"Shane" and A.B. Guthrie

The Western as a genre has a few titles, literary and cinematic, that can be cited as touchstones for a whole host of stories that followed in their wake. Owen Wister’s The Virginian and John Ford’s 1939 film Stagecoach are right up at the top; Shane is alongside them, both the 1949 book and especially its 1953 screen incarnation. The movie is an enduring classic for a host of reasons, not the least among them the sense of refreshing Western authenticity permeating every frame. An element of said authenticity was bringing in author A. B. Guthrie, Jr., to write a screenplay from Jack Schaefer’s novel. Guthrie’s long attachment to Montana, as well as his own fictional stories of pioneer experience there, carries through into Shane.

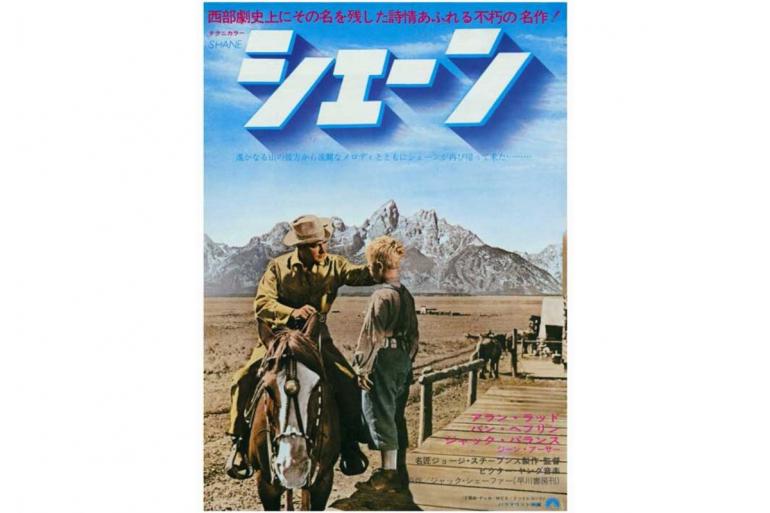

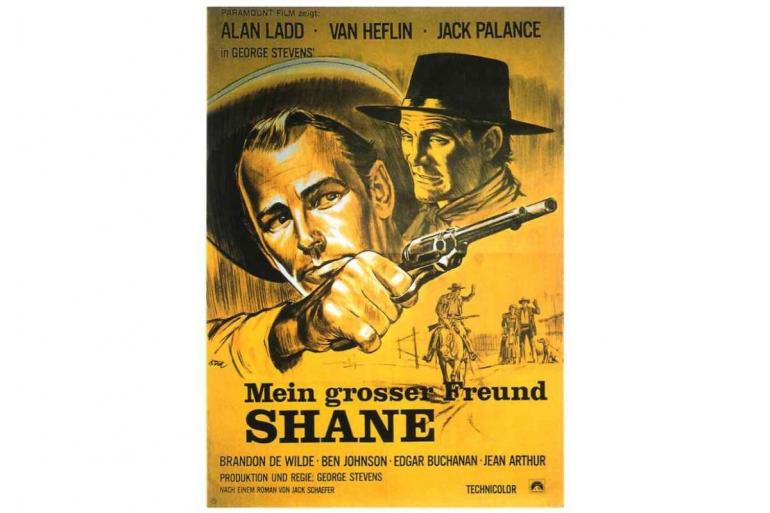

The story is well known. The eponymous character (Alan Ladd, who was cast when Montgomery Clift proved unavailable), a former gunfighter with a mysterious past, rides into a valley where conflict is brewing between a ruthless cattle baron named Ryker (Emile Meyer) and the homesteaders. Shane falls in with one homesteading family, Joe Starrett (Van Heflin), his wife Marian (Jean Arthur, in her final screen appearance) and their little son Joey (Brando De Wilde). He is content working as their hired man, but the threat of violence only escalates, especially after Ryker calls in a hired killer named Wilson (Jack Palance). Shane’s skill with a gun is necessary to save the people who have come to care for him, but it also guarantees that he can never be a part of their lives, leading to one of the most famous, and frequently referenced, conclusions in American cinema.

