Montana’s Most Legendary Apex Predator: Tyrannosaurus Rex

Long before grizzlies became “cocks of America’s Western walks,” as historian John Myers Myers described them, a far more formidable apex predator roamed present-day eastern Montana. Renowned among pint-sized, would-be paleontologists and their professional peers, Tyrannosaurus rex (“tyrant lizard king”) was the lord of antiquity during the Maastrichtian stage of the late Cretaceous Period (ca. 66-68 million years ago).

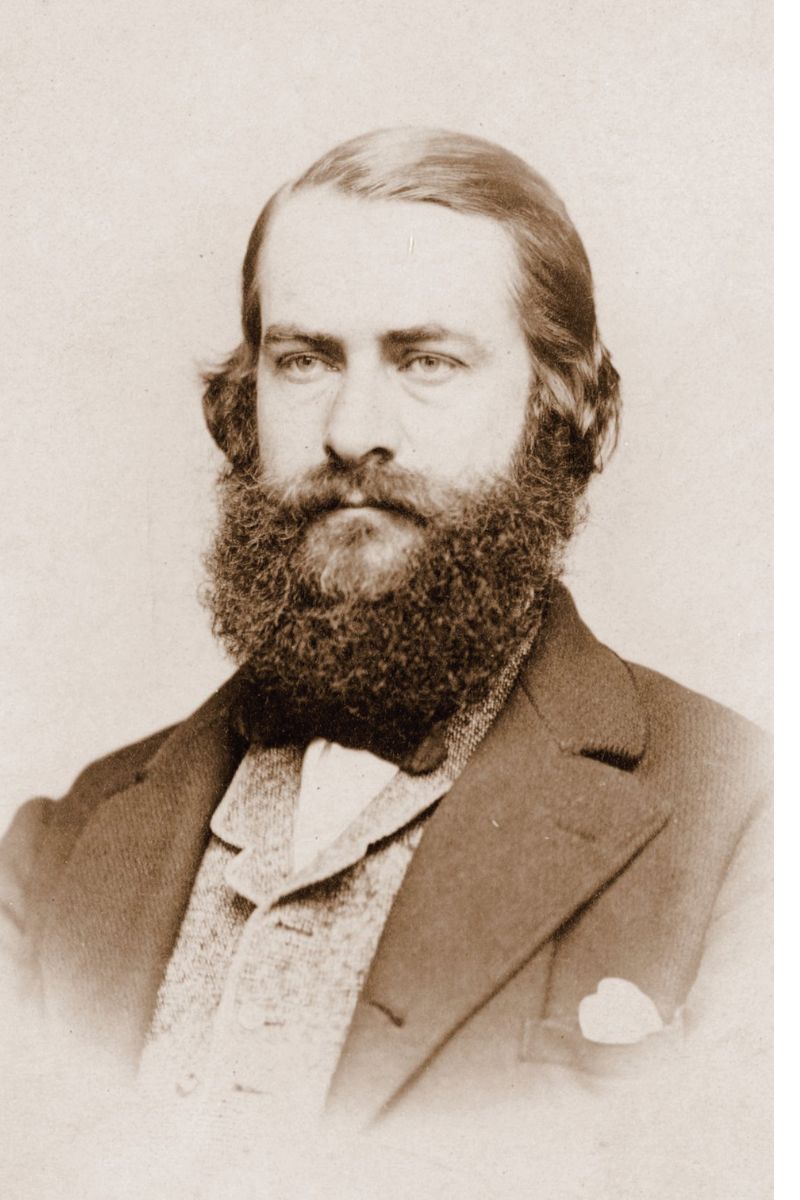

The first scientific evidence of tyrannosaurids in North America was discovered in 1855 by Ferdinand Hayden. Near the mouth of the Judith River, he found several fossilized teeth, which he sent to Joseph Leidy, a paleontologist, in Philadelphia. Leidy concluded that these teeth were of dinosaurian origin, but they differed from those of any previously identified species. In 1856, Leidy classified the remains of this carnivore as Deinodon horridus (“horrifying terrible tooth”).

Isolated skeletal elements and teeth were also collected in 1874 by Arthur Lakes near Golden, Colorado and, in 1890 and 1892, from the Lance Formation in Wyoming by John Bell Hatcher and a party from

Yale University’s Peabody Museum of Natural History. The findings of Hatcher and his colleagues predate other discoveries and initial published references to Tyrannosaurus rex by a full decade.

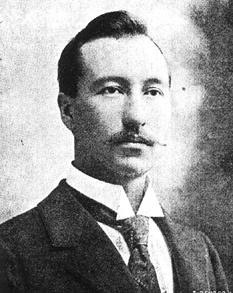

The holotype for T. rex, which is the name-bearing representative of that species, was discovered near Haxby, an old post office north of Jordan, Montana. Excavated in 1902 by Barnum Brown, then curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History, this fossil contains 34 bones, which comprise approximately 11% of the entire skeleton. Originally cataloged as AMNH 973, it was sold to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (Pittsburgh) after 1941, ostensibly to ensure its survival in the event of German bombing raids against New York City.

