Woman Chief and Running Eagle: Nineteenth-Century Women Warriors of the Apsáalooke (Crow), Piikáni (Piegan Blackfeet), and other Plains Tribes indigenous to Montana

Few, if any, aspects of nineteenth-century Native American culture have piqued the interest of the public more than the Plains Indian warrior tradition. Despite the literary and cinematic attention previously devoted to this topic, the participation of women in combat during that period has been largely ignored in scholarly discourse. Many examples of such behavior reflect deeply personal motives, such as the pursuit of revenge for the death of a relative slain in battle, or occurred as instantaneous responses to a military attack on one’s people.

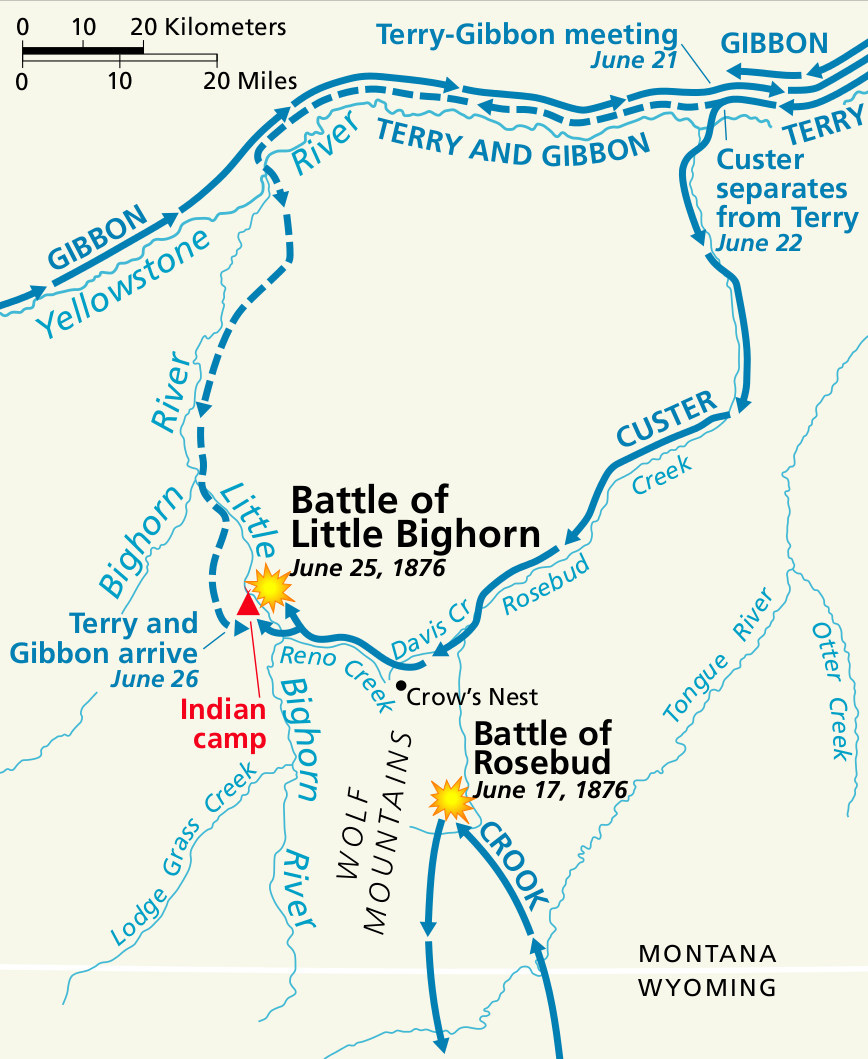

For example, Pretty Shield informed her biographer, Frank B. Linderman, that The Other Magpie, an Apsáalooke (Crow) woman, fought in the Battle of the Rosebud because “her brother had been lately killed by the La[k]ota.” With the assistance of Finds Them and Kills Them, a two-spirit person, The Other Magpie rescued Bull Snake, a Crow warrior who sustained a bullet wound that badly shattered his left leg, just above the knee. Armed only with a coup stick, The Other Magpie rode directly at onrushing Lakota warriors, spitting at them, and exclaiming “my spit is my arrows.” She made physical contact with one Lakota’s horse and counted coup on its rider, just before Finds Them and Kills Them shot and killed their adversary. The Other Magpie then scalped the slain Lakota and, according to Pretty Shield, triumphantly displayed her trophy when the Crow contingent returned to their village.

