Our Interview With Author James Lee Burke

Photo by Frank Veronsky for Simon & Schuster

James Lee Burke, a recipient of the Guggenheim Fellowship, published his first novel, Half of Paradise, fifty-seven years ago, and has written 40 more, with another due this year. He is the author of the extremely popular series of novels telling the story of troubled Dave Robicheaux, sometimes a cop, sometimes a detective, sometimes a sheriff's deputy, and sometimes just a guy in the wrong place at the wrong time as he fights mobsters, murderers, grave injustices, and his own demons. Burke also wrote the Holland series, which covers a century or two of American history spanning from Texas to Montana, as seen through the eyes of the Holland family.

Burke has lived in Missoula for decades now, and both Robicheaux and the Hollands have found themselves in the Treasure State. His most recent novel, Another Kind of Eden, tells a searing story of violence and mysticism among the changing times of the 1960s.

Mr. Burke, who we admire very much around here if you can't tell, has won two Edgar awards for Best Mystery Novel, and was named a Grand Master by the Mystery Writers of America in 2009. His next novel, Every Cloak Rolled In Blood, is another Holland Family story and arrives on store shelves May 17 of this year.

Another Kind of Eden by James Lee Burke

Distinctly Montana: First, Mr. Burke, let me say I'm a big fan. You've written some very powerful and thrilling books, and I thank you very much for continuing to entertain us, disturb us, and make us think.

James Lee Burke: Oh thank you, thank you. It's an honor.

DM: There's a lot of regional specificity to the Montana-set Robicheaux novels. Dave takes his daughter, Alafair, to the now sadly closed Red Skies Over Montana, attends a film at the Roxy, and goes to the legendary Heidelhaus. What made you depict Missoula so accurately?

JLB: I've lived here many years on and off since 1966.

DM: You taught at U of M, right?

JLB: Just three years. '66 - 69.

DM: Robichaux spends most of his time in Louisiana, but two of the novels in that series, as well as two in the Bob Holland series, take place in Montana. How does Montana differ from Louisiana as a setting for crime fiction?

JLB: Yes, New Iberia is my family home. We've lived on Bayou Teche since 1836.

DM: How is Montana like or unlike Louisiana as a setting for crime fiction?

JLB: They're very similar. The issue is minerals. And natural resources. The bad guys want to get into the wilderness areas. It's that simple. They want to repeal the endangered species act. That's the issue. Because it's ironclad.

DM: So, like in the novels set in Montana, most of the bars and restaurants are real places?

JLB: Oh yeah, sure, Louisiana is a giant restaurant and bar room. (Laughs)

DM: While there have frequently been elements of mysticism in your novels (not the least of which is the ghost in In the Electric Mist With Confederate Dead), the latest Robicheaux thriller, A Private Cathedral, takes a bold turn towards horror and science fiction. Another Kind of Eden also involves the paranormal. Why are you embracing the unexplained in your recent works?

JLB: That's a good question. I don't know if I can answer it. I mean to explore the history or the origins of human cruelty. That's it. Where does it come from? Actually, it's a return to the myths of early man. It's really nothing new.

DM: From the Dave Robicheaux novels to the century-spanning chronicles of the Holland Family, all of your main series have eventually come to Montana. Another Kind of Eden also takes place, at least partially in Montana. What compels you to bring your creations to our state?

JLB: John Steinbeck said it all. Montana is not a state; it's a love affair.

DM: You are very much associated with the western crime genre in which C.J. Box, Craig Johnson, and Gwen Florio write. What do you think is the ongoing appeal of that genre?

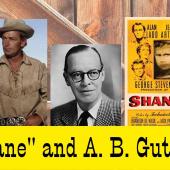

JLB: Well, the Western story actually had its origins in two men only. And those men are John Neihart [author of Black Elk Speaks], and the other, of course, is our friend A. B. Guthrie, my old friend Bud Guthrie. There would be no American West for it not for those two men. But what people call the Western is actually the odyssey of man. John Neihart told me this. He said, "Jim, man follows the sun. He always walks Westward." I was his student. Black Elk Speaks is one of the greatest works ever written about the American Indian and the frontier. It's a tragedy.

