St. Marie

Montana's Newest Ghost Town

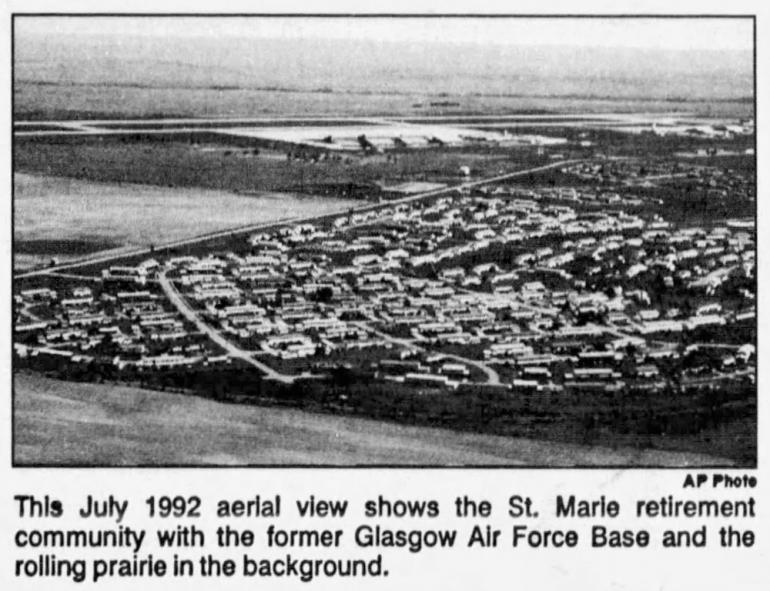

Heading north out of Glasgow on MT Highway 24, you’re painfully aware of how flat the landscape is. It’s as flat as a basement floor in every direction, the horizon broken only by an occasional silo. Fifteen miles north of town, though, something begins to take shape. As you approach it, the shape becomes houses. Lots of them. A couple of water towers join the skyline. It looks like you’re coming up on a little Montana town, out here in almost-no-man’s-land. And it is a town, or rather, was. More than a thousand homes stand clustered along gently curving streets, creating a large neighborhood of duplexes, small apartment buildings and single-family homes. Up close, the houses are clearly in sad shape. Paint flakes off the walls, garage doors hang crooked on mangled tracks, and broken-out windows and weather-ravaged roofs signal years of neglect. Wildly overgrown yards have pushed grass through the sidewalks and into the streets. A low-slung, brick hospital looks as though a bunch of shambling zombies may burst out of the double doors at any moment. And not too far away languishes a high school that looks like it hasn’t seen a student since the days of disco and Pong.

The effect is disconcerting. It looks as if on some unseen signal everyone who lived there suddenly jumped into their cars and left en masse. Front doors stand ajar on several homes, revealing cupped linoleum tiles and faded formica counters in the kitchen, where you might not be surprised to find cold cups of coffee and perhaps an ancient cigarette slotted into an ashtray.

You’ve found St. Marie, Montana’s newest ghost town. A couple of ratty, abandoned homes might not be that striking, but string together street after street, many lined with hundreds of ramshackle houses—that’s when curious turns creepy. A sign near the entrance reads, “Welcome to St. Marie: Home of the Adventurous.” Considering St. Marie’s compelling story and hazy future, that might be a bit of an understatement.

At its peak in the mid-seventies, more than seven thousand people called St. Marie home. The community was established to provide housing for the servicemen and their families stationed at Glasgow Air Force Base, a cold war airfield built to accommodate B-52 bombers and KC-135 refueling transports. The base was decommissioned for good in 1976 and St. Marie emptied out virtually overnight. Neighboring Glasgow saw a corresponding drop in population—by 1980 an exodus comprised of 16,000 people had left Valley County, and today it holds fewer than 8,000. Usually when a town loses its sole economic engine, the area is repackaged or razed to make way for another chapter in its history. Fate had other plans for St. Marie.

It wasn’t even known as St. Marie until after the base closed down. In the mid-eighties retired Air Force officer Patrick Kelly bought 1,225 empty housing units from the federal government for $520,000 and started running ads in military magazines touting the retirement community he planned to build. St. Marie, named to honor his daughter, would provide the self-contained isolation and squared away community that military retirees favored, he claimed, promising such amenities as a bowling alley, recreation center and a golf course, not to mention world-class fishing at Fort Peck Lake less than an hour away. Kelly, originally from Sidney, had always loved Montana’s northern plains and figured the appeal would be an easy sell.

It did not work out the way he’d hoped. After unloading fewer than a quarter of the units in ten years, he ran out of money and sought funding to keep his little enclave afloat. After piecing off parcels for several years, in 1996 he sold his remaining interest to a Seattle property developer which promptly went bankrupt and was eventually convicted on several counts of securities fraud. By this time St. Marie was home to a couple hundred people—mostly retired military—although no services were available in the community save for a post office, a town hall, and a condo association that maintains the occupied properties. Glasgow remained the go-to for everyone’s needs.

