Bound in Blood: The Freemasons and the Vigilantes

On April 27, 1805, the Lewis and Clark expedition passed into what is now Montana via the Yellowstone River, and so Meriwether Lewis became the first Mason to set foot in our fair state. Or perhaps it was Clark, depending on who was standing in the front of the boat.

After all, Lewis had been trying to convince Clark to join his fraternal Brotherhood as far back as Pittsburgh, as the pair waited out the construction of their first keelboat. History doesn't record whether Clark had agreed to do so by the time they'd entered Montana, but he would officially join the Freemasons on September 18, 1809, in St. Louis Lodge No. 111, two days after it was founded.

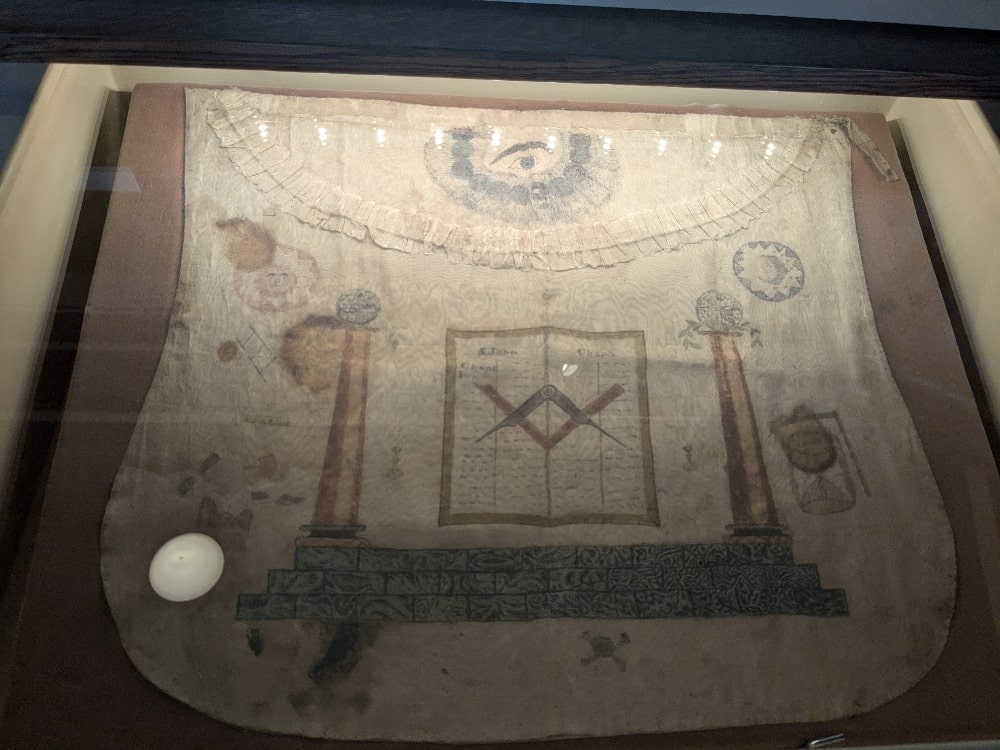

It would take some time for the seeds of freemasonry to take root in Montana, but, slowly and surely, they did; fifty or so years later, three men held the first formal opening and closing of a lodge on the Mullan Road on September 23, 1862.

