Montana's Copper Press

The year was 1897, and 29-year-old Joseph Burns cut to the point as he introduced himself and his newspaper, the weekly Knocker, to the solid citizens of Belt, Montana.

Libel suits would be laughed off, he wrote, and offended readers would find it hard do him harm, “as I am something of a foot racer.”

In politics, Burns promised his paper would wear “no man’s collar,” though he confessed he liked the sound of the Democrats’ latest creed: the “free coinage of silver,” a popular if dubious monetary scheme that even supporters found hard to explain.

But Burns knew exactly what it meant. “Free silver will be the watchword,” he wrote, “and the freer it is showered upon your humble servant the better he will like it.”

Transported back in time, no modern news junkie could fail to notice the colorful and combustible mix of journalism and politics that bled through the scores of news “sheets” that sprouted across Montana more than a century ago.

No community of serious ambition boasted fewer than two newspapers, each manned by “quill drivers” who boosted their towns, industries, and political factions in a slashing partisan style that exists today only in the blogs. Fair and accurate? Forget about it.

The editor of Virginia City’s Madisonian was only doing his job when he described one 1876 issue of Bozeman’s weekly Chronicle as filled with the “usual amount of deplorable vulgarity.” Slinging ink was art, though few could match the stylish vehemence of Helena Herald editor, Robert Fisk, who once compared the rival Rocky Mountain Gazette to the “gorged condor of South America” that “vomits the disgusting contents of its stomach in the faces of its several readers, in a manner which is enough to sicken a dog.”

Many Montana editors subscribed to the motto “independent, but never neutral,” and politics was the lifeblood of early journalism. It was business, too. In a time of open spoilsmanship, smart politics could lead to government printing contracts or employment.

Pioneer editors saw no conflict in holding public office as they molded public opinion. “Captain” James Hamilton Mills, the father of early newspaper ventures in Virginia City, Helena, Anaconda, Butte and Deer Lodge, supplemented his editorial duties by serving variously as Montana’s territorial secretary; adjutant general of the militia; collector of federal revenues; state commissioner of agriculture, labor and industry; and Powell County’s first clerk and recorder.

That intertwining of politics and press would have serious consequences as big money poured into Montana in the years leading to statehood in 1889. By the mid-1890s, major industrialists owned or controlled several leading dailies. The copper king, W.A. Clark, about to embark on his scandalous campaign to buy a U.S. Senate seat, controlled the Butte Daily Miner. A.B. Hammond, timber tycoon and mercantilist, owned the Missoulian. Railroaders and bankers had their Billings Gazette.

But in 1889 Marcus Daly, the mining genius behind the Anaconda mining company, outdid them all in creating the magnificent Anaconda Standard. For a generation, the Standard sparkled as not only Montana’s best daily newspaper, but one of the best in the region. One rival quipped that of the first $16 million in treasure Daly’s miners pulled from the ground, half went to the Standard. “The only time the paper made a profit was when the business manager forgot to pay the staff,” he added

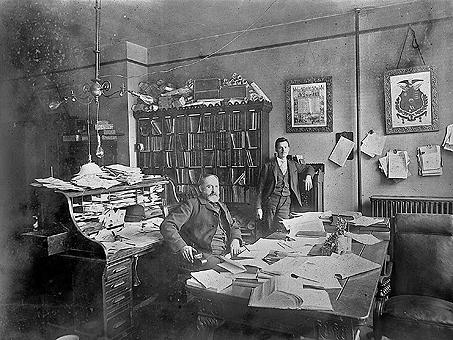

Stocked with the latest technology and staffed with talented editors, reporters, and artists, the Standard offered the timeliest news and features available, fare newspapers readers of the day could only find, as one contemporary wrote, in “the New York Journal or other millionaire metropolitan sheets.” Beyond Montana, the Standard also landed on newsstands in San Francisco, Chicago, and New York. One apocryphal tale reported a traveler’s delight in finding the paper on the streets of Singapore.