Fast-forward to 2012, and Kelly had fallen behind in tax payments for hundreds of the remaining properties. The housing market had driven up costs, even in St. Marie. Several owners had declared bankruptcy, and condo sales tapered off. Financially strapped, Kelly was unable to move forward on any renovations. So most of St. Marie sat empty and dilapidated, seeming to sag earthward with each passing year, along with Kelly’s dream.

And then the Sovereign Citizens showed up. In 2012 a couple of men from Ephrata, Washington, working under the name DTM Enterprises LLC, filed tax liens totaling $212,686 on 483 units in St. Marie. Kelly was given sixty days to come up with the payments or DTM would effectively take ownership of the houses. Terry Lee Brauner and Merrill Franz were members of an anti-government group called the Sovereigns, an extremist movement that spurns such meddlesome governmentmental mandates as driver’s licenses, law enforcement, courts and, of course, taxes. The FBI describes the group as “paper terrorists” who became known for inundating the courts with frivolous lawsuits and punitive liens. Brauner and Franz had gained Kelly’s trust by promising to rehabilitate the structures in St. Marie to provide housing for the workers of the booming Bakken oil field 150 miles to the east.

Brauner soon began showing up at community meetings in Glasgow and became a regular at the Valley County courthouse, where his refusal to obtain a Montana driver’s license, among other things, put him on the wrong side of the law. The Sovereigns unleashed an avalanche of lawsuits against the homeowners and residents of St. Marie, suing over such things as the division of community property and access to public roads. No Trespassing signs containing threatening language and repeated references to the Constitution popped up all over St. Marie. Kelly quickly soured on the sovereigns’ hijinks and warned his neighbors that the newcomers would be expounding their radical philosophy. The local judiciary, fed up with Brauner gumming up the courts with his bogus lawsuits, shut down the sovereigns’ fusillade of paper, but not before several St. Marie residents had to pony up court fees to defend themselves. Having worn out their welcome, DTM eventually gave up their attempted takeover and moved on.

Brauner soon began showing up at community meetings in Glasgow and became a regular at the Valley County courthouse, where his refusal to obtain a Montana driver’s license, among other things, put him on the wrong side of the law. The Sovereigns unleashed an avalanche of lawsuits against the homeowners and residents of St. Marie, suing over such things as the division of community property and access to public roads. No Trespassing signs containing threatening language and repeated references to the Constitution popped up all over St. Marie. Kelly quickly soured on the sovereigns’ hijinks and warned his neighbors that the newcomers would be expounding their radical philosophy. The local judiciary, fed up with Brauner gumming up the courts with his bogus lawsuits, shut down the sovereigns’ fusillade of paper, but not before several St. Marie residents had to pony up court fees to defend themselves. Having worn out their welcome, DTM eventually gave up their attempted takeover and moved on.

Meanwhile, Kelly had been working through other channels, seeking an investor who could bail out his beloved community. Enter Michael Mitchell, a commodities trader who pumped $400,000 into the St. Marie Development Corporation. By now Kelly’s vision for the St. Marie development was fast approaching quixotic, and according to sources who were involved in the subsequent lawsuit, acted unilaterally, making promises that he could not deliver on. Fed up, most of the board members split off from Kelly and pursued their own ventures, buying up some of the properties for themselves. In 2018 Kelly was found liable for fraud in Valley County District Court and was ordered to pay Mitchell more than $13 million.

Today, the twisted legal and financial trails of St. Marie are hopelessly tangled, like colored lines on a crumpled road map in the glove box of an old farm truck. During its periods of confusion and conflict, houses were sold with little regard to property lines, making title insurance impossible to secure. Who ultimately owns what, and will St. Marie live to see its winding streets buzzing with life again are questions that may as well be directed at a Magic Eight Ball—“reply hazy, try again”. The current ownership is a jumble of renters, Airbnb’s, condo and homeowners whose population hovers around 200 hardcore residents comfortable living about as far from the hustle and bustle of urban American life as you can get. The notoriously brutal eastern Montana winters punish these aging structures, which are then pummeled by the sand-blasting winds and suffocating heat of summer. And yet the physical shell of St. Marie still stands, like a herd of bison bracing themselves against a prairie snowstorm. But unlike the bison, St. Marie sees no rebirth in the spring. The pastel-colored houses lose a bit more color and a few more roof shingles blow off every year as this lonely and ill-fated town, once home to thousands of people, slowly fades away.

Leave a Comment Here

I only wish that you interviewed some of the current residents. We drove through there on our way to Scobey. People live there and do they have electricity? Mail? And is the Montana Aviation Research Company still in existence? So interesting and fascinating.

Thank you and I hope to learn more.

- Reply

Permalink