from the dragonflies, were the eight-foot-long millipedes which crawled along the floor of what ground there was, eating whatever a titanic arthropod ate. You might also watch out for the two-foot-long scorpions.

Yet predominantly, it was fish that ruled Montana in this epoch. Sharks had just appeared, blooming into a startling profusion of creatures much stranger than our relatively narrow varietals. Most of those branches of the modern shark's family tree are long extinct, pruned by time. Even sharks had to fear some bigger predators, like the Rhizodus hibberti, a fish-like creature that grew to over 20 feet in length. The apex predator of the early Carboniferous, they were able to make a dinner out of nearly anything that walked or swam.

You might reel as you took it all in, hands protecting your head from the dog-sized insects, hearing the alien calls of a hundred strange creatures you've never seen before, all provided you were lucky enough to find a patch of land. There are also plants everywhere, mostly seed ferns with small, intricate leaves that flutter when disturbed by the breeze. Perhaps some unrecognizable fruit hangs in strands like colored pearls, but there are no flowers in sight, and there won't be for 150 million years or so.

In the vast shallows, forests of crinoids wave in the water as fish dart in and out of their feathery arms. For sheer biomass, in some places, as near Lewistown, crinoids were so numerous that their fossilized remains later left blankets of limestone fossils, the compressed remnants of a billion simple, ancient lives.

The sky turns slate as thick, billowing clouds gather darkly in the east, blowing in from the Panthalassic Sea. The insects hush, suddenly, moments before sheets of warm rain begin to fall, dappling the leaves and disturbing the surface of the waters.

19,000 Years Ago...

It is quiet too, here on the edge of Glacial Lake Missoula. We stand on the beach of the lake, which happens to lap at the side of Mount Sentinel. As we look out to the horizon, almost everything is underwater except for a few small islands: the peaks of mountains.

The water is a beautiful turquoise blue that resembles a tropical lagoon, the result of white rock flour mixing in with the water as the summer sun melts the glacier. The dust of stone pulverized as the glacier scrapes across bedrock has created the nutrient-rich conditions for large blooms of algae, adding splotches of unlikely color to the surface and giving the air a tangy, leafy smell.

Somewhere to the east, there are strange animals - giant bears and bison, saber-tooth cats, black-winged birds larger than any eagle—living and dying alongside creatures we would recognize today.

The gigantic body of water in front of us is relatively recent in geologic terms, created over a half a century or so when the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, a solid block of ice with boulders and rocks captured in it, slid far enough south to choke the mouth of the Clark Fork River at Lake Pend Oreille. There, an ice wall 4,000 feet tall and extending north to the Arctic Ocean has come to rest.

Even out here, 180 miles away from Lake Pend Oreille, the water conducts some of the commotion created by enormous chunks of the ice wall calving from the central mass to fall, crashing, into Glacial Lake Missoula.

The flow of the Clark's Fork has backed up where it meets the glacier, pouring water into a basin that reaches from Missoula to Deer Lodge and beyond, filling some 2,973 square miles of land with over 500 cubic miles of ice-cold water.

But the air around you is warm, and that far-off wall of ice is melting. As it melts, the water around the wall itself churns with the current of the river, and iceberg calves grind away at it in the flow. One day soon, the unfathomably high and seemingly impenetrable ice dam will give way, spilling this huge glacial lake across Idaho, Washington, and Oregon with prehistoric ferocity.

All that water will wash the earth of anything organic, taking the faces off mountains, spraying through narrows, shaping the land with its flow, and, ultimately, creating a wasteland. Glacial Lake Missoula will empty itself over three tumultuous days. It's hard to overstate the devastation it will bring. Then, it'll do it again and again as the Cordilleran Ice Sheet resettles, creating a new ice dam and refilling Glacial Lake Missoula, only for the inevitable to happen again as few as 20 and as many as 100 times.

But all of that latent destruction seems impossible from here on the shore of the lake. A body of water this large feels infinite and eternal as it slowly fills the mountains.

A piece of ice the size of a house bobs among the peaks, working its way south. As it rolls in the freezing water, its weight resettling as the sun warms any surface exposed to the sun, the light catches and reflects in spiky glints. The gentle chuckling of the waves is the sound of a torrent building drip by drip.

Today...

On some days when the water is low in Hap Hawkins Lake, you can still see parts of Armstead, Montana—a bit here and there of the old U.S. Highway 91, a section of submerged track that once belonged to the Union Pacific Railroad, even some foundations of buildings in which the people of Armstead used to live, sleep, worship and do business.

Armstead's not quite a ghost town in the traditional sense. Generally, we think of a ghost town as a place where economic prospects dried up, so to speak, or something made living there untenable until people started to move away. But Armstead, founded in 1907, was an entirely viable community when it was abandoned. What happened to Armstead happened all at once.

In 1962, the establishment of the Clark Canyon Dam created a new body of water over the townsite of Armstead.

The location is steeped in history—it's close to Camp Fortunate, where the Lewis and Clark expedition encountered Cameahwait, Sacagawea's brother. According to the indispensable Names on the Face of Montana by Roberta Carkeek Cheney, "The town was named for Harry Armstead, a miner who developed the Silver Fissure Mine at Polaris." In addition, it was an important terminus for the Idaho-to-Butte stretch of the Gilmore and Pittsburgh Railroad.

In an old picture, townspeople look on with apparent excitement as the first blast signals the groundbreaking of the dam on October 1st, 1961. By that time, many of the original buildings had been moved, and its townspeople had resettled. Construction of the dam was completed in 1964, after which the location where they and their families had lived for a century was filled with water and stocked with fish.

In the crowd, you can see a toddler wiggling in his father's arms as he cranes to see the explosion. A man in the foreground laughs as he turns to address an unseen listener. A few children, already bored with the transformation of their landscape, begin to wander away from the adults toward some more enchanting distraction. Everyone is dressed as if for church, in their Sunday best, they used to say. The air seems light and celebratory.

And yet the occasion captured in the photograph must have been bittersweet— the dam would allow downstream irrigation and protect against flooding, but for many, it also meant saying goodbye to their homes, or at least the place their homes had been. In some cases, families had been living there for generations.

But today, in spring and into summer, the reservoir is a popular fishing location. A cool breeze blows, and boats play across its surface. Under the lake, the location where Lewis and Clark bartered with the Shoshone lies inundated. And not far off, the town of Armstead's few remaining buildings, like the sturdy old post office, come apart slowly as rainbow and brown trout wend their way in and out of dark, deteriorating rooms.

There is no change without loss. If Armstead hosts any ghosts today, they make their forlorn rounds underwater.

Leave a Comment Here