Daly’s money paid for it, but the responsibility for raising the Standard fell to John Hurst Durston, a former professor and New York newspaperman with an undergraduate degree from Yale and a doctorate in language and literature from the University of Heidelberg.

Hot-tempered but shrewd, Durston directed the Standard with bombast and enthusiasm. When a nationwide rail strike blocked the paper’s distribution, Durston organized relays of hand- and pedal-powered rail carts to haul papers west to Missoula and eastward, over the Divide, to Livingston. From there, horsemen took papers as far as Mammoth Hot Springs, where stranded vacationers snatched them up.

Above all, the dailies owned by Clark and Daly were political weapons, and their first statewide battle erupted over the contest between Daly’s smelter city of Anaconda and Helena, Clark’s favorite, to host Montana’s capital. Ink flowed, along with the whiskey, cigars, and cash. Clark’s Miner and Helena’s dailies, the Independent and Herald, stuffed their news and editorial columns with warnings against placing state government within the grasp of Montana’s “white czar” and “boss Irishman.”

The Standard fired back. Helena, the “Hogopolis” and home of millionaires, cared little for the average working stiff, wrote Charles Eggleston, the Standard’s deputy editor and a leader of Daly’s faction in the Legislature. “There are people in Helena who can trace their ancestry back two or three generations without discovering a single flaw in the form of a day’s work or a night’s sobriety,” he wrote. When Helena won, its residents celebrated by pulling a decorated carriage up Last Chance Gulch to the cheers of thousands. Seated inside with Clark was the editor of his newspaper.

Montana’s newspaper battles peaked during the so-called “War of the Copper Kings,” a five-year political slugfest whose first rounds featured Clark’s drive to the U.S. Senate and Daly’s efforts to stop it. Standard writers howled at Clark’s flagrant bribery of state legislators who elected U.S. senators back then. Meanwhile, the paper’s cartoonists created enduring images of “Boodler” Clark, the “man-buyer.”

Faced with evidence of graft on both sides, a committee of U.S. senators recommended Clark’s expulsion (he quit before they could kick him out), but the investigation offered another revelation: The big money that had stained Montana’s politics had corrupted its press as well.

Paper after paper, weeklies and dailies alike, succumbed to the lure of subsidies, buyouts, or offers they dared not refuse. Faced with Clark’s threat to start a competing daily, the pro-Daly owners of the Great Falls Tribune sold out. The pro-Clark editors of Bozeman’s Chronicle faced a similar choice before selling out to Daly. When the Helena Independent, secretly on Clark’s payroll, criticized Daly’s newspaper buying, the editor of Big Timber’s weekly Express replied that at least Daly paid “good, honest prices.”

Nobody knows how many Montana newspapers were bought or commandeered during the period, but the phenomenon continued after Clark’s next and ultimately successful Senate campaign and Daly’s death in November 1900. The Anaconda Company’s purchase by speculators with Standard Oil connections only fueled the trend.

Contemporary estimates put the newly christened Amalgamated Copper Company’s newspaper investment at $1.5 million, an enormous sum for the time. That would grow as the company trained its presses against a third copper king, F.A. Heinze, an audacious operator who skillfully attacked the company’s ownership of mines in Butte’s sympathetic courts.

By 1904, Robert Sutherlin, editor of the state’s most respected farm weekly, the Rocky Mountain Husbandman, moaned that independent journalism had been “ruined as a legitimate pursuit.” Of Montana’s 100 papers, he doubted “there are as many as a baker’s dozen that dare to give expression to their honest sentiments.”

Though outnumbered, Heinze’s newspapers, the weekly Reveille and daily Butte Evening News, could sling ink with the best of them. The papers’ cartoons, the equivalent of today’s TV “attack ads,” were masterpieces of exaggeration and invective. Their theme—that Montana was becoming a corporate colony–—struck a chord that would ring for decades. So too would the company’s legacy of press control.

