Billings: Gateway to Western Prosperity

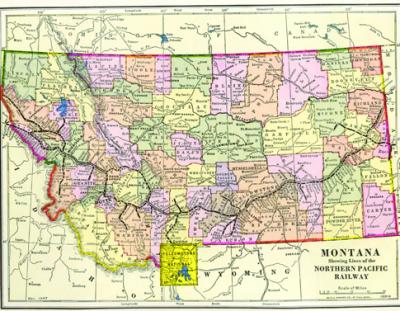

In March of 1882, when the Northern Pacific Railroad laid its first tracks through what is now Billings, Montana, they had an important choice to make: where to set the track. With limited sense of what would soon become massive growth, the surveyors made a strategic decision to draw the rail line down the center as a main artery from which the rest of the town could develop on either side. Heading westward from Minnesota, the Northern Pacific had made the same decision to “center split” other towns of the northern plains like Bismark, Fargo, and Glendive.

What resulted from this seemingly rational city plan was a distinct division of the people to match that of the infrastructure. Billings and other towns along the rail route were shaped to favor one side; and naturally the other side became grounds for all kinds of trouble, poverty and competing ethnic enclaves with their own sub-cultures.

This sociological phenomenon no doubt gave birth to the phrase “wrong side of the tracks.” When the Northern Pacific later expanded and created new towns along its route, the model changed. They realized it made more sense to set tracks on what would be the perimeter of the future town, thus abandoning the original center-split profile. Nearly all major railways, national and international, would follow this same perimeter model into the 20th century.

The original construction of the depot doomed the wrong side to be the one opposite and across its placement. Once it was decided that the depot would be built on the north side, it immediately followed that City Hall, the County Courthouse, the post office, and several churches would all be built to the north as well. Billings’s population more than quadrupled in the years between 1900 and 1920. With that came other new construction that followed suit favoring the north, while the south side became a largely residential sector.

The Parmly Billings Memorial Library, built in 1901, was the first building to face its back to the tracks (and the south side). Soon other buildings on the north side began to do the same and whether it was conscious or coincidental, that row of buildings along the track began to look more like a wall of separation.

Although the south side did have a competing business division, it began to fade as the west end was further developed. The wealthier families and civic leaders like ID O’Donnell took leave from their residence on the south side. Left along Minnesota Avenue and beyond was a true “wild west” scene. Several blocks were made up entirely of so-called female boarding houses split up only by saloons and taverns. They had names like “The Mexico” or “The Palace,” leading one to believe that the ladies there were doing a bit more than just biding their time. Prostitution was big business and it brought with it all the action; poker rooms, opium dens, shootouts and police raids in the night.

The south side also became an enclave for the Chinese and African-American populations with churches constructed for the practice of their own faith, and neighborhoods defined by their own sub-culture. Later, with the construction of the Sugar Beet Factory (which still stands today) workers were brought in from Latin America, Germany, and Russia and given low-wage housing on the south side.

Today Billings is once again experiencing the rapid growth reminiscent of its days as a railroad hub. The geography of the region has given the city’s economy as much dynamic advantage as it did in the 19th century. Billings is virtually the only major city within hundreds of miles; it has people from all around Montana, the Dakotas, and Northern Wyoming doing business there. It is near the Crow reservation. Billings is the regional center of trade and distribution for industries ranging from energy, agriculture and construction to medical, banking and retail. This diversity of the Billings trade and industry gives it a solid economic platform on which to stand when financial troubles rock the rest of the country.

Looking toward the future, the energy sector is perhaps the most significant to Billings’ economy. There are three oil refineries and one coal fire regeneration plant. The city holds a sweet position within the throes of the nation’s largest coal reserves and potentially one of the largest sources of oil and natural gas in the world. Along The Bakken and beyond, North Dakota’s energy boom has delivered a substantial boost to Billings business across the board. Weighing the advance in extraction technologies against government regulation and environmental issues and opposition, it is difficult to say what the future holds and to what extent Billings will continue to benefit from the extraction industries.

This writer has lived in Billings for almost a year now and has gradually discovered the colorful nooks of interest that a casual visitor might miss. He has run miles through the Rimrock formations that give the city its primary boundary; he’s been able to view its shape from many angles. He has visited the state zoo that shelters many of Montana’s native species in captivity and the unique museums, theatres and historical features that give the city its character. At night, he found an impressive community of microbrewers and a busy entertainment scene with improv comedy, local bands, rodeos, trade shows, and other national touring outfits. It’s a fun town without trying too hard to impress, making the appeal of it straight and simple to enjoy.

Billings has been called Montana’s Trailhead or The Gateway to the West and both names seem fitting as one drives westbound along I-90 and gazes out to see the Beartooth and Crazy mountain ranges in the distance. It marks the end of the high plains and the beginning of the Rocky Mountains.

From personal experience, this writer can confirm that special feeling of transition that starts in Billings. Often he has made the journey westward from Chicago where he has strong roots. After a thousand miles drive through flat empty spaces, hitting Billings always renews his sense of home.

Billings is the penultimate driving checkpoint for anyone venturing northwest from the other side of the map for a visit to the national parks or reaching beyond to the Pacific coast. Once the highway traveler has passed “The Gateway,” he or she will rest assured that the long, monotonous drive will end and the reward will be dramatic landscapes and the primordial vibration of the mountain wilderness.

~ Special Thanks to Kevin and the crew at The Western Heritage Center in Billings. Schedule a walking tour this summer at www.ywhc.org/

Boasting the only walkable brewery district in Montana, the Billings CVB recently developed and released this map: www.visitbillings.com/pdf/CVB_BreweryTourMap.pdf. The map enables visitors to explore downtown Billings, the breweries and craft beers offered, as well as the newest distillery, Trailhead Spirits.

--

Leave a Comment Here