Conquering the Divide: Early Aviation in Montana

For thousands of years, no person had seen Montana's mountains from above—how the trees resolve into green speckles on slate gray patched with blinding snow. Only birds had ever seen their own shadows cast, far below them, on the rooftop of that landscape.

Human beings had to wait until the late 19th century when the pursuit of physics and engineering brought the dream of controlled flight almost within grasp. All over the world, engines, pedals, foils, and wings were combined in strange and unprecedented ways, chimeric machines composed of odd parts. Most were death traps. Some achieved a degree of lift before going nose-down into rivers and fields. Then Wilbur and Orville Wright cracked it in 1903.

In 1910, the state of Montana had, of late, been the frontier. Now, as civilization encroached on all but the most secluded corners of Montana, the sky seemed to be the new frontier. Aviation was a brand new, wide-open territory—not unlike Montana herself.

But the land of Montana was very different from the flat, sandy terrain of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Her mountains were plenty arduous to cross from the ground, but her citizens had spent a hundred years or so figuring out the best ways to do that. For millennia, the art of traversing them from the air was theoretical to all Montana's living creatures, save for birds.

Now, only within the last few years, human beings could share that same, rarified view.

Montana aviation historian Frank W. Wiley described an enchanting scene:

"You could fly...at 50 to 200 feet above the terrain, see a jackrabbit burst out from behind a sagebrush, or a coyote give up the stalk on a rabbit, giving you a dirty look from yellow eyes before spinning his wheels to get away... You could check your drift with the smoke from a sheepherder's wagon as he cooked his breakfast, and see his sheep start to pile up on the bedground, too startled to move far before you were gone."

Such beguiling views were the exclusive purview of a brave few willing to sit at the controls of a machine that was at best untested and, at worst, highly dangerous. In short, to be a pilot was inherently to be a daredevil. As Wiley relates, "In those days, three accidents in one week were about par for the course."

Daredevils love a challenge, and each wanted to crack the next one for themselves. One of the most daunting still remained: becoming the first person to fly over the Continental Divide. Various hotshots and flyboys eyed it hungrily.

One of them was Eugene Ely, a masterful flyer and race car driver from Williamsburg, Iowa. He began as the chauffeur to a priest with a penchant for fast cars, in whose employ he broke at least one land speed record. He drove a delivery route in a car, raced in one, even took a job as a car salesman. His life, it seems, was to be devoted to the automobile until his boss at the latter job acquired a brand new Curtiss bi-plane. Ely figured it couldn't be much harder than driving a car, except that you had a new axis with which to contend. He crashed it, of course, but he survived, and before long he had repaired the plane and found a passion for flying that eclipsed driving.

The mountains introduced another factor dangerous for pilots to ignore: high winds. Higher elevation also meant less oxygen for the engine. Ely himself, speaking to the Billings Gazette in June of 1910, can describe the challenges of flying that high: "You see, an aeroplane loses 48 pounds carrying capacity with every 1,600 feet elevation, and as I believe the altitude of Billings is about 2,300 feet, I will lose about 145 pounds lifting power...if I can get off the ground I am almost certain I can mount to a considerable height and stay in the air for some time."

Unfortunately, on the occasion about which he was being interviewed, Ely only managed to get a few feet above the ground, maintained only for a few moments.

Undeterred, he left the state to pursue other possibilities that would, ultimately, secure his legacy. In January 1911, he made both naval and aviation history by being the first man to land on an armored cruiser, the USS Pennsylvania, thus paving the way for the modern aircraft carrier. He was only about 25 years old. His accomplishments, it seemed, would continue for decades to come. Perhaps he would be the one to conquer the Divide.

Or would it be James C. "Bud" Mars, a man with many accomplishments as a flyer? This was the man who gave Emperor Hirohito his first plane ride, and had become only the eleventh licensed pilot in the country. Not the least of his feats was being the first person to fly a plane at the Montana State Fair. Though he crashed on the first day, he survived to make demonstrations of flying in a twenty-mile-an-hour wind, and an attempt at the Continental Divide. He fell short, landing in Magpie Gulch after flying 21 miles.

