Evelyn Cameron, Forever

In 2007, a Chicago woman was unable to keep up with payments on a storage unit, so the contents of the unit were auctioned off to several collectors. One of these collectors, John Maloof, discovered several thousand photographic negatives among his haul, and when he started publishing these photographs, they began to garner attention from art critics.

By the time Maloof discovered the name of the photographer on one of the boxes, and tried to track her down, Vivian Maier had died, in 2009. But Maloof made a concerted effort to acquire as much of her work as he could find, and now owns about 90% of Maier’s work, which includes around 150,000 negatives.

But the more Maloof researched Maier’s own story, the more fascinating it became. It turned out that Vivian Maier had worked for decades as a nanny in New York City, taking photographs, mostly on the streets of New York, as a hobby. Her collection has since become known as one of the most accomplished and extensive urban exposés in the country.

When I heard this story a few years ago, I was immediately reminded of a similar story here in Montana. For decades, there were rumors, especially among the museum community, about a woman in Terry named Janet Williams, who had a collection of glass plate negatives from a photographer who lived in that part of the state in the late 19th and early 20th century. Nobody knew for sure exactly how much material Williams had, but in 1978, a writer from Virginia named Donna Lucey, who was working on a project that included photos from the Great Plains region, tracked down Janet Williams to try to convince her to share what she had.

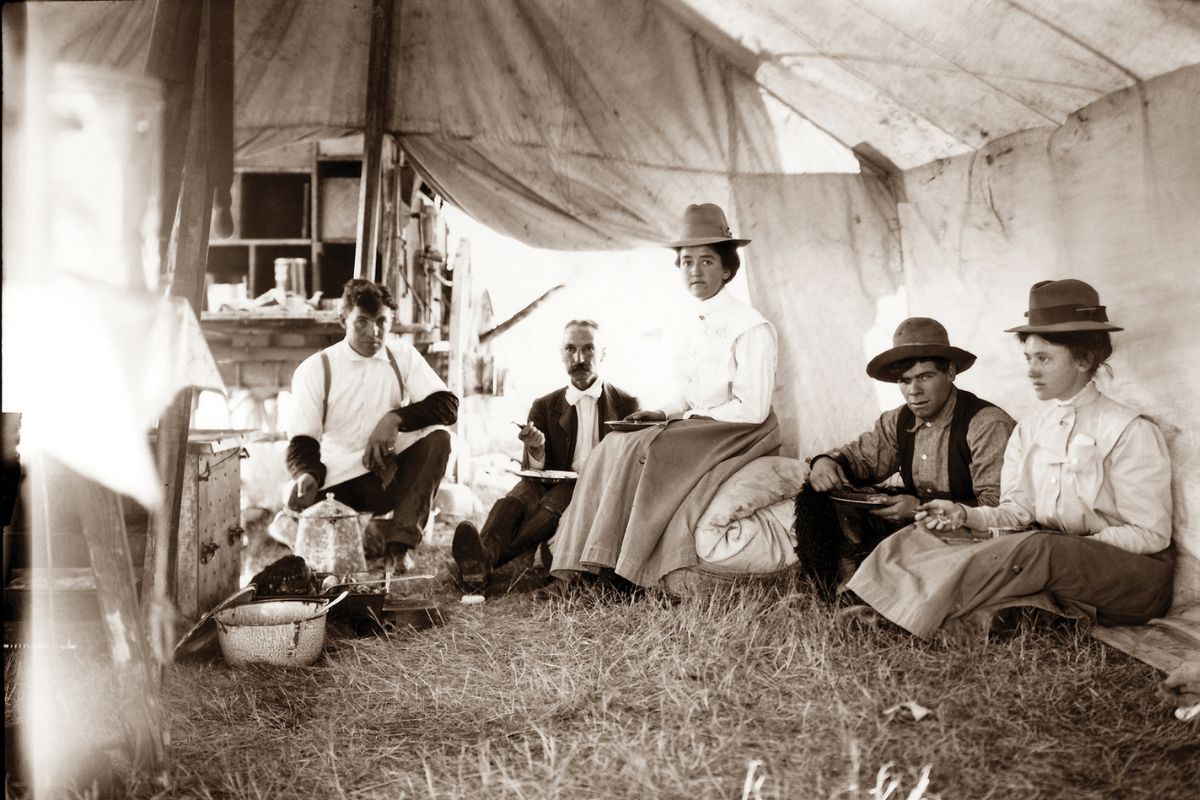

Lucey spent months communicating with Williams by mail, and when Williams sent her a handful of prints, Lucey quickly recognized the quality of the work, and convinced Williams to allow her to come for a visit. When Lucey arrived in Terry, the ninety-five-year-old Williams greeted her at the train with her niece and took her home. It took Lucey several days to earn Williams’ trust enough to give her a peek at what was in her basement. It turned out to be a treasure that has since brought the photographer, a British transplant named Evelyn Cameron, international recognition in the world of photography. Lucey found over a hundred boxes filled with glass plate negatives, film, and to top it all off, a daily diary from every year Evelyn Cameron lived on the Eve Ranch, from 1894 to 1928.

But the main thing that struck Lucey right away was the stunning quality of Cameron’s photography. In an era where most photographs showed their subjects as stiff and unsmiling, Cameron captured life on the prairie with a realism that was unique. She also had an eye for nature that was entirely her own, and as Lucey would later discover, often spent hours perched in complete stillness in order to capture a photo of a bird landing in its nest. At a time when there were no telephoto lenses, Cameron managed to get some incredible closeups of birds and other animals because of this patient determination.

