Starring John Wayne: Identity and Reinvention on the Big Trail

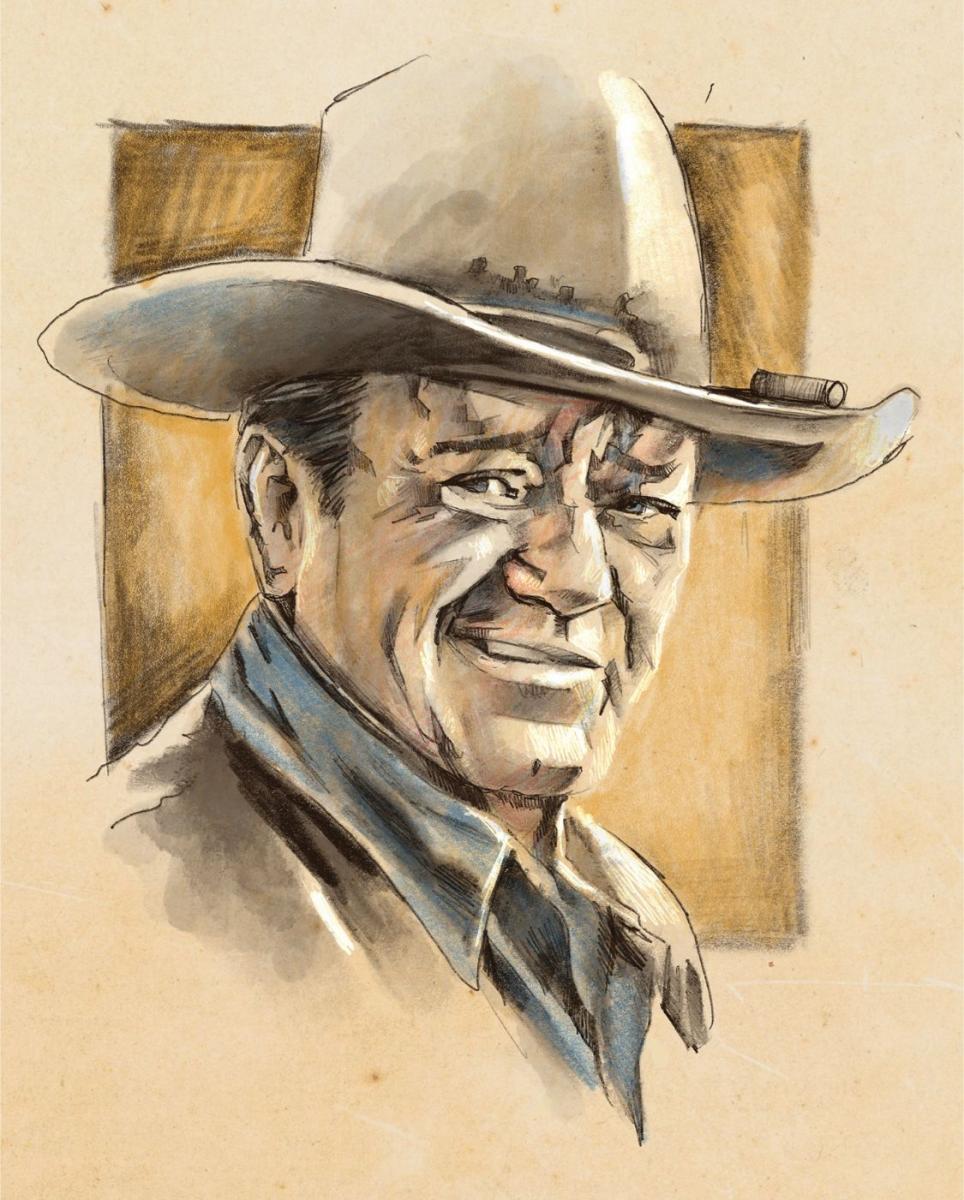

The director Raoul Walsh, best known today for the 1949 Jimmy Cagney-starring gangster flick White Heat, was something of a cowboy himself. At fifteen, after his mother died, he set off across Texas, eventually made it to Montana, and later became a working cowboy in Mexico. He made his film debut (as an actor rather than a director) in 1915's The Birth of a Nation, in which he embodied the role of John Wilkes Booth. He starred opposite the actual Pancho Villa in The Life of General Villa.

Later, while filming an adaptation of an O. Henry Western, he lost his eye after a jackrabbit went through the window of his car.

