The Petrified Man of Livingston Goes East

Western Americans in the 19th century were very much like us; their lives were hard, and they felt they deserved a little entertainment by and by. Like us, many of whom are great fans of true crime or scary movies or paperback thrillers, those Montanans of yesteryear didn't mind if the entertainment was a little gruesome, outre, or weird.

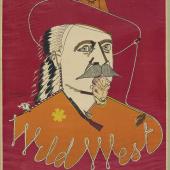

So, amid the larger profusion of oddities like two-headed animals, conjoined piglets, Fiji mermaids, ancient Viking runestones found buried in midwestern fields, bearded ladies, pickled punks, "savages", and other bizarre traveling attractions, there emerged a very specific and surprisingly popular variety: the petrified man.

The ur-petrified man of modern American literary mythology is the hoax contrived by Mark Twain during his days as a newspaperman. Twain called the profusion of touring spectacles the "wonder-business," and set out to lampoon it with a satirical story about the discovery in a cave of a man turned to stone. A slow, steady drip of limestone water had, over a few centuries, fossilized him. Plans were made, he wrote, to blast him out with dynamite so they could give him a proper Christian burial. Perhaps not surprisingly, the joke was lost on many (despite the body's hand having been frozen with its thumb on its nose and its fingers extended in the traditional "nana nana boo boo" pose). As Twain himself put it, "As a satire on the petrifaction mania, or anything else, my petrified Man was a disheartening failure; for everybody received him in innocent good faith, and I was stunned to see the creature I had begotten to pull down the wonder-business with, and bring derision upon it, calmly exalted to the grand chief place in the list of the genuine marvels our Nevada had produced."

And there was, of course, one of the most infamous 19th century hoaxes ever perpetrated against a credulous public. We refer, naturally, to the eight-foot-tall Cardiff giant, "discovered" decades after Twain's creation, and subsequently found to be roughly carved from stone. But not before P.T. Barnum tried to purchase it for $50,000. Rebuffed, Barnum decided to simply "discover" a couple of Cardiff giants of his own.

So it is safe to say that the "petrified man" was well ensconced in the Montanan consciousness well before 1899, when Tom Bunbar started touring his petrified man throughout the state.

So it is safe to say that the "petrified man" was well ensconced in the Montanan consciousness well before 1899, when Tom Bunbar started touring his petrified man throughout the state.

Displayed on a platform in a tent, the petrified man was modestly sized but heavy. A Bozeman Daily Chronicle reporter paid to see Dunbar's entry into the "wonder-business", and wrote "the Petrified Man is 5 feet 8 inches in height and weighs 365 pounds. His hair is perfectly marked, two teeth protrude from the lips, vein markings are visible in the skin, and his hands are tied across the breast with a petrified thong... A bullet hole in his forehead indicated the cause of death." The body was also missing "part of one foot."

Dunbar said that he had found the petrified man on the Missouri River, "in the Fort Benton area." The man was lodged in the sand in shallow water. Dunbar told the New York Times it took "most of a morning to get a rope on him and haul him out of the water."

One imagines that at 365 pounds it must have been difficult, and at one point even the apparently stone man gave way. "That's when the left ankle and the great toe got broken off," Dunbar said.

But Dunbar didn't want to be a showman forever. After reportedly declining a visiting European count's offer of $5,000 for the man, Dunbar sold him to Livingston entrepreneur A. W. Miles. Miles displayed the petrified man himself to even greater success; at two bits a head, he now made some $60 a day off the old boy.

Soon, another tour was mounted. Doctors at every whistlestop were consulted. Inevitably, those doctors would seemingly admit that the body was legitimate. One William F. Cogswell, a doctor for the Northern Pacific, examined the body and said, somewhat confusingly, that "the features are clear-cut and natural. So natural, in fact, does the entire body appear that a person knowing him as an animal could not fail to recognize him as a mineral."