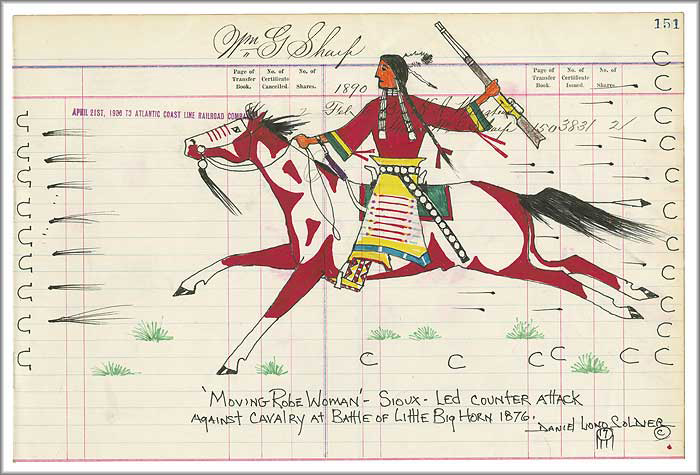

Similarly, Moving Robe Woman was one of at least two Lakota female combatants in the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Also known as Her Eagle Robe or Mary Crawler, she entered the fray after learning that her brother, One Hawk, had been killed. This young boy, known less formally as Deeds, was probably the first Lakota casualty on that fateful day.

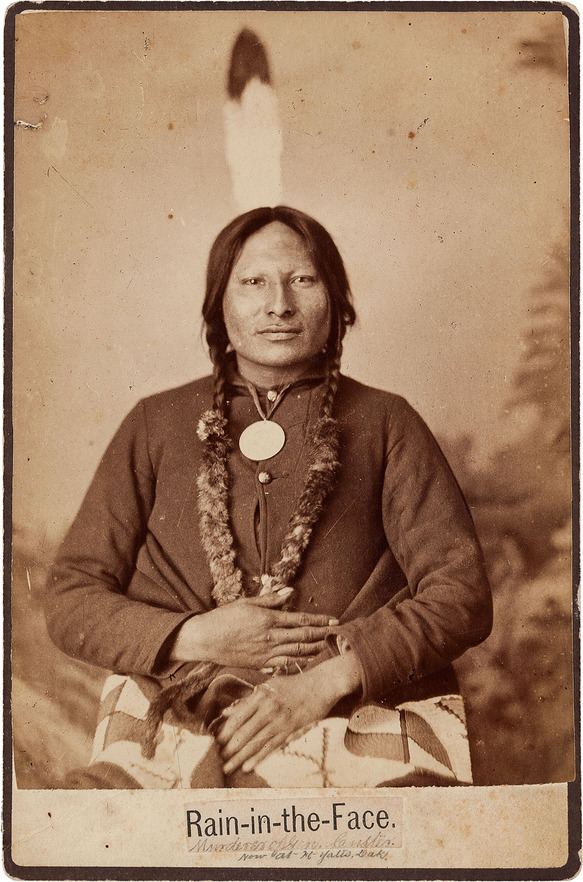

Moving Robe’s involvement in the valley fight was corroborated by Rain In The Face, a Hunkpapa warrior, who utilized her presence as a rallying cry to fortify the courage of his men. As he explained to Charles A. Eastman, “Always when there is a woman in the charge, it causes the warriors to vie with one another in displaying their valor.”

During an interview conducted in 1931 by Frank B. Zahn, Moving Robe Woman was reluctant to divulge details of actions that she personally took in the battle. However, Richard Hardorff, author of Lakota Recollections of the Custer Fight, concludes that Moving Robe “killed two of Custer’s wounded troopers—shooting one and hacking the other man to death with her sheath knife.” Based primarily on the narrative of Eagle Elk, an Oglala warrior and cousin of Crazy Horse, Hardorff also concludes that the man Moving Robe dispatched with her pistol was Isaiah Dorman, a black civilian, who was hired specifically as an interpreter for Custer’s Sioux scouts.

Weasel Tail, a Blood Indian veteran of the intertribal wars, stated that “A lot of the old timers took their wives on war parties.” Young, childless women most commonly engaged in this practice, usually within the context of horse raids. Weasel Tail’s wife accompanied him on five occasions, for which he offered this rationale: “She said she loved me and, if I was to be killed, she wanted to be killed with me.”

According to Father Peter J. Powell, threads of Northern Cheyenne oral history suggest that, within their tribe, “women who had gone to war with their husbands formed their own guild and society,” which held meetings that no one else could attend. He emphasized, however, that “the number of these women among the People was very small.” Nevertheless, Cheyenne women fought in some of the most significant battles in tribal history.