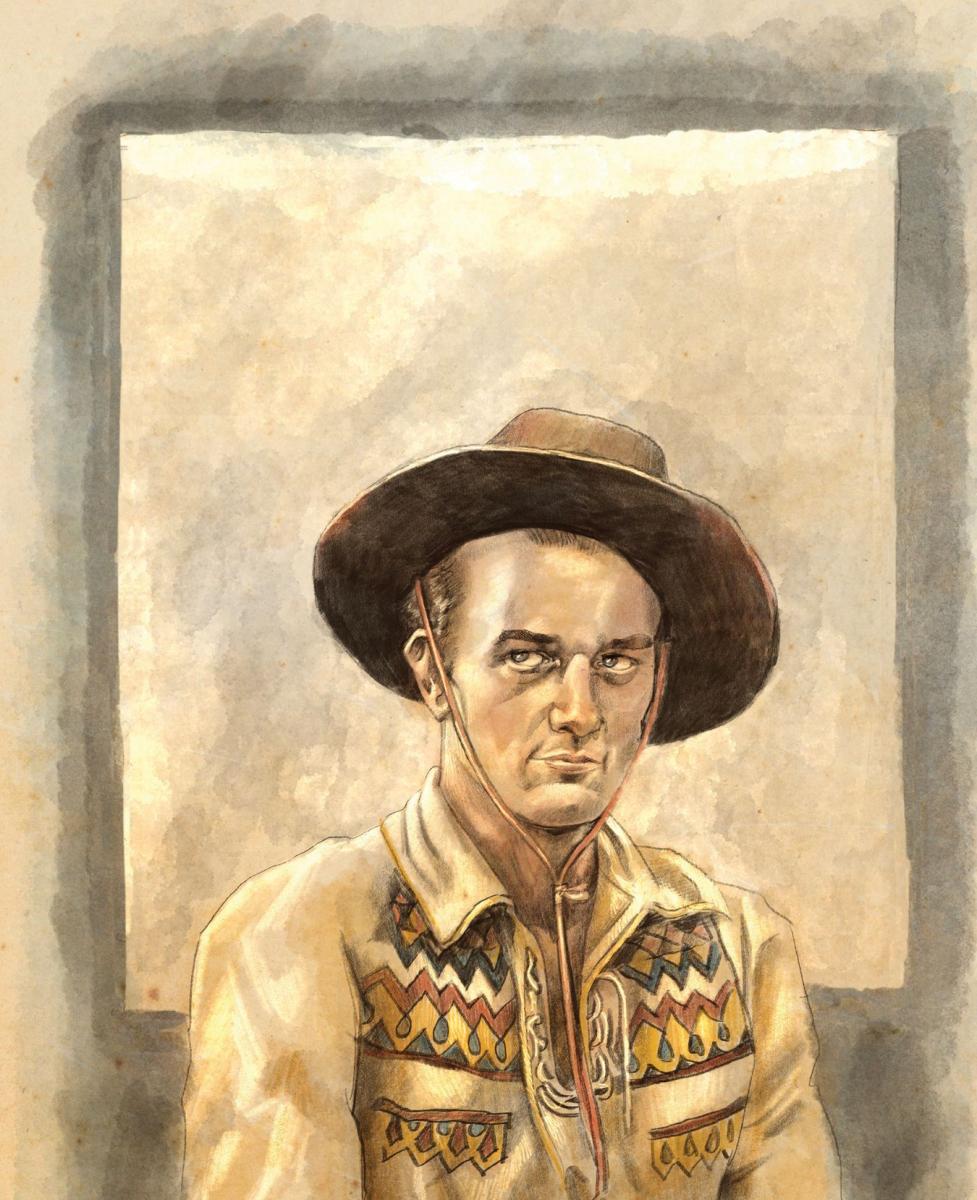

His 1930 film, The Big Trail, called for a good-looking, clean-cut young cowboy for the role of Breck Coleman, a trapper and guide guiding a large caravan of settlers along the Oregon Trail while also searching for the villains who killed his friend. Above all, the role called for the mix of bravado, virtue, and vulnerability that would, and still does, define the Western hero in film.

Gary Cooper was the first choice, but as Walsh wrote in Each Man In His Time, his autobiography, "there were not many Coopers and Gables around, it seemed."

The Helena-born movie star, known for a leading-man visage that seemed carved from granite, was too busy. So too were Clark Gable, and Tom Mix.