DM: Your books have many references to the great works of literature, from Henry James and Jim Harrison in Swan Peak to mentions in Faulkner throughout your oeuvre, and it's hard to think of a more literate (and literary) detective than Robicheaux. It is worth noting that Craig Johnson, also interviewed in this issue, has Walt Longmire, his own detective, read literature to keep his mind limber. How have the great works influenced you?

JLB: I've always believed that great writers are the only ones we should read. That's it. It's like watching bad basketball or bad tennis. You watch those, and it messes up your own game. Read the good ones.

DM: Are there any current crime or thriller writers you particularly admire?

JLB: I think one of the best, of course, is Michael Connolly. He's an old friend of ours and sometimes the people who really - the truth is that Steve King is a theologian if you look inside his themes. And that fellow Tarantino is another one.

DM: Ok, I know our readers will want to know: favorite Tarantino film?JLB: Pulp Fiction, stylistically, changed filmmaking forever. He tells the ending before the beginning. How many guys do that?

DM: Though you have been a writer your entire life, the blockbuster success that has characterized your later work only came to you in your middle age. How do you feel that this experience has affected your work?

DM: Though you have been a writer your entire life, the blockbuster success that has characterized your later work only came to you in your middle age. How do you feel that this experience has affected your work?

JLB: I think it's just nomenclature. All discovery fiction is about crime. Let's go back to Genesis. It's about crime.

DM: Find me a novel without a crime in it somewhere.

JLB: Right. The issue, again, is Dave Robicheaux seeking out the origins of human cruelty. He never solves the riddle. I can't either. I don't know anyone can. I think human cruelty occurs when you allow others to do the unthinkable and hide it from us. When we allow them to hide the unthinkable from us and the most important word is allow. Dachau. Nanking. Hiroshima.

DM: Robicheaux has been played on the screen twice, once by Alec Baldwin and again by Tommy Lee Jones. Do you feel that either actor captured him? Were you ever approached about the possibility of a Robicheaux television series?

JLB: Those were very good actors, and it's a difficult role. That said, I think a television series would allow more expansion of the series, its themes. It's 22 books. 23 maybe! A friend of mine, a director, he and I are hoping to put one together. It's kind of complicated. You learn quickly, in making films, they're real when you see them up on the screen. Until them, oh my, a lot of conjecture.

DM: Robicheaux and the Hollands have been around for a long time now - long enough that there are surely some readers who have spent their entire adult lives following the exploits of your characters. How does that make you feel?

JLB: It's very rewarding because my best work, in my opinion, are the three Holland novels as follows: Wayfaring Stranger, The House of the Rising Sun, and The Jealous Kind. Best writing, best themes, greatest coverage of the west.

DM: What are the three best Robicheaux novels?

JLB: I think they're all mighty good. Laughs. I think what is best in them is the cycle, not of Dave Robicheaux, but instead, the occidental world. That it's really the story of neo-colonialism and colonialism. Dave Robicheaux is the everyman of the medieval morality plays. And all the stories are actually from the bible and greek mythology. The advantage of having a classical education is that few people do, and they don't recognize that the author has stolen all of this material from the Elizabeth theater.

Carl Jung said there is a well that we experience that we inherit in the unconscious. They're just there. I'm kidding about stealing plots, but it's probably a matter of - what we're really talking about; all the essential stories go into either Western or Eastern history. The same stories appear again and again because the stories are indelibly printed in the unconscious of the human mind. A fellow sitting in golly, I don' know, Hong Kong, is reading Macbeth and thinking, "that's my mother-in-law." Lady Macbeth - I based a character in House of the Rising Sun on Lady Macbeth, and I think it's recognizable: heck on wheels. Lady Macbeth is heck on wheels.

DM: Your daughter Alafair is an Edgar award-nominated novelist in her own right. Does the family rivalry consume you both?

JLB: She's always been her own writer. She's been writing since the first grade. She's extremely talented. Her IQ is not measurable, that's a fact - only two in a million have her IQ. I tell this to people, and they say, "your wife must be so intelligent!" (Laughs)

DM: I've seen you compared to Raymond Chandler, whose detective Philip Marlowe was also a troubled by principled man. Do you see Robicheaux as part of a tradition?

