How to Rustle a Cow, How to Catch a Rustler

In an era when foldout cardboard sunscreens include the warning, “Do not attempt to operate vehicle while screen is in place,” it might be prudent to mention that rustling is a crime.

Do not attempt any of the techniques described here.

Rustling falls into several categories, among them subsistence, commercial, brand altering, cow borrowing (or bull borrowing), butcher rustling, and fraud.

Montana Territory was created in 1864, and one of the first acts of the Legislature was to establish brand laws. A brand is sort of like a hot tattoo. Applied by a skilled “iron man,” it causes only enough scarring to make the hair grow back in the shape of the brand.

It didn’t take long before stockmen whose cattle grazed the unfenced ranges to organize to protect their herds from rustling. Roundups were cooperative affairs. If all the ranchers had rounded up their own cattle separately, there was a mysterious tendency for some ranchers’ cows to have twins, while their neighbors’ cows didn’t calve at all. This worked better for the would-be rustler if the calves were a bit older and able to be separated from their mothers. It looked pretty suspicious to see a calf with one rancher’s brand following a cow with another rancher’s brand.

At the low end of the rustling scale was subsistence rustling. One homesteader in Eastern Montana stole two of cattle baron Conrad Kohrs’ steers. Confronted by the owner, the man bowed his head and said, “My family was hungry.” Stern and intimidating at 6’3”, the German-born Kohrs replied, “Well, if they get hungry again, take another one.”

Another western rancher, hearing that a homesteader had stolen a cow, told his hired hands, “If he stole it to eat, tell him to enjoy it and bring me the hide. But if he stole it to sell, by God! bring me HIS hide!”

The hide was important because its brand provided documentation of ownership. Many an unscrupulous butcher ran afoul of the law for failing to produce the branded hides of the animals he dressed out.

It is also traditional, though probably exaggerated, that a cattleman never slaughtered his own animals, the theory being that this amounted to eating up his profits. The standard joke was that a rancher, invited to dine at a neighbor’s was pleased to have a chance to eat his own beef.

These were minor matters, but rustling on a large scale was serious. In an early example of white-collar crime (though precious few collars were white on the open range), unscrupulous foremen would report up to 80% calving success to their absentee owners, some of whom resided as far away as Scotland. The true figure was closer to 50%. Montana’s legendary Hard Winter of 1886-87 provided a golden opportunity to clear the books of cattle that had never existed in the first place.

The Cut Bank Pioneer Press reported that in the early 1880s, the Frewen Brothers bought 3,500 head of cattle from the 76. (Ranches were generally known by their brand.) When the cattle were delivered, they counted hundreds up Rattlesnake Canyon and hundreds more up Fish Creek, all with the proper 76 brand. Unbeknownst to the new owners, the 76 cowboys knew a shortcut up Horse Creek to Fish Creek, and the Rattlesnake Canyon cattle were double-counted. Modern rustlers resort to the rustling of cyber cattle, but cyber detectives stay on their trail. And although the dollar figures may be high in cyber crime, there is this to be said for doing things the old-fashioned way: You can’t eat virtual beef.

It’s hard to bear a grudge against Sim Roberts, though he was undoubtedly a rustler. Around 1882, Cattleman John T. Murphy, suspecting Roberts of rustling, inserted silver coins just under the skin of some of his cattle. He planned to retrieve the coins before witnesses to prove ownership of the animals, but received a letter in the mail one day. Out fell a handful of dimes, and an anonymous note” “A big cattleman like you shouldn’t be so careless with his money!”

Some rustlers operated on an international scale, stealing Montana cattle and driving them across the border to Canada, then returning to Montana with stolen Canadian cattle. One such operation in 1896 was broken up when a mysterious stranger hired on at a ranch near some of this nefarious activity. A good worker, he was forgiven unexplained absences. Some might have suspected him of rustling, but the truth came out when he identified himself as Sgt. T. B. Kilgore of the Canadian Mounties and arrested a gang that had perpetrated the cross-border thefts.

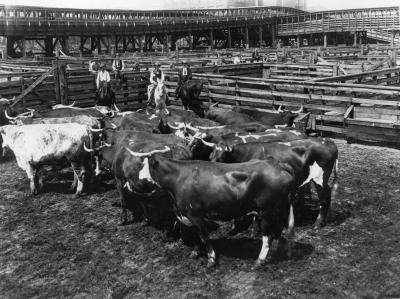

Stock detectives on both sides of the border worked to catch rustlers; they worked shipping points as far east as Chicago. These men had an almost encyclopedic knowledge of brands, as well as the skill to read brands, which were nearly illegible to other’s eyes.

Reading brands is complicated by the fact that the brand grows as the animal grows, becoming less clear than the compact mark put on a calf. Add to this the work of a skilled “rewrite man,” and it’s not surprising that an amateur may have trouble deciphering the marks and even a brand inspector may need to shave the hair around the brand to expose it cleanly.

Imagine you have been lucky enough to register a simple S brand. Clean and open, it makes a clear and easy to read mark. The rewrite man comes along with a running iron or a heated cinch ring held between two interwoven green sticks and suddenly your S has been turned into a - 8 - (Bar 8 Bar). The change can be detected when the animal is butchered, as the scar tissue on the inside of the hide will differ between the original brand and the change.

Of course, killing a valuable member of the breeding herd to prove it is stolen isn’t a perfect solution: “Yep! It was stolen all right. Now it’s supper.” These days a biopsy may provide less invasive proof. Even DNA testing can be applied. This is particularly useful in the case of the “rustling” of a prize bull’s “potential” for AI (artificial insemination).

That is an extreme case of bull borrowing. A simpler method employs a good pair of wire cutters between the neighbor’s fine bulls and one’s own cows. The bull is a co-conspirator in this crime.

Cow borrowing takes more time. A good cow may be “borrowed” from another rancher for four or five years if the range is large and rough enough to provide concealment. Her calves receive the guilty rancher’s brand, and the cow will mysteriously reappear on the owner’s land when she ceases to be a useful breeder.

Variations on the theme of cattle crime and punishment will probably continue as long as there are range cattle, rustlers, and livestock detectives, but whether changing a brand or hacking cattle transactions on a computer, it would be well to remember that romance of the Old West notwithstanding, it’s not a good thing to be branded a thief.

~

Leave a Comment Here

Leave a Comment Here