In the 27 years after The Great Train Robbery, which wasn't even the first Western, there had been nearly 1,000 Western films made. Most of those were silents, but in 1928, sound had been introduced to the movies. Cooper himself had starred in two Western "talkies" already, the partly sound, partly silent Wolf Song, and the classic Owen Wister adaptation The Virginian.

With all due respect to those films, The Big Trail was going to be something else entirely: an American spectacle to rival and surpass anything that Buffalo Bill had ever staged, and wired for sound. The film crew, along with the hundreds of extras, would for all intents and purposes have to travel the actual Oregon Trail, enduring real dangers and inconveniences, inconstant weather, and the human irritations that come with traveling in a group. In short, they'd have to become real pioneers, at least for a time. And, for the stars of the picture at least, they'd have to look earnest and determined—and don't forget, sexy, too. But what magic produces a leading man out of thin air?

Walsh’s problem was serendipitously solved when he happened to see a lanky youth hauling furniture in and out of the prop department on the Fox lot.

Walsh adjusted his eye patch and watched the man, whose name, he would learn later, was Marion Robert Morrison. Walsh would remember the moment he saw the "tall young fellow" with "wide shoulders to go with his height." He was good-looking enough, certainly.

"He was unlaoding a truck and did not see me," he wrote. "I watched him juggle a solid Louis Quinze sofa as though it was made of feathers and pick up another chair with his free hand."

Walsh got his attention and waved him over. He asked the prop department man his name, and what he wanted to do. Morrison said he'd like to star in movies but hadn't had much success yet. He said he could play football pretty good and had done so at the University of Southern California with some success.

Walsh "liked the tone of his voice and the way he carried himself. He was big, but he moved easily."

Walsh decided to let him test for the starring role in his next picture, the ultra-ambitious Western.

But Winfield Sheehan, a big-wig producer at Fox, was skeptical. Walsh writes that when he introduced Morrison to Sheehan, the executive responded, "Who is this guy? Can he ride a horse? Where the hell did you find him?"

And then there was the biggest question of all, the one which had already ruined careers in the rush from the silents to sound (see Singing in the Rain): "Can he talk?"

He could, or at least he showed potential. Walsh said, "For a college man, he read well enough, but he fell into the common trap of beginners. He overdramatized his lines."

Walsh had some advice for him:

"You've traded yourself in for a Western scout, a plainsman. So play him with a cool hand like I think you'd do on a football field. Speak softly but with authority, and look whoever you're talking to right in the eye."

In following Walsh's advice, Morrison would adopt a persona that would serve him for the rest of his life, in films like Stagecoach, The Searchers, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and True Grit. It was a screen presence the sheer magnetism of which made him one of the most recognizable figures in the cinema and assured him entry into movie-star Valhalla.

But there was still the issue of his name. Walsh had been reading a book about the soldier and founding father "Mad" Anthony Wayne and the name had stuck with him. He suggested it to Sheehan, who "looked up and smirked as though he had thought of it," Walsh reported.

"He grabbed the pencil again, then read what he had written. 'Wayne. Not Mad Anthony, just John will do.’"

Looking back from a perspective 45 years later in 1975, the actor, now world-famous and widely regarded as one of the great movie stars of all time, would muse that the transition from his given name to his screen persona was sometimes difficult. "It took me a long time. I've never really become accustomed to the John. Nobody ever really calls me John... I've always been Duke, or Marion, or John Wayne. It's a name that goes well together and it's like one word -- JohnWayne. But if they say John, Christ, I don't look around today."

The production of The Big Trail waffled between troubled and sublime. According to Walsh biographer Marilyn Ann Moss, "20,000 extras, 1,800 head of cattle, 1,400 horses" traveled with the production, along with "185 wagons" and "123 baggage trains that trekked over 4,300 miles in the seven states used for locations." Finally, there were 293 actors, 22 cameramen, and 700 barnyard animals. It was a four-month shoot, from April to August of 1930.

Wayne was to star opposite leading lady and screen beauty Marguerite Churchill, who had enjoyed success in films like Born Reckless, Pleasure Crazed, and The Valiant. Walsh suggestively says that Churchill "decided she liked him. Too much personal involvement between leading characters can go two ways... But I had no fears on that score. My female lead looked stunning in a sunbonnet, but young Wayne's full attention seemed to be concentrated on the part he was to play."