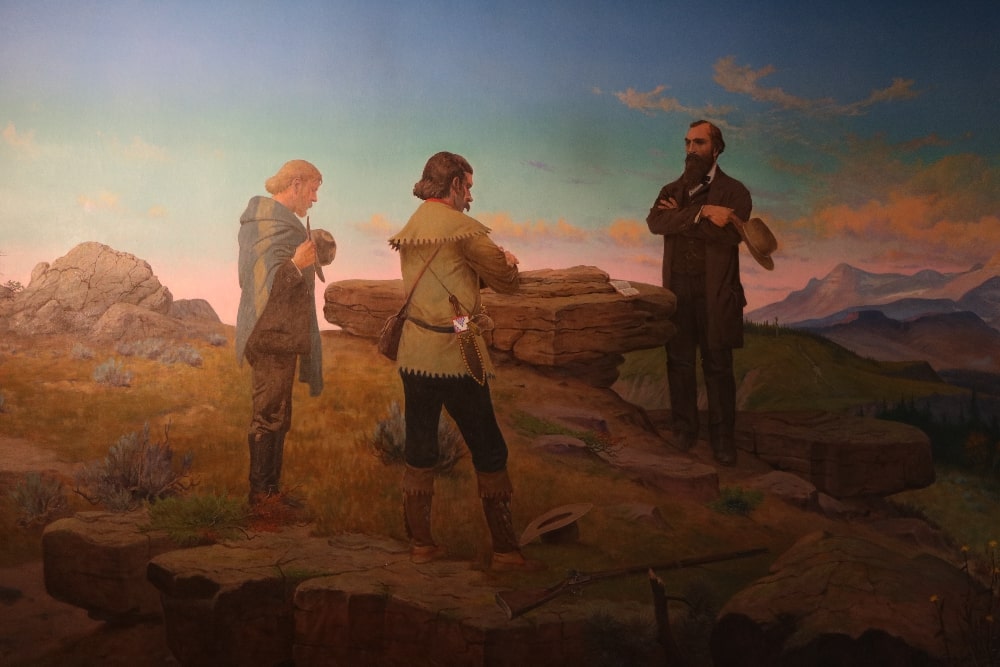

There, at the seat of the Rockies, Nathaniel P. Langford, George Gere, and David Charlton* performed the rituals that marked their brotherhood as Freemasons. Langford, later a writer of several essential works of Montana history, proclaimed that "never was the fraternal clasp more cordial than when in the glory of that beautiful autumnal evening, we opened and closed the first Lodge ever assembled in Montana... and when we left the summit of that glorious range of mountains, to descend to our camp, each felt that he had been made better and happier for this confidential interchange of Masonic sentiment."

The moment is captured in a mural by legendary Western artist and Charlie Russell protege Olaf Seltzer. Commissioned for the Grand Lodge in Helena, the painting now stands in Montana's freemasonry museum, where it stirringly represents the moment as a heroic, even foundational event in history.

And by any measure, it was, for the Freemasons proved integral to Montana's history, and the nation's; villainized by some, lionized by others, they succeeded, over their 200 years in Montana, in establishing over 82 lodges and initiating thousands into the sacred mysteries of their ancient order.

Two months after the opening of Montana's first impromptu lodge, Montana's Freemasons held their first funeral. The deceased was one William Bell, and as tradition has it as he was on his deathbed he requested a true Masonic funeral. Langford, moved, called for all Freemasons currently in Montana to attend. Langford didn't expect many to show and was moved to find that 76 men came to honor their Brother.**

To Langford and to the other Masons present, the unexpected appearance of so many of their brethren showed that, on the frontier, Masonry could be a powerful tool to build and keep social relationships. It must have provided at least a degree of comfort to Masons of the day that, at least in principle, any fellow Masons they encountered while in the wilderness would be a trusted Brother to them.

One story, related by Langford at an address given to assembled Masons, demonstrates the value of being a member of a global fraternity that is at once far-reaching, and very secretive. A few days before the first meeting on the Mullan Road, a few riders dressed as mountain men descended from the hills to speak to the Fisk expedition. All but one of the riders passed by, but the last one stopped to speak, asking who owned the wagon train, how many men were present, and so forth. Langford happened to overhear as the rider, apparently indistinguishable from any other frontier character except that Langford worried, for a moment, that he was perhaps a road agent, asked a strange question:

"'Was there a man named H. A. Biff in your train?"

Langford watched as a member of the expedition told the rider that "no such man" was with them.

"'Did you ever hear of such a man?"

No, they responded. They "know of no one of that name."

Langford, as a devoted Brother, knew that H. A. Biff was a reference to Hiram Abiff, legendary chief architect of Solomon and the ur-Mason of lore. The rider, Langford knew, was sounding the group out for Masonic associations.

Langford eagerly approached the man when he was away from prying ears. According to Langford, "We employed the time we were together in relating each to the other his Masonic experience, and bearing mutual testimony to the satisfaction we had derived from the Order, and to its peculiar adaptability to our condition in this new country."

In short, a "friendship was thus formed, through the instrumentality of Masonry, which could not otherwise have found existence."