Unlike Vivian Maier, Evelyn Cameron came from money. A lot of money. Her father was a successful merchant, and one of her half-brothers was member of the British cabinet under Gladstone, while her mother was a descendant of the Rothschild family. But when Evelyn met and married an eccentric gentleman named Ewen Cameron, who was about fifteen years her senior, they chose to visit America for their honeymoon. Only they didn’t choose the nightlife of New York City. Ewen was obsessed with nature, particularly ornithology, and Evelyn shared his fascination with wildlife, so they traveled to the prairie of eastern Montana. Lucey speculates that their choice may have been influenced by the fact that Evelyn’s family didn’t approve of her choice for a husband, who was clearly below their station in the world. And although Cameron was given a monthly stipend from her family’s fortune, it didn’t amount to much, and her family consistently refused to help her even in some of her more desperate years. So her choice ended up costing her a great deal financially, although there is little indication that she regretted that decision.

Ewen proved to be much more blessed at coming up with ideas than he was with business sense. So for the decades they lived in eastern Montana, it was usually Evelyn who kept them financially viable, with little help from her husband.

What became more apparent to Lucey as she worked her way through the years of diaries was that Evelyn Cameron was not your typical British aristocrat. She fell in love with the rigorous life of the prairie, and unlike many of the aristocracy who lived and wrote about their time in the West, Cameron didn’t have a pretentious bone in her body. She loved doing physical labor, and would accompany Ewen on weeks-long hunting trips every fall, sleeping in a tent, gathering meat for the winter. Cameron became very popular among the locals for her willingness to help with anything and everything. And eventually, she became the only choice for anyone who wanted a photographic record of any event in the region.

I have to wonder whether both Cameron’s and Maier’s work would have been taken more seriously if they were men. The fact that they weren’t recognized for the quality of their work during their lifetimes, especially considering that Cameron’s photographs compare favorably with the contemporary men such as A.D. Huffman, doesn’t make sense. Even Huffman was a fan of her work, buying several prints from her.

The one thing they did have in common was they both liked to capture snapshots of lives in action. Although Cameron was happy to do portraits if people requested them, she mostly did that for money, and did not enjoy it, especially if there were children involved. Her real gift came out when she was capturing authentic life in the West. People harvesting. Or doing household chores. Or gathering for parties. There is a lot of laughter in her photographs.

Part of the reason Cameron had such a fabulous eye for the everyday details of life on the prairie could have been because she didn’t grow up in that environment. You can tell from her diaries that even though she and Ewen were always facing enormous financial difficulties, she never lost that sense of adventure and love for the work that she had when she first arrived.

And the financial difficulties were almost comical in their persistence. On top of Ewen having such a bad head for business, he was perpetually unlucky. Ewen’s biggest dream was a business raising polo ponies, which was probably just as goofy as it sounds in a place where people didn’t play polo. But several times, he managed to make arrangements with buyers overseas. Each time, something tragic seemed to happen. Once Ewen fell off one of the horses while delivering them to be shipped, causing a severe concussion that might have contributed to his death decades later.

On his final delivery, Ewen shipped eighteen horses, which he met in London, only to find that they had not been fed properly. Six of the eighteen died either on the way or soon after. Also, although the buyer was pleased with the quality of the remaining horses, the fact that they had been raised in such open country made them almost impossible to train for a disciplined sport like polo. So Ewen had to pay for several months’ worth of training.

They lost a lot of money on the deal, which brought a sad end to their pony business. Even more sadly, the next year Ewen bought a herd of cattle, only to have the horse market explode due to the Boer Wars. And in another stroke of bad luck, an epidemic of black leg spread through the region, infecting their cattle, forcing the Camerons to return to England for one miserable year.

Evelyn faced another burden during most of their time out West, which was the presence of her shiftless brother Alec, who moved in with them and provided nothing but trouble. Although the family paid them a small stipend to help support Alec, he rarely contributed to the welfare of the ranch, and worst of all, when they brought several prospective business partners to the ranch, Alec became impossibly rude and even abusive toward these men, chasing them off before they made any financial commitment.

Through it all, Evelyn produced, somehow carving a small darkroom out of their three-room shack in the middle of nowhere. She produced an incredible catalogue of photography while at the same time running the ranch, with almost no help from Ewen, raising vegetables and chickens for eggs to make extra money, and doing all of the housekeeping.

The love story of Evelyn and Ewen is kind of remarkable, because despite the fact that Ewen took advantage of her work ethic, always living in a world where he thought he would somehow become recognized for his writings about birds, she still adored him right up until he died in 1915.

One of the more telling incidents involved Ewen’s fastidious nature about his appearance. Apparently, while Evelyn was up early every morning gathering eggs, milking the cows, and preparing breakfast, Ewen would rise at his leisure, and then take his sweet time getting ready, including trimming his handlebar mustache. One morning, after Evelyn had prepared another huge breakfast, Ewen came out late as usual, sat down, discovered a fly in the cream, and threw the cream on the floor. Evelyn fled the room in tears.

Evelyn lived another thirteen years after Ewen’s passing, and when she died, the funeral attracted a massive crowd of admirers, telling stories about how she contributed to the community. And although her photography was greatly appreciated by the locals, none of them, including Evelyn herself, had any notion that she would someday become internationally renowned for her gifts.

- Reply

Permalink