The tour was an unmitigated success - enough for Miles to convince two more speculators (Jardine businessman Harry T. Bush and Livingston attorney Hugh J. Miller) to form The Montana Wonder Company, which offered $25,000 in stock certificates to eager investors who quickly bought them up.

Miles and his fellow investors must have seen the petrified man as the next national sensation, the next Cardiff giant (but real!) when they booked their next tour. What else could account for the sheer audacity of a nationwide expedition that would travel east along the Nothern Pacific's stretch all the way to St. Paul, Chicago, and New York City.

Part of his plan to promote the body was to claim that the identity of the man was none other than famed Irish revolutionary, Civil War hero, and territorial governor of Montana Thomas Meagher, who in 1867 had died somewhat mysteriously on the Missouri River, apparently falling from a steamboat into frigid waters while ill. Speculations about his death abounded then, and still do today.

The idea that the body was Meagher was not entirely without merit. Indeed, while on display in Butte, one miner, having enjoyed a wee nip before the show, exclaimed that it was the General, by god, the General himself! As a matter of fact, that's where Miles got the idea from.

Newspapers throughout Montana eagerly took up the story. Miles hoped that it would be enough to convince crowds in New York City to attend, many of whom were Irish and either adored or hated Meagher for his involvement with the Irish Confederation and his famous Speech on the Dock.

His identification of the body as Meagher was improbably complicated, however, by Montana legend Liver Eatin' Johnson, then in his mid-seventies, who saw the body for himself and proclaimed it was none other than his old friend "Antelope Charley," missing some twenty-five years. This sent a new ripple of stories throughout the Montana presses, but Miles redoubled his efforts to promote the body as Meagher's.

Whoever he was, Montanans had begun to see the petrified man as a matter of state pride, and his Eastern tour was monitored as would be the progress of any other Montana boy made good on the national stage.

Whoever he was, Montanans had begun to see the petrified man as a matter of state pride, and his Eastern tour was monitored as would be the progress of any other Montana boy made good on the national stage.

Sales began promisingly enough but began to dwindle the further out of Montana they went. St. Paul's box office was discouraging, but the extended tour in Chicago was even worse. Miles hoped that New York would still show up in droves. His hopes were dashed, and Big Apple ticket sales failed to cover his costs. It may have been that New York City audiences did not want to pay half a dollar to see something that, fossilization notwithstanding, could be seen for free on the streets.

Miles and his petrified man returned to Livingston in an attitude of defeat. There he was intermittently displayed with waning enthusiasm. Increasingly, he was propped up in a warehouse on Miles's property - not in display, but in storage. A business associate of Miles named C. O. Krohne, who felt that Miles was neglecting a still-fruitful business opportunity, almost succeeded in getting Miles to sell him the body for $2,500, but couldn't drum up the necessary enthusiasm to make it profitable. Finally, decades after he had toured the state and found an ardently appreciative audience, the petrified man was sold for $50. That buyer, name unknown, toured the state with it in a trailer. History does not record the success of his venture; it must not have been great, for the petrified man was sold once more, and eventually stopped touring altogether.

Today, the petrified man is lost to us. No one knows where he is. Or who he was, Thomas Meagher, Antelope Charley, or well-made hoax.

Hopefully, wherever he slumbers, whatever he is, it is given to him, at least, to dream. Perhaps he dreams of crowds. Maybe he dreams of the rocking of a train in motion, of bright lights, or the searching, almost sensual touch of the doctors who examined him at every town in the Treasure State. Perhaps he dreams that he still hears the drawing of tent flaps, the drop of a coin into a box, voices murmuring in naive amazement. Perhaps he dreams of bright lights, fame, and fortune.

Maybe he longs to be found.

Let's find him in whatever crate or landfill he's in now and try it all again. First we'll reacquaint him with his once-adoring Montana crowds, but we'll charge $18.50, the equivalent of 25 cents in 1899. Who's ready to invest?

Then, once he's ready, we'll take him East. This time, let's try Madison Square Gardens, or at least Carnegie Hall.

Leave a Comment Here