For one man with the unlikely name of Paris Pfouts, and surely many others too, it provided an opportunity to meet with like-minded individuals without indulging baser instincts. And, in a frontier filled with temptations toward vice, in which many of the social avenues for men to meet and enjoy fellowship involved drunkenness, fighting, thieving, and the rental of female company, that could prove rare.

But what could all that secrecy purchase? Friendship, certainly. Brotherhood. Community. But is it possible that members of this benevolent order, meeting in obscurity on the Montana frontier, could employ all that secrecy and obfuscation in service of conspiracy?

Or put plainly, did some of Montana's burgeoning Freemasons plan a series of vigilante killings?

Within a year of that first official meeting, a group of seven men would meet in Nye and Kenna's Dry Goods Store in Virginia City. Two of them, Wilbur Sanders and Paris Pfouts (who would be elected their president), were Masons.*** Though the rest of the men do not appear to have been Freemasons, it seems clear that the secrecy and camaraderie of the Ancient Order influenced all of those gathered. Secrecy would have to be paramount, naturally, because the topic of conversation was as solemn as the grave: the killing, perhaps justified, of some badmen.

As Langford recounted later, "Suffice it to say that, attracted by the promises which this Territory gave of the easy acquirement of wealth, a great number of the hardened villains who had infested the various mining camps on the Pacific slope, assembled here for the purpose of availing themselves of such opportunities as might offer to depredate upon the hard earnings of the honest and laborious people of the Territory."

Against this backdrop of worsening crime in the gold camps of Montana, a known troublemaker named Ives had tried to kill a man named Holter in a botched robbery. His bullet had passed through the man's hat and grazed his scalp, but had left him alive. The gunmen cocked his pistol, leveled it, and pulled the trigger again, but the gun failed to fire. Holter, a Norwegian businessman who would later have great success in Helena, ran away in the moment of confusion caused by the misfire and managed to reach town and report that Ives was his attempted murderer. A few days later, the mutilated body of a well-liked young man named Nicholas Tiebolt was found, and locals rightfully suspected that Ives, and some other local roughnecks, were involved. A posse was dispatched to find and arrest him. After a trial, Ives was lynched in front of a crowd.

Against this backdrop of worsening crime in the gold camps of Montana, a known troublemaker named Ives had tried to kill a man named Holter in a botched robbery. His bullet had passed through the man's hat and grazed his scalp, but had left him alive. The gunmen cocked his pistol, leveled it, and pulled the trigger again, but the gun failed to fire. Holter, a Norwegian businessman who would later have great success in Helena, ran away in the moment of confusion caused by the misfire and managed to reach town and report that Ives was his attempted murderer. A few days later, the mutilated body of a well-liked young man named Nicholas Tiebolt was found, and locals rightfully suspected that Ives, and some other local roughnecks, were involved. A posse was dispatched to find and arrest him. After a trial, Ives was lynched in front of a crowd.

The Masons and their brothers in conspiracy resolved to form a vigilance committee like the one that had arisen in San Francisco in 1856, and in so doing to kill or drive away the criminal element, including Ives's cohorts and, eventually, the crooked sheriff Henry Plummer, whose gang, it has been estimated, was responsible for dozens of murdered travelers along the territory's roads. In the months to come, fifty or so citizens volunteered to be vigilantes. They would kill nearly 30 men, most but not all confirmed outlaws and ruffians.

Historian and associate justice Mark C. Dillon writes, in his book The Montana Vigilantes, 1863-1870: Gold, Guns, and Gallows, that Freemasonry "may have been a factor in the growth of the Vigilance Committee in Alder Gulch and in the trust that its early members had for one another... The fraternal bond of the Masons paralleled the bond of trust that needed to exist among members of the Vigilance Committee, and in some instances the bonds of one may have helped the other." Nevertheless, Dillon points out, "The Vigilance Committee was nevertheless a separate organization and by no means the arm of the Masonic Lodge."

Even so, it has to be pointed out, as Dillon does, that "by the time Paris Pfouts [the president of the vigilantes, and a Mason] left Montana in 1867 for St. Louis, he had become High Priest and Captain of Hosts of the Royal Arch Masons Chapter, Prelate of the Knights Templar, and Conductor of the Council of Royal and Select Masters." Freemasonry, it seems, had done well enough for him.

