The Stench of the Frontier

Personal Hygiene in the Old West

In 1890, a man in the Yukon Territory won a bet thanks to a pile of dead horses. As Jeremy Agnew details in Medicine in the Old West: A History, 1850-1900, one Arthur Walden bet his friends that he could cross the unpaved main street in the gold rush town of Dawson without muddying his shoes. Much to the chagrin of those who bet against him, Walden hopped from one horse carcass to the next all the way across, winning his unlikely wager with ease and grace.

Walden would probably have won his bet in any number of Western towns. Dawson’s refuse-strewn thoroughfares were the rule rather than the exception in the Old West. Basic sanitation infrastructure like running water and closed sewer systems were becoming more commonplace in many East Coast metropolises by the middle of the nineteenth century, but such lavish advancements were still years off for the rough-and-tumble specimens who made their home in the rugged Rockies, the vast plains, and any number of grimy, godforsaken corners on the American frontier.

Add to this the lack of hygiene products that we take for granted today, and the texture of the situation really starts to come into focus. Colgate wouldn’t invent toothpaste until 1873. People instead used tooth powder, baking soda, salt, or campfire ash. Deodorant wasn’t mass produced until 1888, and soap consisted of a musky mix of ash and animal fat. Toilet paper didn’t make an appearance until 1880; at best, people used leaves, dry corn cobs, or pages torn from The Farmer’s Almanac.

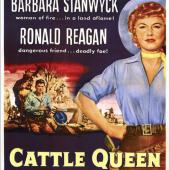

If Manifest Destiny had a smell, it would surely stink of rotting garbage, excrement, and a heady whiff of BO. Literature and film have cultivated in the American imagination a highly romanticized take on the Old West, but they’ve necessarily left out some of the crustier details of day-to-day hygiene.

MORE PRECIOUS THAN GOLD

The biggest obstacle to personal hygiene in the Old West was limited access to clean water. Arid climates exacerbated the problem. Once dependable water sources could go dry or stagnant, and even if running water were nearby, it was likely that an upstream outhouse would pollute it. Potable water was a precious resource, and people conserved what little they had by not washing dishes, clothes, or their own bodies.

Much in the way that a good cast iron must be seasoned to last, citizens self-seasoned in the name of convenience and survival. Take for example the parents who sewed their children into their clothes for the winter. Family physician Arthur Hertzler notes in his memoir The Horse and Buggy Doctor, “All the boys were sewed into their clothes in the fall when cold weather approached... They woke in the morning all dressed... In the spring, the clothes were ripped off and the child saw himself for the first time in a number of months.”

Bathing in the home was a family event. Water had to be carried from the source bucket by bucket, heated on the stovetop, and poured into a small tub. Father would wash first, followed by mother, followed by each child in order of age, all in the same water. The general unpleasantness and inconvenience of the chore goes a long way to explain why people didn’t do it often.

Sponge baths were more the norm for both men and women. While men could strip wherever they pleased and bathe in a creek if it were available, women did not have the tacit permission to do the same in a society governed by rather prudish quasi-Victorian mores. Women took their sponge baths indoors, usually wearing their long, heavy undergarments because of the lack of privacy. This turned their sponge bath into more of a token gesture at cleanliness than anything else.

Conveniently for them, it was believed that bathing too often would open the pores and invite in even more disease. That being said, people were not dirty and smelly for lack of trying—their workarounds were quite inventive, though usually not very effective. If anything, their personal hygiene hacks often made things a whole lot worse.

BAD HAIR DAYS

Washing one’s hair was low priority, given how much hard work it was to get clean water. People favored regular brushing over washing. The old rule of brushing the hair for one hundred strokes before bedtime is attributed to the Victorian era. When hair did get washed, it was usually not with water, but with whiskey, castor oil, or vinegar—possibly egg yolks if you were well-heeled and could afford to waste good food on your appearance.

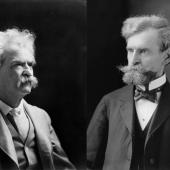

In his autobiographical travelogue Roughing It published in 1872, Mark Twain describes the vile and possibly counterproductive personal hygiene services offered at a stagecoach station in some desolate corner of the Far West. Twain notes the tin washbasin, pail of water, and yellow bar soap sitting on the hard-packed ground. Water, soap, and basin were all communal, shared between the station-keeper, half a dozen stablemen, and every traveler who passed through and cared to partake.