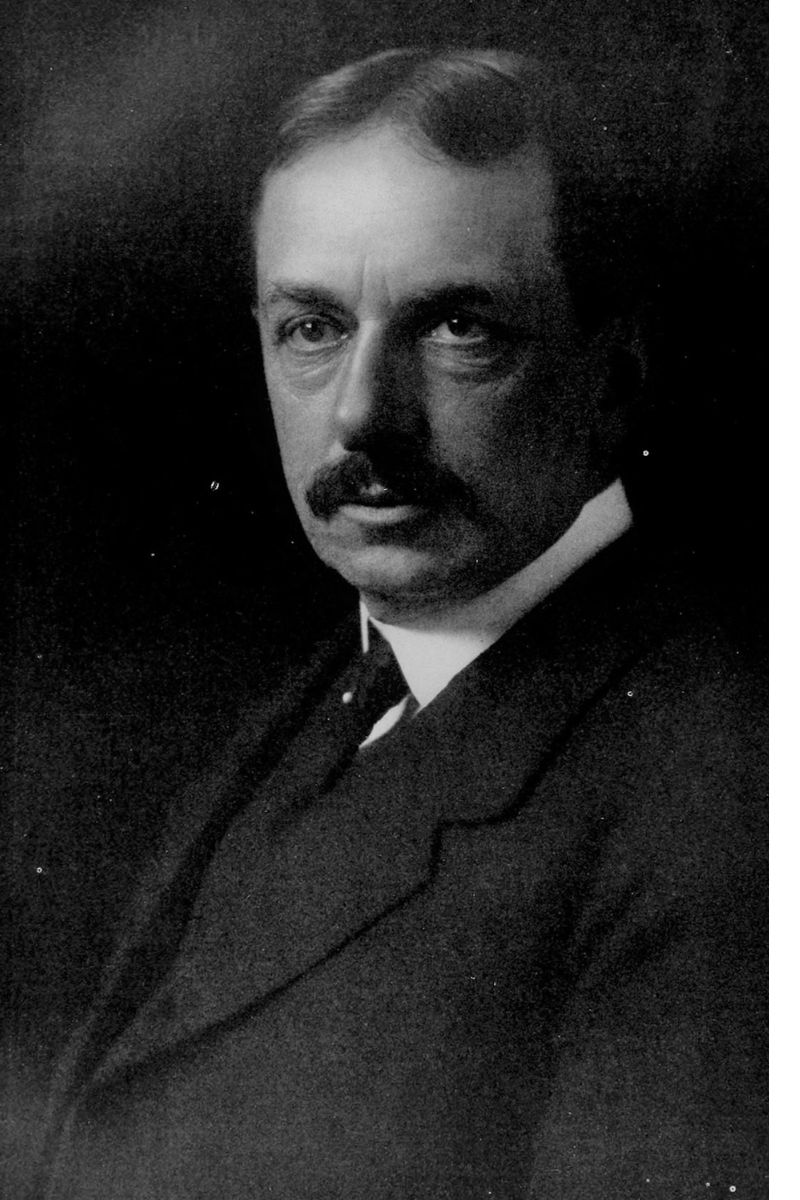

Tyrannosaurus rex entered the scientific lexicon in 1905, when Henry Fairfield Osborn, president of the AMNH, published an article that introduced this species and described its holotype. In 1908, Brown struck paleontological gold in present-day McCone County, where he found a much more impressive representative of T. rex. Containing a complete skull and total of 143 bones, which include most of the rib cage, spinal column, and much of the tail, AMNH 5027 reigned as the most complete T. rex specimen until “Wankel rex” (MOR 555) and “Sue” (FMNH PR2081) were discovered in 1988 and 1990, respectively.

From December 1915, when it was first unveiled, until 1940, AMNH 5027 was the only T. rex skeleton displayed anywhere in the world. Consequently, it became, as Michele Debczak observes, “the most iconic T. rex—and therefore the most iconic dinosaur—in history.”

Contemporaneous works by Charles Knight, the premier paleoartist of his era, also fueled a growing public interest in T. rex, which later contributed to the commercial success of several cinematic productions, most notably King Kong (1933) and Jurassic Park (1992). Similarly, dinosaur figures created for exhibits that the Sinclair Oil Company featured in the 1933-1934 and 1964-1965 World’s Fairs provided artistic grist for advertising agencies. As Donald Glut observes, images produced during or after the latter event were used to promote “anything from the Encyclopedia Britannica to Taco Bell.”

Fieldwork conducted from 1900 to 1912 resulted in the acquisition of eight T. rex specimens. However, “Nearly 60 years [elapsed] before any other skeletons were collected,” according to Neal Larson, and almost 80 years passed before our understanding of this species began to fundamentally change.