Heinze’s sellout in 1906 ended the copper wars, and in their wake Montana experienced a small flowering of reform, a reaction to all the corruption and coercion. Progressive farm-country editors like Miles Romney of Hamilton’s Western News and William Harber of Fort Benton’s River Press pushed for the initiative and referendum, the direct primary, and the popular election of U.S. senators. A small but feisty Socialist press helped win fleeting victories for municipal reforms in Butte and elsewhere.

But the company and its allies remained powerful players in Montana’s press and politics. By World War I, the Anaconda Copper Mining Co., as it was once again known, and its now ally Clark owned three of Butte’s four dailies—all but the radical and short-lived Butte Daily Bulletin. With allied editors at the helms of dailies in Missoula, Helena and Billings, the “copper press” hounded radicals, unionists and those it labeled “anti-American.” It promoted passage of Montana’s draconian sedition law and urged the suppression of publications deemed “unpatriotic.”

Yet its influence had limits. It failed to derail the election of progressive Joseph Dixon as governor in 1920. Though it helped drive Dixon from office four years later, it failed to prevent voters’ approval of Dixon’s chief legislative priority: an increase in mining taxes.

It was time to change tactics. Over the next six years, the ACM formally acquired dailies in Missoula, Helena and Billings. In 1928, it fought off a weak effort to establish competing dailies in Missoula, Butte and Billings. By 1930, only Great Falls could boast a major daily that wasn’t under the company’s thumb.

Readers noticed other changes, too. Gone were the colorful slashing attacks of the copper wars. News suppression and self-censorship now ensured that controversies involving the company and its friends either never made the news or were grossly underplayed. Miners’ deaths were ignored, along with miners’ illness such as silicosis and their side of labor disputes.

Campaigns of anti-company candidates went all but unnoticed. Coverage of the state’s crucial Legislative sessions were relegated to carefully vetted Associated Press stories; company lobbyists held press passes giving them access to the floor of the state Senate and House. Editorials extolled Montana’s natural wonders or the politics of faraway places, avoiding any local subject more controversial than “the need for shade trees on Main Street,” as one editor put it.

One study of editorials appearing over the last years of Anaconda journalism found that less than 3 percent pertained to state matters; local subjects accounted less than half a percent.

The real mystery of Montana’s “copper-collared” press is that it lasted so long.

Industrialists elsewhere had used their power to control the press, but by the late 1940s, with advances in broadcasting and in the modern art public relations, such tactics had become grossly outdated. Montanans who traveled could not help but see the timidity of their own state’s press and its lack of credibility. Outside observers could only describe it as an embarrassment, an anachronism in the age of jet planes and the Cold War.

The international magazine, The Economist, guessed that Montanans must be the worst informed citizens in America. Author, John Gunther, who toured the state after World War II, found much to admire but could only shake his head at the copper press. “Why the company thinks such an antediluvian tactic as ownership of its own newspapers is a good idea remains a mystery to most experts in public opinion,” he wrote.

The company finally reached that conclusion in 1958, after the death of its last great chairman, Cornelius “Con” Kelley, who had known Marcus Daly himself. After a nationwide search, Anaconda’s newspaper division accepted a buyout by a syndicate of Midwestern newspapers that would later become Lee Enterprises.

The physical legacy of Anaconda journalism is Lee’s clustered ownership of five Montana dailies, but beyond that comparison has little to offer. News has long since replaced views as the priority, and a corporate commitment to local autonomy usually ensures editorial independence.

Today’s challenge for newspapers is to hold onto readers as they migrate to the Internet; yet the lesson of Anaconda journalism still may prove useful as the giants of the Information Age, the Googles, and Yahoos, add news to their vast array of services.

Montanans know all too well what happens when the news becomes just a sideline

~ Dennis Swibold is a professor at the University of Montana’s School of Journalism. He is a former editor of Bozeman Daily Chronicle and the Sidney Herald. His book, Copper Chorus: Mining, Politics, and the Montana Press, 1889-1959, published last year by the Montana Historical Society Press, won the Western Writers of America’s 2007 Spur Award as the best work of contemporary nonfiction. He lives in Missoula with his wife, Julie, and son, Colton.

Leave a Comment Here

Leave a Comment Here