Twain describes with disgusted amusement another communal implement attached to the mirror: “From the glass frame hung the half of a comb by a string [...] it had come down from Esau and Samson, and had been accumulating hair ever since—along with certain impurities.” The precise nature of these impurities Twain leaves to the reader’s imagination, but one might guess some were likely crawling around the comb teeth on their own. So much for staying clean on the road.

Both men and women sported long locks as a general rule up until the Civil War, when shorter styles for men came into vogue. While hairstyles came and went, facial hair remained the norm for men throughout the 19th century. From mutton chops to the Van Dyke, men had no shortage of options.

What’s more, a full beard was recommended by Victorian-era doctors as a way to stave off disease, the logic being that it acted as a sort of air filter. Never mind that beards obviously house more bacteria and bits of food than they keep out. Saloon patrons would use a shared towel to wipe their beards off after imbibing, compounding the problem. But given the Victorian preoccupation with air purity, the filter theory makes some kind of sense. The problem was that people were concerned with air quality for all the wrong reasons.

MIASMAS, THUNDERMUGS, AND THE SPREAD OF DISEASE

19th century folks had a vague understanding that unclean water and impure air made for an unhealthy living environment. They were on the right track, but had not wholly arrived. Clearing the streets of garbage, excrement, and dead animals had the effect of eliminating the real sources of infection, but an understanding of bacteria and viruses was next to nonexistent. Although Louis Pasteur’s germ theory was slowly gaining traction in the medical community, many doctors out West still believed that miasmas were the cause of infections. The miasma theory held that diseases like cholera, smallpox, and dysentery were transmitted not from person to person, but through the air by foul-smelling vapors.

To the good folks on the frontier, the link between disease and hygiene remained a mystery for a long time. When outhouse pits would fill to capacity, the hole would be covered with a layer of dirt, a fresh pit dug a few feet off, and the entire outhouse picked up and dropped over the new hole. Chamber pots, or “thundermugs” as they were affectionately called, were emptied out the window every morning. Flies would come inside and land on the dinner table; that they were vectors of disease was not immediately apparent. It was only when people started adding lime to outhouse pits and noticed the white trails that flies left behind on their food that the connection became clear.

Conditions were dire in saloons as well. In an effort to keep things clean, sawdust was spread on the floor to soak up poorly aimed wads of tobacco. Newcomers to town could rent a space to sleep on the saloon floor for twenty-five cents a night. Sleeping on a bed of tobacco-drenched sawdust all but guaranteed these poor souls a case of pneumonia or tuberculosis.

THE LEGACY OF POOR HYGIENE

Not everyone in the Old West was disgusting. In fact, the farther you found yourself from town, the better chance you had of maintaining a level of cleanliness that approached acceptability by modern standards. Most Native Americans had it down pat, camping near water sources whenever possible—lakes, rivers, hot springs—so that bathing was easy and routine. A varied diet of fresh meat, roots, and berries helped maintain digestive health and largely avoid the diarrhea, constipation, and dysentery that plagued the average miner or soldier who subsisted on hardtack and booze. Additionally, nomadic tribes moved to new camps often enough that accumulated trash and human waste rarely proved to be the health hazard it was in town.

A lot can be learned about the character of a nation from its past, but only when the past is acknowledged as a whole rather than cherry-picked for its most attractive parts. Thankfully, in terms of personal hygiene we have come a long way. All the same, perhaps future generations will look back at us and lament our abysmal hygiene habits. Only time will tell.

Lindsay Tran is a freelance copywriter living and working in Helena. Originally from Bozeman, her writing and research interests include history, health and wellness, and contemporary American literature. She enjoys gardening, hiking, reading, and horror movies.

Leave a Comment Here

Also growing up in the forties, I remember the men moving the outhouse, the iceman, ragman, junkman, and others who patrolled the neighborhoods. The icebox, rug beaters, coal stoves, and cold-water sinks. Bathing on Saturday nights behind the stove, in a small galvanized tub, in the order you mentioned. Using toothpowder, castor oil, mercurochrome, playing with the mercury from thermometers, and chewing on lead paint. The only difference is that I lived in the coalfields of Northeastern Pennsylvania.

- Reply

Permalink