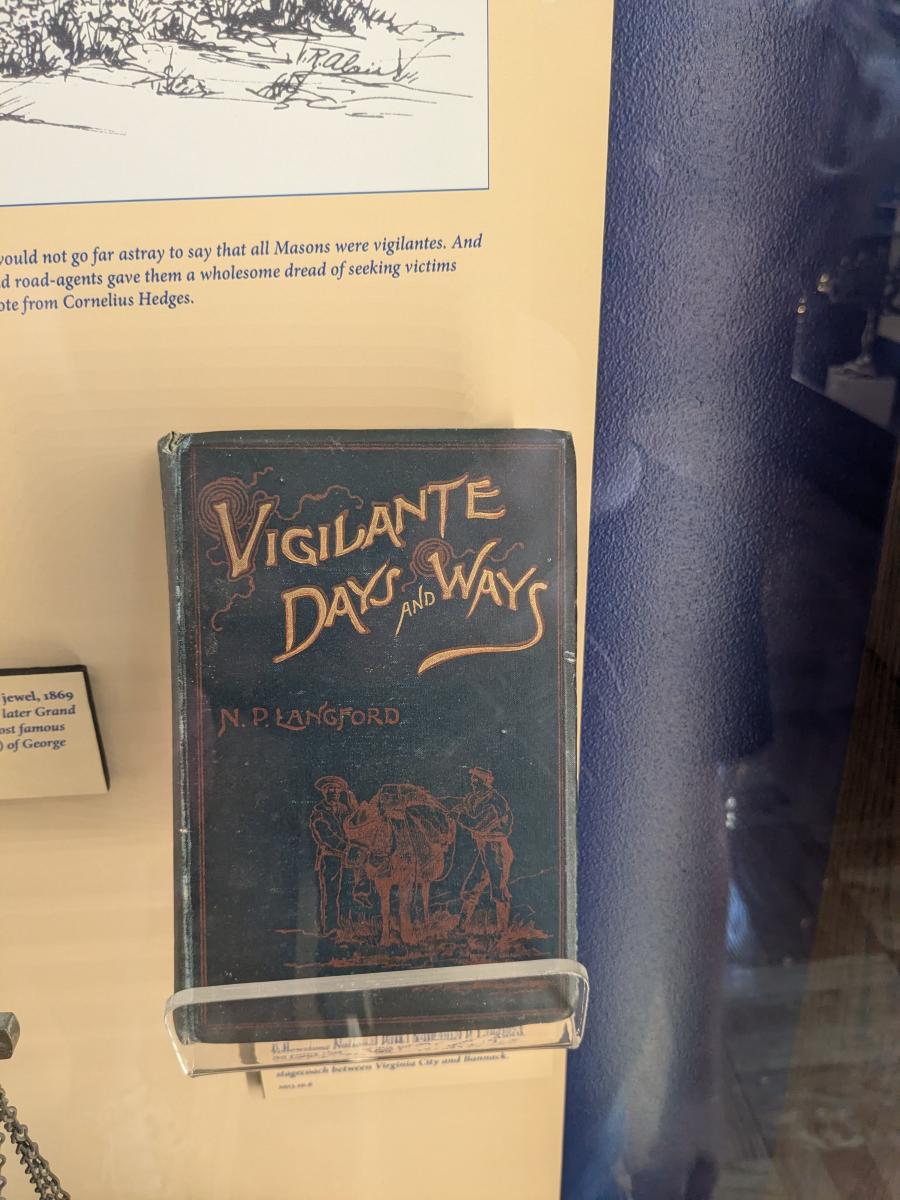

The specifics of those original vigilante killings and their Virginia City sequel have been explored elsewhere in more detail than we could manage here, and the reader is invited to seek out one of the many excellent books written about those events, including Langford's own Vigilante Days and Ways. George Brown and "Erastus Red" Yeager were captured and compelled to name their accomplices before being hanged. Sheriff Henry Plummer, among those named, went to his reward. Not long thereafter the unrepentant cannibal Boone Helm, local bootmaker and alleged outlaw Clubfoot Georg, and four of their alleged friends were dispatched. "Greaser Joe" Pizanthia expired after three shells of artillery blew apart his house and gravely wounded him, but not until the posse of vigilantes shot him again. The vigilantes continued to Hell Gate, where they rounded up three men, gave them two trials between them, and hanged them all. The next day, they caught up with two more suspected road agents; they tried them and hanged them. The next day they cornered Whiskey Bill Graves, arrested him, and hanged him the day after. And so on.