Yellow Haired Woman was involved in two separate engagements during the autumn of 1868. Still mourning the recent death of her husband, she participated in four charges against the entrenched positions of Major Forsyth’s scouts on September 17th in the Battle of Beecher Island. Recognizing that her courage was visibly faltering prior to the fourth charge, Wooden Leg harangued his comrades by shouting, “What are you men doing? You are letting a woman get the best of you.”

Later that fall, Yellow Haired Woman counted multiple coups in hand-to-hand combat by stabbing three Shoshones, one of them mortally. These incidents occurred during the primary and bloodiest phase of fighting in a four-day conflict, which took place near the foot of the Big Horn Mountains. This battle marked the Cheyennes’ greatest victory over the Shoshones, one that resulted in 62 enemy fatalities.

Buffalo Calf Road Woman is probably the best-known Cheyenne woman warrior, since she fought in both the battles of the Rosebud and the Little Bighorn. Indeed, the Cheyennes have long commemorated the Battle of the Rosebud as “Where The Girl Saved Her Brother,” to honor the bravery of Buffalo Calf Road Woman, who rescued her brother, Comes In Sight, from the field of battle after his horse was shot out from under him.

Documentary evidence for the exploits of nineteenth-century Plains Indian female combatants is not particularly rare, given the various scenarios and circumstances cited above. However, very few women chose the way of the warrior as a life-long pursuit. This culturally sanctioned, alternative gender role has been studied most extensively among the Piikáni (Piegan Blackfeet) of Alberta and Montana. Such women gravitated, often at an early age, to traditionally male activities, most notably hunting and warfare.

Pitamakan, or Running Eagle, was the most famous of these Piikáni women warriors. In her case, it is entirely possible that oral history has conflated two women who lived during different eras. Remarks by James Willard Schultz, published in the early twentieth century, vaguely attribute her military career to “the very long ago.” Ken Robison, a local historian, asserts similarly that Pitamakan died about 1836 and was regarded as “one of the first of the Blackfeet to use a gun in warfare.”

On the other hand, anthropologist John C. Ewers interviewed members of the last generation of pre-reservation Blackfeet warriors during the early 1940s, when he conducted ethnographic fieldwork on their reservation. Weasel Tail (ca. 1859-1950), one of his primary informants, recounted the experiences of “Old Chief White Grass, who had accompanied Running Eagle on several expeditions.”

The preponderance of evidence suggests that Pitamakan rose to prominence during the terminal period of intertribal warfare, i.e., the late 1870s. She received a vision, one that foretold success in battle, in a cave near the waterfall in Glacier National Park that now bears her name. Thereafter, Running Eagle embarked on a series of horse raids and war parties, primarily against the Flatheads. Aware of her growing reputation as a war leader, the Flatheads redoubled their efforts to kill Running Eagle and eventually succeeded in doing so during an attempted horse raid against one of their villages.

