East to Gold Mountain: Chinese Miners in Montana

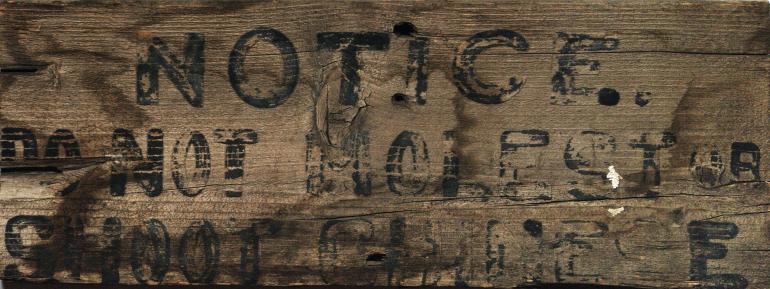

Photo by Sherman Cahill, used with permission of Mai Wah Society.

Beginning in the 1850s, many enterprising Chinese workers emigrated from China to the United States. Spurred on by a recent dramatic increase in the Chinese population, and destabilized by the collapse of the Qing dynasty, thousands sought better opportunities in a younger land, one so seemingly overrun with resources that they didn’t have enough labor to get them out of the ground. So they headed east, to the American West, which they called “Gold Mountain.”

Like the rest of the world, the Chinese felt the lure of the possibility of an easy fortune at the striking of the California gold rush. Soon, however, that gold rush had dried up, and the Chinese who had settled in California moved into other careers or other sections of the West.

And when Montana experienced its own gold rush, many Chinese came to Bannack and Virginia City to seek their fortunes; the first mention of Chinese arriving in the area was in an 1865 issue of the Virginia City newspaper The Montana Post, which groused at the arrival of a small group of gold-seeking Chinese workers.

In 1870 they were numerous enough to prompt a study performed by the federal government, which reported that:

“The Chinese work their own placer claims, either taking up abandoned ground or purchasing claims too low in yield to be worked profitably by white labor. The ground thus obtained sometimes turns out to be very valuable, but usually they work or rework only what would otherwise remain untouched... They are frugal, skillful, and extremely industrious. Frequently maltreated by evil-disposed whites, they rarely, if ever retaliate.”

Source: Butte Silver Bow Historical Archives

The Works Progress Administration authors of Copper Camp: The Lusty Story of Butte, Montana, the Richest Hill on Earth again reinforce their hard work and determination as miners, saying that “there was a deep-born spirit of adventure in the early Chinese, who had, seemingly, an inherent urge to find out what was on the other side of the mountain... Here, as elsewhere, they were content with the leavings of the white miners. They panned the overlooked sandbars, dumps and other neglected places, and as was usually the case, in the end made more of a success out of their gleanings than did the original locators.”

But some workers adopted a xenophobic view, saying that the Chinese were taking jobs and claims from American workers, and in 1872 the territory passed the brief-lived “Alien Law” that tried to keep Chinese workers from purchasing or owning property, including placer mines. Historical evidence suggests it was scantly enforced. Following a case involving a Deer Lodge County mine owner named Fauk Lee, the law was struck down by the territorial supreme court. Many Chinese mining interests were successful, and large sums of money were exchanged—just in 1871 and 1872, Chinese companies bought some $106,600 worth of mining claims in the German Gulch area. In today’s money, that would be about $2.2 million.

As more Chinese arrived, they became an important demographic of Montana’s population. Though there were only around 2,000 Chinese emigrants in Montana in the year 1870, you might also consider that that represented about 10 percent of the population of the territory. By 1890, the heyday of Chinese emigration to Montana and the United States in general, there were 2,532 Chinese immigrants living here.

Inevitably, gold mining declined in Montana, but advancements in technology and demand led to silver and copper mining, which would dominate the state’s mining efforts for more than a half-century. Many Chinese emigrants pivoted from mining to commercial industries that supported mining, such as operating laundries, vegetable gardens, dry goods stores, medical practices, and other ventures. At the same time, Chinese labor was important in the construction and timely completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad. There were also those markets that, though they proved popular with some significant portion of the public, were not entirely “respectable” at that time: places to gamble, to smoke opium, and even, according to Copper Camp, stores that sold fine “French lingerie and silk hosiery,” establishments set up, not coincidentally, in the red-light district.

Source: Butte Silver Bow Historical Archives

One of the most significant businesses operated by Chinese were noodle parlors, especially beloved in Butte, where there were parlors to match any consumer’s needs: some were opulent and gilt, some were small and cramped, some were expensive, some were cheap, but nearly any resident of the mining city could enjoy a bowl of Chinese food, whatever their station. They were so central to the community of Butte that, according to William Burke, “After dance, show or celebration, it was the custom of the Butte bloods to end the evening by a visit to the noodle parlors.”

In 1882 the Chinese Exclusion Act, a much more damaging piece of legislation than the territorial Alien Law, was signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur. To this day, it remains the only law ever passed in American history that aimed to prevent the entirety of a specific ethnicity or nationality from entering the country. More specifically yet, the text of the law proscribed that no “skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining” would enter the country for ten years. Renewed again in both 1892 and 1902, the act was decried by Republican Senator George Frisbie Hoar as “nothing less than the legalization of racial discrimination.” Sadly, the law would stay on the books until 1942, when we allied with the Chinese against the Japanese in WWII.

The Act made life very difficult for those Chinese already living in Montana for various reasons, including a shortage of Chinese women, who were vastly outnumbered by the men. Gradually, the number of Chinese in Montana and the surrounding states declined, as it did across the country. By 1943, Copper Camp reports that “All is quiet in... Chinatown... The population has dwindled to a handful. Most of these are now withered patriarchs who sit over their long pipes and talk about the good old days.”

But of course, that’s not the whole story, because some of the Chinese families stayed, despite the difficulties. Partly because some exceptions to the Chinese Exclusion Act were made for merchants and other non-worker class Chinese, there were some families who managed to establish long roots in Montana, and some businesses that survived, and even enjoyed a rousing success for dozens of years, chief among them the Pekin Noodle Parlor in Butte, the oldest operating Chinese restaurant in the country as well as the oldest restaurant in Montana.

Such stories serve as particularly poignant examples of the fabled “American Dream.” Because, like so many grand Western narratives, the Chinese-American experience in the 19th and early 20th centuries is a tale of hard work, perseverance, and for those who would continue to call Montana their home, a story of adversity overcome.

Photo by Sherman Cahill, used with permission of Mai Wah Society, Butte, MT

Leave a Comment Here