The next day he tried again but hit a downdraft and clipped a boulder with the propellor. Again, he survived, after a daring rescue by a detail of soldiers from Fort Harrison, who were also kind enough to carry the plane to the road. He made no more attempts.

The city of Helena, grateful for the entertainment and displays of derring-do, threw him a dinner. The menu was duck, which as writer Frank W. Wiley points out, "was selected as being symbolic of flying."

No, it wouldn't be Mars, who would live long enough to look back at his reckless aviation days from the distance of a few decades, perhaps with a mixture of fear and awe at the things he'd done so long ago.

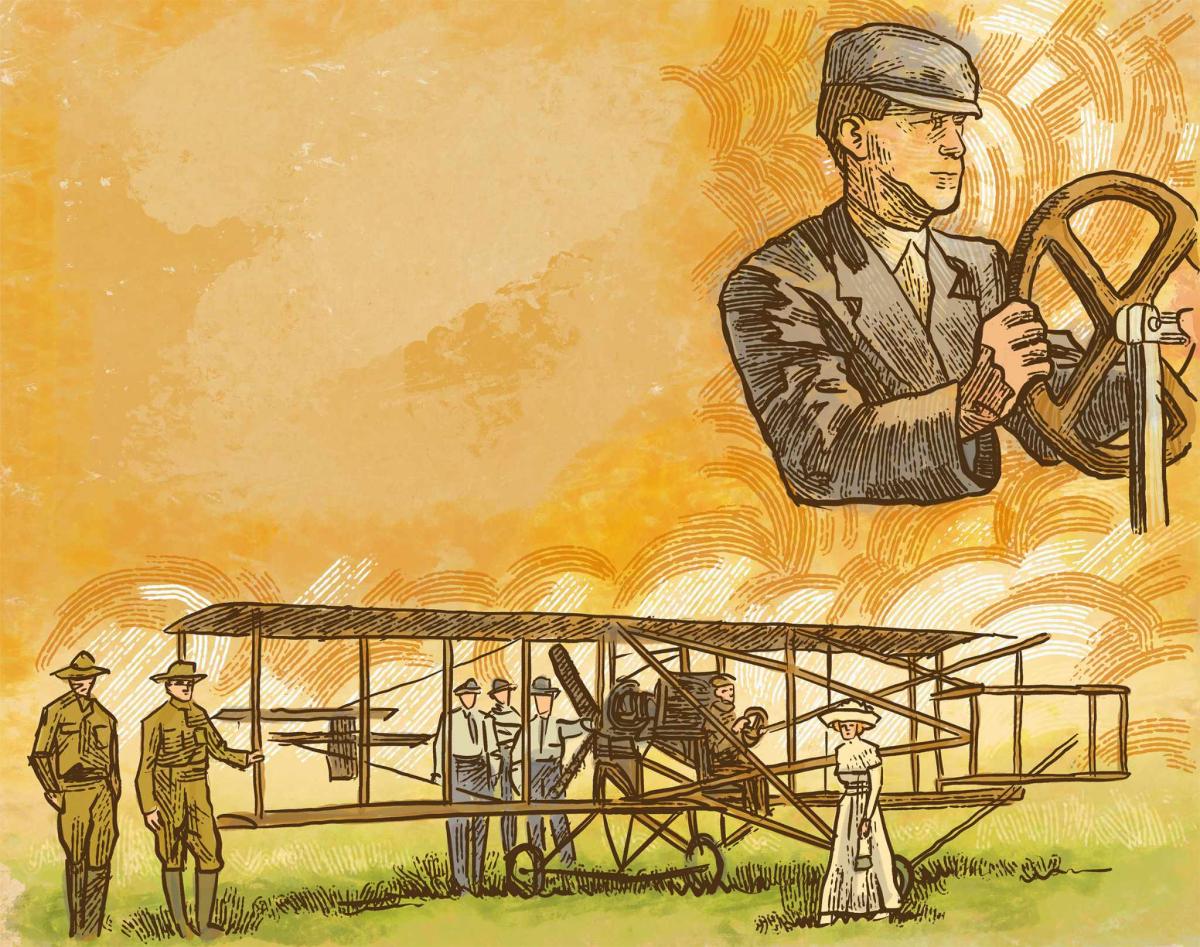

Maybe, then, it would be the unlikeliest aviator of all, the young Cromwell Dixon, who at 19 was barely more than a child and, at the time, the youngest pilot ever. Dixon's youth and his unlikely accomplishments were a great story eagerly consumed by the readers of papers across the country, who saw in him an aviator's version of the American dream; he had built his first "flying bicycle" at 14, and flew it at the St. Louis Expedition, among other venues. By the time he arrived in Montana, he even sported a sponsorship from the Curtiss Exhibition Company.

Slight, with an unassuming face hidden under checkered flat hats, Dixon had almost certainly been a child prodigy. According to stories about him, he invented little clockwork toys as a child, setting them loose on the lake to putter and move around. Like so many of the earliest aviators, he cut his teeth on ballooning, creating a silk airship filled with hydrogen which was led by a pedal-powered propellor. He named it the Moon, and he performed in the sky while his sister did vaudeville on the ground at the Louisiana Purchase Expedition. Eventually, the Moon would burn up in a fire. He would build another, and even win an award in ballooning before he would switch to airplanes. He received his pilot's license in August of 1911, only one month before his date with destiny.

All that summer, meanwhile, aviators native to Montana and otherwise continued to flirt with danger. In May 1911, Montanan George E. M. Kelly was flying over an airfield near San Antonio, Texas when he lost control. His last, heroic act was to yank his controls to narrowly avoid a group of infantrymen on the field. He crashed into the ground, dying, but he avoided any collateral damage.

And on June 20th, R. C. "Lucky Bob" St. Henry very nearly died when circumstances forced him to attempt a risky gliding landing in Mandan, South Dakota. His misadventure there detained his scheduled flight in Miles City, prompting disappointment among the locals, according to the Daily Star:

"Well, when Ralph Gilmore and his 'bunch' came in last night...they expected to remain over for the airship stunts which St. Henry proposes to put on.

"There was much disappointment, however, when the boys learned the airship business had been postponed until June 24 and 25.

"Dick Anderson and 'Hooton' Pete Wells were mad enough to 'slap leather' and 'Hooky' Bill Combs and Smith White were so savage they could have shot up the Olive hotel where St. Henry was sleeping with his boots on."

Hooton Pete, the article went on, was heard to admit, "Tell you what, fellows, I'd sooner ride the most vicious and meanest bronc in Montana than ride that airship critter."

To which "Hooky" Bill replied, "I betcher life she's no worse 'an the yeller bronc I busted up last year."

Nevertheless, St. Henry performed on the 24th and 25th with no accidents and disappeared into history—one assumes that word of his death would survive in papers or in memory. He must, therefore, have died in some more prosaic way than behind an aircraft's controls.

Across the world in France, on May 21, 1911, the pilot Louis Émile Train crashed into a group of assembled watchers, including the French Minister of War, Henri Maurice Berteaux, killing him. It was the beginning of the annual Paris to Madrid air race.

In Chicago, a bit closer to home, two aviators, William R. Badger and St. Croix Johnstone, both died on the same day, in separate plane crashes at the 1911 Chicago International Aviation Meet. Badger crashed while trying to exit a controlled dive, while Johnstone accidentally splashed into Lake Michigan after being beset with engine trouble.

In other words, aviation was a very risky business, and the Continental Divide still beckoned, begging for someone to conquer it.

Eugene Ely attempted it on June 3, before a huge crowd of lookers-on at a Butte show that, according to Frank Wiley, also included "horse races, automobile races, and motorcycle races." Another race was to be staged between Ely's flying machine race and a Stevens-Duryea car.

Eugene Ely attempted it on June 3, before a huge crowd of lookers-on at a Butte show that, according to Frank Wiley, also included "horse races, automobile races, and motorcycle races." Another race was to be staged between Ely's flying machine race and a Stevens-Duryea car.

Two other aviators were scheduled to show up, but were "unavoidably delayed," so all eyes were on Ely's attempt. He rose to over 2,000 feet above the famously "mile high, mile deep" city, high enough to perform the trick, but judged that the wind wasn't favorable for a crossing. He landed.