The studio had been nervous that the newcomer John Wayne, gifted as he was with charisma, would be able to carry a picture of this size. One film publication called him "an actor whose only experience had been in bits, extra work, and assisting the Fox prop shop." And, as Moss reports, "[a] writer for the Hollywood Filmograph noted: 'Just how he [Walsh] can expect a youth to carry such a picture is beyond my conception. If he brings in a winner with Mr. Wayne he will be entitled to a Carnegie medal.’" The studio felt that the solution was to bring experienced New York theater actors to round out the supporting roles, sure that their steady hand would lead to a smooth production.

Instead, the greybeards of the New York theater scene, who included Tyrone Power Sr., Ian Keith, and Broadway comedian El Brendel, spent most of the shoot inebriated.

"With their appearance," Walsh wrote, "the name of the picture should have become The Big Drunk. This part of the cast probably scattered more empty whiskey bottles over the Western plains than all the pioneers."

As the shoot wore on, the booze flowed freely. The hardships of the road and trail wore on what Walsh called "the New York contingent, who complained that such mishaps interfered with their drinking. When I turned down their requests to bring more women along, I believe they would have quit in a bunch except that there was no place to go... As it was, the night stops were turning into orgies."

The complicated and well-liquored shoot had wended across the American West like a crazy quilt; from Yuma, the production followed the Colorado River, then back to Sacramento, then onward to Utah, back to the Sierra mountains of California and north. The end of the shoot was to be in Moiese, Montana, where a climactic buffalo stampede would be filmed using the herd collected on what was then the National Wildlife Reserve, now the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribe Bison Range. As Walsh writes, "Washington had given Fox permission to use the herd providing no hardship was inflicted on the animals."

"Moiese was the next stop," Walsh remembered. "As soon as I had the buffalo stampede in the can, the booze artists could drink themselves to death, for all I cared."

The production settled into the Moiese area, renting the town's only hotel as well as a handful of cabins. They were to spend about four days there, during which time they interacted with some of the rangers of the National Bison Range.

In 1965, a cowboy who had worked on the Range named Clarence "Cy" Youngman gave an interview in which he recalled that, "Marguerite Churchill, hell, she'd come riding out there to the corrals one day, and said, 'Hey cowboy.' She says, 'Could you find me a horse? I'd like to go out with you.' I said, 'Just take mine. You can ride this one, and I'll get another one...' She crawled on him, and hell, she went right along with us out there, rode all afternoon, just right along with us."

The starlet, he remembered all those years later, "[t]alked common as anybody else."

To fully realize the scene, Native American horsemen would be needed to give chase to the bison. Forty Blackfoot and Crow men rode to the on-location shoot, kicking their ponies and whooping to demonstrate how they would look on film. Walsh hired them then and there.

But Walsh and his production may have differed from the federal government in their notion of what constituted a "hardship" on the animals: "I did not think that some mild hazing by a few hired Indians would hurt the buffalo... I rather thought the herd would enjoy it."

Finally, the day came. Wayne climbed atop his horse. The Indians prepared to perform a pantomime hunt.

"I had set up on both sides of the route, with the cameras a safe distance away," Walsh wrote. "I yelled 'Cut' when Wayne led the wagons out of camera range, and counted buffalo as the Indians hazed them back to their pasture."

He impresses this point upon the reader: "None were missing and there were no injuries."

An eager Wayne approached him after the scene was in the can. He asked the older man, who had himself lived the life of a cowboy, "How did I do?"

The young man "looked as if he knew the answer" already. Walsh assured him that he had done just fine.

The film was released and was something of a flop. Walsh's autobiography was published in 1974, nearly half a century after The Big Trail was shot. And at any rate he can be forgiven for fictionalizing parts of his own story.

"The Big Trail, after all the worries and doubts," he wrote, "ended fortunately and made money." Perhaps that's true, and the scholars and film theorists who maintain that The Big Trail was a major flop are wrong. Maybe the truth is somewhere in the middle.

Yet there are some facts. John Wayne, despite his early starring role and some positive reviews at the time, did not become the marquee star he would be for the rest of his life until ten years later, with John Ford's Stagecoach. The Motion Picture News reported that the film would be shot on a $1.25 million budget. By 1930, the production cost was reported to be $2.5 million. When it was released, the poster proclaimed it "The Most Important Motion Picture Ever Produced." Box office receipts are, disappointingly, apparently unavailable.