Jack Schaefer was making a living as journalist when he penned Shane, his first work of fiction. Its eventual success motivated him to quit journalism and continue as an author of Westerns; ironically enough, at the time his writing career took flight he had never been anywhere out in the West. When the film rights were acquired, George Stevens came on as the director. Stevens already had an eclectic resume, having tackled smalltown Americana in Alice Adams (1935), romantic comedy with Woman of the Year (1942)—both starring Katherine Hepburn—action adventure with Gunga Din (1939), and literary adaptation with A Place in the Sun (1951), among other projects. It was Stevens’s idea to approach Guthrie to adapt the novel into a screenplay. Guthrie had no previous experience with screenwriting, but had won the Pulitzer Prize for his novel The Way West (1949), the second book in what became referred to as his Montana trilogy—the other books are The Big Sky (1947) and These Thousand Hills (1956). Stevens had chosen an adapter who not only wrote about the West, but had grown up there.

Alfred Bertram Guthrie, Jr. was born January 13, 1901, in Bedford, Indiana. His parents moved to Choteau, Montana, when he was six months old; he would have an attachment to Choteau all his life. He graduated from the University of Montana with a journalism degree in 1923. After a series of odd jobs, he eventually ended up in Kentucky, where he worked as a reporter and editorial writer for the Lexington Leader newspaper for the next twenty-one years. In 1944 he received the Nieman Fellowship from Harvard, which enabled him to study writing there for a year; Guthrie later credited this experience with facilitating his beginning as a fiction writer. Even as he wrote novels he taught creative writing classes at the University of Kentucky, which is where he was when Stevens approached him about adapting Shane. He was initially reluctant about signing on, but an offer of $1,500 per week for four weeks’ work with additional week-by-week pay was doubtless helpful as persuasion. Guthrie was also fortunate to be given a copy of Schaefer’s book annotated by Stevens with cinematographic suggestions as a guide to crafting the screenplay.

Guthrie’s script follows the contours of the book faithfully, though specific details are different throughout. Character names are altered—“Bob” becomes “Joey,” for example—Joey is younger than he is in the book, and the already present elegiac tone is more prominent. One of Guthrie’s additions is the funeral of “Stonewall” Torrey (Elisa Cook, Jr.), the hotheaded but outmatched homesteader shot down by Wilson in the muddy town street. As Guthrie put it, “I had always wondered about the absence of grief in Western pictures. Here would be bodies strewn all around but where were the funerals and where were the mourners?” The scene in the film not only acknowledges the human cost of the conflict, but also bolsters the complexity of the living farmers; some want to pull out and leave, others feel obligated to stay, and the film is capacious enough to show the points both have.

This surprising complexity is extended even to Ryker; a crucial confrontation occurs at the Starrett homestead at night, where the powerful rancher lays out the trials and sacrifices he and others of his ilk went through to get where they are. He’s still the antagonist, but never one without his motivations. As Guthrie, a student of Western history, put it, “There was no complete right or wrong taken by open-range ranchers and homesteaders. Each side had its case.” The film deliberately evokes the 1892 Johnson County range war; it makes for a striking counterpoint with another, very different movie depicting this conflict, Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980).

Shane was filmed on location near Jackson Hole, Wyoming, in 1951, with its release delayed until 1953. Ironically, at one point Howard Hawks’s production of The Big Sky was shooting in the neighboring valley. Guthrie later went on record saying he regarded the Hawks film as a “turkey,” and he never had complete satisfaction with any of the other film treatments of his books. At least his screenwriting debut went well; in addition to being a resounding commercial success, Shane was nominated for five Academy Awards, including for Guthrie’s screenplay.

It may have lost the statue, but it won out with cultural longevity.

Leave a Comment Here