The next day, the capricious Butte weather prevented him from flying. On Sunday, in front of a crowd "acclaimed as the largest ever gathered in Butte," with thousands having poured in on trains from towns all over the state, Ely tried once again.

This time, the fault was not mechanical, or meteorological, but human: part of the crowd broke off and rushed the runway even as he began to take off. He turned to avoid them and somehow damaged his plane sufficiently to preclude any further attempts. The Butte crowd, as you might expect, was steamed. They made their dissatisfaction known to the sponsors of the show, who held back $1,000 in receipts to the Curtiss Exhibition Company and donated it to, in the words of Frank Wiley, "an indefinite miner's charity."

A few weeks later, Ely flew in Kalispell, staging two performances after which, Wiley says, he "praised the management for handling the crowd" in what may, or may not, have been a dig at Butte.

Ely, who was touring east to west, was now too far to conquer the Divide. He performed an impressive series of displays in Missoula to another huge crowd, but left Montana in late June to fly at a Fourth of July performance in Reno. As he left, he may well have already been planning a return the next year, provided someone didn't beat the Divide before he got the chance. As it happened, Cromwell Dixon did—and Ely would never return to Montana again.

Cromwell Dixon didn't even have his pilot's license by Ely's final attempt to fly over the Divide. His meteoric ascent to the heights of heavier-than-air aviation occurred in roughly one month, from getting his license to performing at the Montana State Fair in Helena that September.

On a clear day, at two in the afternoon, Dixon took off from the field. He had to get high enough to clear the mountains, but it was a struggle. Finally, he achieved 7,000 feet in elevation, enough to clear the mountains. The weather was clear enough for smoke from a signal fire to be visible from Blossburg, a small town across the Divide. Watching it intently, Dixon followed the smoke over the spine of the Rocky Mountains and successfully, safely set down at Blossburg, where enraptured onlookers congratulated him with a $10,000 prize.

He had done it—the Continental Divide had been tamed from the air. The flight had taken him just over a half hour. His eyes had beheld what no other human’s ever had.

After sending a telegram to the Curtiss Exhibition Company to let them know he had been successful, he got back into his plane and took off again. A half hour or so after that, he landed at the Helena Fairgrounds, where another crowd greeted him as the conquering hero he was.

A month later, Cromwell Dixon sat at the controls of his plane at the Interstate Fair in Spokane, Washington. He took off and flew. No one present could have been unaware of his history-making flight a couple of states over. They wondered what else he was capable of. They wondered what they would see him do today.

He flew for two minutes and he exalted, as he always did, at the feeling of flying. He trembled and thrilled, as any of his contemporaneous pilots did, at the perversity of being a being out of its element, a large land mammal zipping through the air like a gull. He must have known, too, that one wrong move and it could all be over.

But it wasn't his move that did it. It was a gust of wind.

Suddenly, he lost control. He pitched into a rocky ravine. His last words, according to those present (although who could have been able to hear it over the sound of his propellors, the wind, the gasps of the crowd?), were "Here I go!" Flight ceased; Dixon came back to earth.

Dixon was buried in Columbus, Ohio.

The next month in Macon, Georgia, Dixon's contemporary Eugene Ely, his own place in history secure and after eight consecutive days of exhibition flights, promised those present a demonstration of a highly dangerous move called the "spiral dip." He failed to complete it and the plane fell into a dive. He jumped at the last second, but it wasn't enough to save him.

Amelia Earhart, herself a tragic victim of a love of flying, once said, "You haven't seen a tree until you've seen its shadow from the sky."

Today, thousands of people sail right over Montana in jumbo jets, much too high to be able to discern anything so small as the shadow of a tree.

By Earhart's metric, most folks haven't really seen any of Montana's trees. But Dixon, Ely, and their ilk did. They saw Montana's trees cresting her mountains, straddling her Divide, casting long shadows on places on which no foot had ever landed.

Each of them had their shining moment when, Icarus-like, they had hung in the sky.

Leave a Comment Here