Data pertaining to T. rex has grown exponentially over the last 35 years, but the fruits of scientific inquiry in this field will always be limited by exceedingly low rates of fossil preservation. According to Charles Marshall, director of the University of California Museum of Paleontology, “fewer than 100 T. rex individuals” had been recovered as of April 2021, many of which are represented only by teeth or one fossilized bone. Marshall further emphasizes that the “32 relatively well-preserved, post-juvenile T. rexes” in museum collections account for, perhaps, “one in 80 million” of the estimated 2.5 billion that inhabited the earth over the course of approximately 2,500,000 years.

Based on more restrictive criteria and data available prior to 2007, Neal Larson confirms the existence, at that time, of 46 T. rex specimens. Sites at which they were found cluster tightly around Fort Peck Lake. A second group of excavation sites circumscribe the border between southeastern Montana and the Dakotas. At least seven additional specimens have been unearthed since 2006 from outcroppings of the Hell Creek Formation in Montana.

Combining the two datasets, 42 of 53 T. rex specimens were excavated from exposures of the Hell Creek Formation: 26 in Montana, three in North Dakota, and 13 in South Dakota. These sites are most highly concentrated in Garfield (10) and Carter (6) counties in Montana, as well as Harding County (7) in the extreme northwestern corner of South Dakota. Additionally, six skeletons described in Larson’s essay were disinterred from exposures of the Lance Formation in northeastern Wyoming. Both formations were deposited along what was then the eastern coast of Laramidia and the western shores of the Western Interior Seaway.

Numerous outcroppings of these formations contribute significantly to the accessibility and geographic patterning of discovery sites, but they do not accurately reflect the immense breadth of Tyrannosaurus rex habitat. In addition to the areas listed above, the fossilized remains of this carnosaur have been recovered from sites in southwestern New Mexico, northeastern Colorado, Utah, and the southwestern corners, respectively, of Alberta and Saskatchewan.

The Hell Creek Formation is typically interpreted as a forested, subtropical floodplain. However, based on the enormous landmass delineated by discovery sites elsewhere, Larson characterizes the territorial range of T. rex as encompassing “habitats from wet lowland coastal plain environments to cooler alluvial plain settings and semi-arid, upland intermontane basins.”

To take full advantage of its potential for paleontological research, the Hell Creek Project was launched in 1998. Due, in large measure, to fieldwork conducted by consortium institutions, the Museum of the Rockies (Bozeman) became the foremost repository of dinosaur fossils from the Hell Creek Formation. Indeed, its collections include portions of 12 T. rex skeletons, the largest assemblage of its kind. “Wankel rex” (MOR 555), their showpiece, is currently on long-term loan to the National Museum of Natural History, but “Big Mike,” a full-size bronze replica, greets visitors to MOR.

Interestingly, some of the most groundbreaking discoveries in paleontology emerged from analyses of T. rex specimens in MOR’s collections. Wankel rex, for example, provided the first evidence of soft tissue in a fossilized organism. The marrow cavity of a femur associated with “B-rex”(MOR 1125) also revealed a startling feature: medullary bone. According to Dr. John Scannella, this specialized tissue currently is found only in “birds when they're in the process of laying eggs,” thereby confirming this specimen’s sex.

For curious readers, one question typically comes to mind: How big was an adult T. rex? Given the fragmented condition of most fossils, precise measurements are rarely possible. However, a range of size estimates can be generated through comparison of the most complete T. rex fossils. Based on the remains of Wankel rex, “Sue” (FMNH PR2081), and “Scotty” (RSM P2523.8), among others, fully mature adults commonly were 38-40 feet long and 11-12 feet tall at the hips. Estimates of body mass have been calculated through equations that emphasize circumference measurements of weight-bearing elements, particularly the femur and hip bones. Resulting figures vary widely, but researchers at the University of Alberta estimate that Scotty, currently the largest known T. rex, weighed 19,555 pounds.

Is it possible, however, that we grossly underestimate the maximal size of Tyrannosaurus rex? Yes, indeed. Given the tiny population sample available and the difficulty of determining the sex of T. rex fossils, there is no way to ascertain whether T. rex was sexually dimorphic, i.e., characterized by significant sex-based differences in size, as is evident in many contemporary mammalian species in North America. Although their model ultimately rejected the likelihood of pronounced sexual dimorphism, paleontologists affiliated with the Canadian Museum of Nature (Ottawa) concluded, as of November 2022, that the largest T. rex could have been “about 70% bigger” than Scotty. Their findings are controversial, but Thomas Carr, a paleontologist from Carthage College (Kenosha, Wisconsin), regards a T. rex of that size as “within reach statistically.”

Regardless of revelations that may emerge from future research, one constant remains eternal: T. rex evokes a powerful, visceral impression, even after 66 million years. In an article published in 1916, Osborn described Tyrannosaurus as “the most superb carnivorous mechanism among the terrestrial Vertebrata, in which raptorial destructive power and speed are combined.” Ninety-two years later, Gregory Paul echoed those sentiments, when he proclaimed that tyrannosaurids were “the culmination of approximately 100 million years of evolution of gigantic predatory dinosaurs. No other group matched their advanced combination of size, killing power, and speed.” A personal visit to MOR’s Hall of Horns and Teeth will confirm the accuracy of their observations.

Leave a Comment Here