JLB: I only read one Chandler. I never read crime novels before, or what people call detective novels. This was my feeling, reading the one book. The author's success, and the esteem which has been shown for his - I mean, golly, he's an extraordinary person, but it's because of his classical education. I think he had a degree from Oxford. The only reason he wrote these books because he was broke in the depression.

Charles Williford was a good friend of mine. Charles was a very good crime writer. Michael Connelly, probably know one knows the territory better than he because he was a police reporter for years at the LA Times.

DM: Do Bosch and Robicheaux have similar ethical compasses?

JLB: I think so. They walk the walk They give voice to people who have none. Dashiel Hammett resigned his job as a Pinkerton because of what he saw there in Butte, Montana. The horrible murder and emasculation of Frank Little, hung from the elevated track of a railroad bridge. Hammet was outraged. That's how he ended up in prison.

DM: Yes, Dashiel Hammett, and the influence of Butte on his work is actually covered in this issue. In many ways, you could make the case that Butte was instrumental in the formation of what we consider the noir novel.

JLB: That said. It was the beginning. Red Harvest. Someone asked him how many people were killed in the book, and he said "I don't know!" (Laughs)

In the Electric Mist film adaptation and novel

DM: When will Robicheaux and his murderous, Falstaffian partner Clete ride again?

JLB: Oh, I just don't know. I went back to the Hollands, and I've got a couple of books coming out about them. We'll see what happens. I just don't think about the future in a work. I never have. I see two scenes ahead, but never more.

DM: Does that mean you don't plan out the plots to the mysteries in these novels in advance?

JLB: No, I don't think so. Characters always come from someplace beyond my grasp. Faulkner put it much better than I. Faulkner said right before hisd eath, "had I not written the books, another hand would have written them for me."

DM: How literally do you mean that? Would you say you're channeling something?

JLB: I can't really answer. Freud believed that a neurosis allows the person to plumb the unconscious in ways that a healthier person would not be capable of doing. It's kind of a left handed compliment. But the stories again, I believe that in every artist they're in the unconscious. But in teaching creative writing, I used to tell students the big story is right out there, right at the other end of your fingertips. The issue is observation. You've got to listen. You've got to look and see. It's right around you. It always is. Great stories are two feet away.

DM: Do you have a favorite Western film? You've mentioned Shane in your writings before.

JLB: Oh yeah, actually, I talk about it all the time. I've been obsessed with "Shane" for a long time. Bud Guthrie again. He did the adaptation. It's not a western, really. It's a classical film. A man with no name. Eastwood played a simlar character. He was a knight right out of Chaucer. What a film, what a film. I never got the little boy's film out of my mind, calling Shane's name. It's one of the greatest films ever made.

DM: It is one of the greats.

JLB: Boy, and Jack Palance. Oh golly. You remember Jack Palance's last words: "I wouldn't push it, to Shane." Suddenly, he's dead. My other favorite line in there is "you're not going to drink those whiskeys, sheepherder," and Shane says to Ben Johnson, "no, but you are," and then he throws the whiskey into his face and then punches him out. I love Bud Guthrie. He was a fine man.

DM: How did you come to know him?

JLB: He was the first person in Missoula I met by accident. It was 1966, my wife and children, and we just had moved into the student and faculty housing, and I saw a tennis court and walked down to it. There was a man playing against the wall, and he said, "get you a racket, and we'll play a game." And he was AB Guthrie. I didn't know his name. I'd never read his name, and I didn't associate him with Shane.

DM: When did you find out he had written Shane?

JLB: It was years later, I still didn't read The Big Sky and The Way West until years later, and actually, we had moved away, and I was just thunderstruck. I believe that those two books are two of the greatest works ever written. I can't understand how others - how the recognition has not come to him. The Big Sky is everything Ulysses is, by Joyce, but better.

DM: That's a bold assertion!

JLB: He's a better writer than Joyce. It's a towering accomplishment, and the best story about Western settlement is The Way West. I think he won the Pulitzer for that.

DM: Thank you for speaking to us and for your contributions both to crime fiction and to the literature of Montana.

JLB: Thank you, you do a great interview. Look me up next time you're in Missoula!

Leave a Comment Here