Still later, in the 1870s, another series of extra-legal hangings were performed in the name of so-called "vigilance." In this climate, 3-7-77 first became associated with viligantism, employed as a grave warning by none other than Montana Supreme Court Justice Lew Callaway (a Freemason) in 1890s Virginia City. Intended to scare off some rough vagrants who had made their way to the town, its wording seems redolent with the kind of institutionalized clandestineness that characterized both Masonry and the vigilantes:

"3-7-77

ATTENTION

A meeting will be held at the usual House and

Place, Sunday evening. As Business of Importance

has arisen, a full Attendance is Requested."

Eventually, the escalating violence, particularly in Helena, where a hanging tree was long employed for that purpose until a photograph of a double lynching scandalized the state, became so overwhelming that newspaper editor Robert Fisk famously called for stemming the tide of recent vigilante terror by returning to "decent ordinary lynching."

The Masons, meanwhile, had spread throughout the state, and if the vigilance committee had begun with the tacit approval of Virginia City's Masons, some other Brothers had decided that it didn't augur well for the future of justice in Montana. As historian Frederick Allen pointed out, by 1879, the first time that "3-7-77" appears in print, vigilante justice would have brought no small degree of shame to high-ranking establishment Masons such as Hiram Knowles, a recently retired territorial justice (resolutely anti-vigilante, as an avatar of the legal system) who had ascended to the post of Montana's Masonic grand master. The grand secretary, for his part, was also a probate judge. As Allen observes, "The use of numbers signifying a link between the vigilantes and the Masons would have embarrassed both men."

And for good reason, as American Freemasonry was about to enter its golden age. From 1870 until 1920, fraternal orders in America entered a "golden age." It is particularly telling to note that of the 45 presidents, 15 of them have been Masons, and, with apologies to George Washington and James Madison, most were after 1870. In these halcyon days of American Masonry, membership soared and many men across the United States grew to greet each other with secret handshakes that revealed their degrees. In short, Montana's Freemasons, at least for a while, sought to disassociate themselves from the actions of Montana's vigilantes.

The spread of the Freemasons was only checked by the same decline that has threatened all social clubs and fraternal orders—fewer and fewer young people join the Elks, the Knights of Columbus, or the Ancient Order of Hibernians. Though Freemasonry remains by far the most famous and influential organization of its kind, membership is overall on the decline.

Today, Montana is replete with Masonic temples, if not with Masons. Lodges persist in Montana's biggest cities, along with Philipsburg, Glendive, Anaconda, and more. Lodges in Pony, Baker, and Ismay have surrendered their charters and vanished into Masonic history, sometimes leaving once-grand buildings shuttered.

Masonry will never really go away, though. Institutions on the scale of Freemasonry don't disappear, they wane. And when their season returns, they thrive once more.

A new generation of young men might find in Freemasonry the answers to questions that they didn't know they were looking for. They might find companionship and the drive to improve themselves, a place where they can learn ancient secrets passed down to them over generations. A place, as their clarion call goes, to "make good men better."

And those initiates, bonded and brothers and honor-bound, would do well to remember the words repeated during their first-degree initiation, the same words that were intoned by Meriwether Lewis, by Charlie Langford, and countless others.

Most scholars maintain that the wording is metaphorical, not intended to be taken literally; even so, they are told, Freemasons should keep their secrets vouchsafed, or, having failed to do so: "...have my throat cut across, my tongue torn out by the roots, and my body buried in the rough sands of the sea at low water-mark, where the tide ebbs and flows twice in twenty-four hours; so help me God, and keep me steadfast in the due performance of the same."

Compared to a fate like that, a simple hanging rope seems like a tender mercy.

* These three men, some say, are the source of the 3 in 3-7-77, the oft-debated "mystic numbers" that symbolize, at least in the collective imagination, Montana's vigilantes.

** Some say this is the source of the number 77 (the assembled men plus the dead man) in 3-7-77.

*** A persistent rumor has it, even among some amateur Masonic historians, that all of the men who met on that night were Freemasons. Indeed, the evidence suggests that only two of the seven were Masons. Nevertheless, some hold that the 7 in 3-7-77 refers to these men.

Leave a Comment Here