The studios, chastened, did not make Westerns of that size and grandeur again for decades. An easier path was chosen. Rather than long, difficult location shoots, California or a sound stage sufficed. When Indians were called for in the Westerns that followed, they were largely played by Mexicans, Jews, or face-painted whites until the 1970s. The Western, in general, was relegated to a B-movie genre, at least for a while.

Even so, there were plenty who saw it in Montana.

Cy Young, the cowboy lucky enough to be asked to ride with Miss Churchill, said, "I remember that everyone in the whole Flathead Reservation went to Missoula to see it. Stayed there for three weeks."

Another one of the range hands who worked on the National Bison Range remembered another aspect of the production a little differently than Walsh did in Every Man In His Time.

Contrary to Walsh's assertion that there were no missing and no injuries, "Ike" Melton told an interviewer:

"They dug a root-cellar there, just a little low one about this deep. They covered it over with heavy plank, then they made a little slit about this wide in the front there. A fellow sat down in there and laid in there with his camera shooting right at them. They'd run them right straight over him, and some of them jumped right over, you see. One calf run his leg in there, and when he went on over, he broke it. They killed him, or he died of something."

Someone, Melton said, had called Washington, D.C. and told them about the stampede and its bison calf victim. Frank Rose was the warden of the National Bison Range at the time, a rough-and-tumble cowboy who played dumb about the injury. He was, according to man with whom he worked at the time, not well-liked by all.

Per Melton: "Frank said, 'Oh no, we didn't have no loss,' he says. 'Everything went off quiet, and everything was nice.'"

The agent gave him enough rope to hang himself, saying, "'Frank, you says you didn't stampede the buffalo, or nothing [got] hurt?'"

"'No, everything's fine. Never hurt a thing.' So then they up and told him what happened, and told him, by god, 'You just gather your stuff and get out of here in 24 hours. Take your personal stuff and get gone,'" Melton told interviewer Ernest Kraft.

Kraft, in turn, said that "[Frank Rose's] getting so now he can talk about it a little bit, but for years, he couldn't even talk about it, I guess, without just going plumb ape—screaming, and hollering."

Eventually, Frank Rose agreed to an interview in which he told Kraft he couldn't remember exactly why or when he vacated that job.

Perhaps, if we're searching around for a moral, it's that everyone, it seems, from Walsh to Morrison/Wayne to the poor SOB Frank Rose, gets to reinvent their history now and then.

Today, The Big Trail is rightly regarded as a landmark epic, somehow both ahead of and behind its time, and the making of the film is now farther behind us than most of the passages on the Oregon Trail were from the film's original release. In so many ways, the film is as resonant today as it ever was, if not more so. It is also, as with all historical documents, a bit melancholy.

Melancholy came to define the late career of The Big Trail's star. Like so many of the still-living actors of his generation, he had transitioned from big-budget Hollywood films to 30-second television commercials. Marion would have to be reinvented once more, this time as a brand's pitch man. The client, suitably enough, was the Great Western Bank of California. To celebrate their centennial, they had settled on an ad campaign that would eulogize the fading West. They needed someone who connoted grandfatherly dignity, good-faith trustworthiness, and gobs and gobs of Western flavor. The movie star was low on cash. His last movie, his final movie, had been filmed three years before.

On August 25th, 1978, a thinning John "Duke" Wayne rode into frame on a horse. It was one of his last acting gigs, lensed by the great ad man Haskell Wexler, with whom Wayne enjoyed a jovial antagonism. Wayne knew Wexler might be the last director he ever worked with. He knew he was sick, but he wasn't sure what was sickening him, yet.

In the tenor and cadence that was his trademark, he began to speak. He could have phoned it in, but instead he delivered his lines with warmth and presence.

"Beautiful country. You know, I rode out here about fifty years ago on a little dun horse and started a film career. Picture called A Big Trail. Well, I made quite a few since then, some good and some bad. Matter of fact, in those days, a Great Western Savings account would have come in handy."

He would die of cancer 11 months later, his legend secure.

He remains one of the biggest movie stars of all time. In the state of Montana, where his carefully crafted Western image probably has even more appeal than it does in most other states, his face is festooned on countless books, posters, decorative plates, paintings, statues, and murals. You've probably met someone who seems to affect John Wayne's trademark drawl.

For millions all over the world, he remains the Platonic image of the cowboy, just as Montana will now and forever be the far horizon of the eternal West—at the end of the fabled big trail.

Leave a Comment Here