Ought To Be in Pictures: Yellowstone Film Ranch

How the Yellowstone Film Ranch and the MEDIA Act Are Bringing the Western Back to Montana

Montanans who are more than passingly interested in Star Trek know that southwestern Montana, somewhere around Bozeman, is where humanity first met their eventual space-buddies the Vulcans. In fact, those Trekkies will probably have seen the moment that the pointy-eared aliens stepped out of their ship—surrounded by rolling hills and evergreens. But it wasn’t Montana at all; it was really a forest in Arizona, standing in for the Last Best Place.

It’s a little embarrassing, if you think about it. Like watching old home movies and realizing with a start that it’s not your little brother in the video at all, but someone playing him.

So imagine how much more embarrassing it is for us, as Montanans, when a Western that’s supposed to be set in Montana is shot somewhere else, as was the case with Hostiles, a 2017 Western starring Christian Bale and Wes Studi. At the end of the film they arrive where they’ve been headed the whole time: a valley in Montana. But again, it’s not really Montana.

Maybe Richard Gray and his Yellowstone Film Ranch can help us with that.

Gray was born in Australia, which by all conventional measures of distance is a long way from Montana. But he grew up on Western movies like Jeremiah Johnson, Unforgiven, and McCabe and Mrs. Miller—movies which have helped to define the Western today. For Richie, as he told me to call him, films were an intoxicant. In fact, he told me, his dream since he was twelve has been to make a Western film.

And while he still plans to make one, he might have found something that twelve-year-old might have been even more excited about: making a Western town.

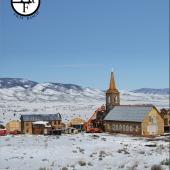

The Yellowstone Film Ranch is composed of twenty-six structures—some 29,000 square feet of screen-ready Western authenticity, including a bank, jail, combination hotel and saloon, livery, blacksmith and various houses and other building. All nestled in the hills outside of Livingston, MT, just minutes away from the legendary Chico Hot Springs.

But Richie isn’t alone on this project. He’s also joined by his business partner Carter Boehm. He is, as Richie tells me, “a long-time supporter of local community and film,” having run the Livingston drive-in theater for years with his family. Carter helped make the choice to bring the project to Montana, preferring to see the tourism and attention go to his beloved state. There’s also Colin Davis, owner of Chico Hot Springs. Richie says he and Colin became good friends during his previous two Montana films, and that Colin told Richie to “build it here,” and thank goodness he did, because the proximity to great lodging, restaurants and recreation has been a “game-changer” for the Yellowstone Film Ranch. Also, I’d be remiss not to point out that their last film, Robert the Bruce (in which Montana sometimes stands in for Scotland), is completed and will be released this spring, around April.

But before you think that they’ve built something like a living history town up there, consider that as a working film set it all has to be built not just to approximate a historical period, but also has to accommodate cameras, crewmen, and directors of photography getting the right shots. It also has to look rustic and a little lived-in.

Which means that designer Lindsay Moran, who has worked with Pixar and on major Hollywood productions like the Hunger Games films, TNT network’s crime drama Animal Kingdom, and others, has to come up with a design that’s a bit less than perfect. If you look closely at the shingles on various buildings, for instance, you’ll find that some of them are slightly mismatched, as if they are the work of a frontier carpenter. In the same way, the metal roof on the town hall building has been treated to look aged and weathered.

In addition to the design challenges, the Yellowstone Film Ranch also has to have the capacity to appear in various film and television projects without it being too obvious that it is the same place. To that end, the town has been built to be geographically rearranged. That means that the church, for instance, has been built on a movable steel frame that, after the outer shell has been removed, can be moved up or down the street. Plus, the location of the ranch was chosen because (like so much of Montana) it looks wildly different depending on where you are looking from; one view of the town shows mountains, the other seemingly endless plains. It could be almost anywhere, except it’s just a bit prettier than just anywhere.

Impressive though they may be, the ranch and Richie’s ambition may not be enough to bring the Western back to Montana, but that’s where the Montana Film Office and the Media Act come in. We might assume, though we may be biased, that if it were down to photogenic beauty, ruggedness and the surprising sophistication of the locals, Montana would always be the ideal filming location. But we can always rely on taxes to make things more complicated.

For instance: have you ever noticed how seemingly every other show on television ends with that little four-note musical jingle that goes “Made in Georgia”? That’s because of the some-would-say aggressively generous disposition of Georgia’s tax laws toward film and television projects, which can earn as high as a 20% credit if they spend more than a half a million dollars in production or post-production while working in the state.

Montana’s beneficence toward Hollywood has varied over the decades, but in May of 2019 Governor Steve Bullock signed the Montana Economic Industry Advancement (MEDIA) Act into law. The sweeping act offers a variety of significant enticements to in-state and out-of-state productions, including a 20% credit of our own. In case you are, like me, a little fuzzy with numbers, I’ll leave it to Montana Film Commissioner Allison Whitmer to explain why that’s a good thing: “The Act went into effect in July and since then, we’ve had an increase in inquiries from film producers looking to film in Montana, and we’ve had people apply for certification to use the tax credit through the MEDIA Act. We’re looking forward to bringing more filmmakers to our state who may not have considered filming here prior to the MEDIA Act.”

As for why that’s a good thing, she makes it even clearer for me: “Film is a powerful tool for promoting Montana. Filming movies, television shows and commercials in Montana elevates the awareness about our state and pumps outside dollars in to our stores, hotels, and to industry professionals.”

So, to return to Richie and the Yellowstone Film Ranch, the project’s proximity to Chico and Livingston are mutually beneficial: as Richie pointed out to me, many similar or competitive filming locations are not as close to civilization as his site. On the one hand, we Montanans enjoy a state with an absurdly, even desolately, low population density. But where we do have civilization, we clean up nicely; crews working at the Yellowstone Film Ranch will have their choice of great steaks and local brews in Livingston, while some other, less lucky crew will be shivering in pup tents somewhere in, oh, I don’t know, let’s say Alaska. Or Arizona.

I drove out to the spot in late November, to have a look around. When I arrived, a brooding fog rolled in over the site, and if you tuned out the sound of power tools and the sight of a few work vehicles parked here and there, I could pretty easily imagine being on the muddy streets of a rough frontier town. It wasn’t hard from there to imagine raucous honky-tonk playing out of the hotel and saloon, or the ominous sound of an outlaw’s spurs approaching.

I look forward to seeing more of the Last Best Place onscreen. If the big risks and hard work of movie fans like Richie Gray and the folks at the Montana Film Office pay off, we’ll be seeing a lot more of her. Most of us Montanans have always known she ought to be in pictures.

Leave a Comment Here

Leave a Comment Here

- Reply

Permalink