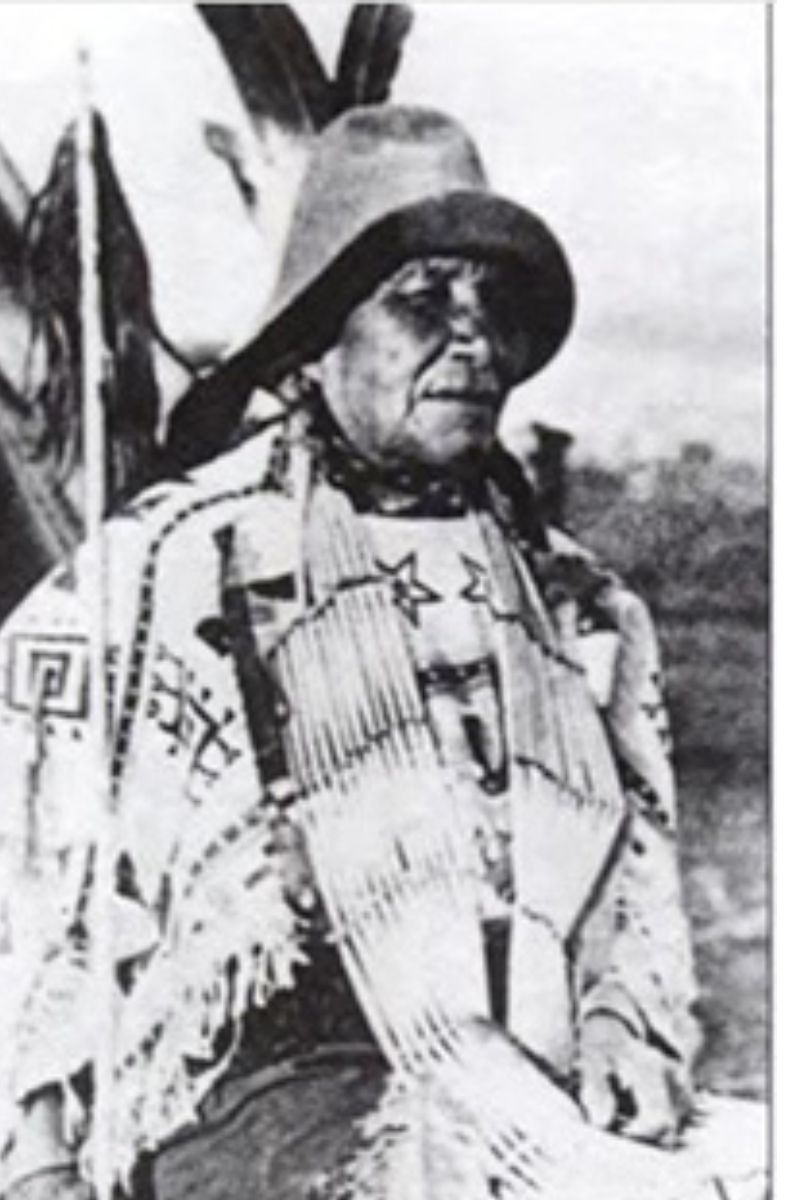

Biographical data on Woman Chief are more abundant and less contradictory, thanks to the writings of Edwin Denig, who was perhaps the most knowledgeable mid-nineteenth century Euroamerican source on the Upper Missouri tribes. Furthermore, Denig’s account is based on “a personal acquaintance of 12 years.” On October 27, 1851, Denig introduced the “famous Absaroka amazon” to Rudolph Friederich Kurz, a Swiss artist who was then visiting Fort Union. In his journal entry for that date, Kurz described Woman Chief as roughly 45 years of age, “modest in manner and good-natured.” Despite her demure demeanor, Kurz emphasized that, on this occasion, Woman Chief presented a Blackfeet scalp to Denig, one that she personally took in battle.

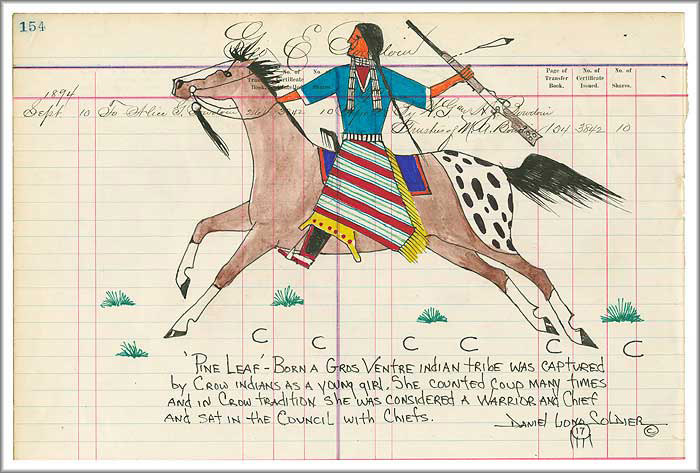

Gros Ventre (Atsina) by birth, Woman Chief was captured by the Crows when she was approximately ten years old. Her foster father quickly recognized and encouraged her interest in hunting and, later, the ways of the warrior. In 1856, Denig observed retrospectively that this remarkable woman compiled a war record so distinguished that it elevated her to a “point of honor and respect not often reached by male warriors, certainly never before conferred upon a female of the Crow Nation.” Indeed, her standing as a war leader enabled her to assume chiefly status, “ranking third person in [a] band of 160 lodges.” Consequently, she earned the right to marry not one but eventually four women, who handled the domestic affairs of her lodge.

After the Fort Laramie (or Horse Creek) Treaty of 1851, temporary peace accords were successfully negotiated between various Plains tribes. During the summer of 1854, Woman Chief traveled north as a diplomatic envoy but, unfortunately, was killed by her biological kin, the Gros Ventre. Some evidence suggests that Woman Chief’s achievements inspired other Plains Indian women to pursue a similar path, but the historical record clearly indicates that nobody equaled, let alone surpassed, her exploits as a woman warrior. “For 20 years,” according to Denig, Woman Chief “conducted herself well in all things appertaining to war and a hunter’s life.”

Leave a Comment Here