Bair Family Collection of Western Art

One of the most respected and admired patrons of art in the history of Montana is Charles M. Bair. He and his family’s legacy endure through their multiple philanthropic endeavors and charitable donations. Bair’s reputation thrives because of his benefits to the people of Montana, including good relations between Native Americans and ranchers. Another great and lasting gift that his family has lovingly given to Montanans is their appreciation of culture, impeccable taste, and a carefully assembled eclectic collection of worldly treasures.

Charles Bair, founder of what became a Montana art legacy, came in on a train from Ohio with only “fourteen cents and seven green apples”, according to author and Bair historian Lee Rostad. His job as a conductor on the Northern Pacific Railroad had taken him to Montana in 1883. From that point on, Bair would consider Montana his home, slowly investing in land and eventually in sheep. Known as the “sheep baron,” Bair became one of the largest owners of sheep herds, running 300,000 head at the peak of his career. After getting caught up in the Klondike gold rush in 1898, Bair made a fortune by investing in a machine made to thaw out frozen ground with hot water. He returned to Montana to continue with his activities in ranching as well as in banking, real estate, coal and oil development, and irrigation projects, mining and utilities.

Bair married Mary Jacobs of St. John’s Michigan in 1886. They went on to have daughters Marguerite and Alberta, who are credited with putting together what is now the Charles M. Bair collection.

Like any good father, Bair wanted to provide every opportunity available to his girls. Mary and Marguerite explored cultural education and social environments while Alberta was more of her father’s daughter, known for her knack for business and playing cards or golf with the men. While both daughters enjoyed hunting, Alberta was still deer hunting well into her eighties. Charles M. Bair passed away in 1943 but left his daughters with a sense of the importance of using their vast financial resources for philanthropic purposes.

Before the girls made Martinsdale their permanent home in 1934, they had lived all over the country, attending colleges in Missouri and Pennsylvania, living in Portland for years as well as in California in the winters. These experiences led to their desire to collect, to bring pieces from their fantastic adventures back home with them, and to be able to share with their Montana friends the treasures that the world had to offer.

The Bair sisters soon joined the elite club of becoming private collectors. There is an amount of freedom that private collectors take pleasure in that museums often do not have. When building collections, museums generally aim to obtain works in a systematic approach specific to periods and movements, or particular themes and eras are explored through acquisition. Private collectors, on the other hand, are free from being bound to patterns of collection and can draw from their own particular inspirations or passions. The strength of the private collection is in expressing the collector’s creative interests. Therefore, an appreciation of a private collection requires an understanding of the collector’s vision.

The Bair vision was of eclectic origin. Alberta and Marguerite Bair traveled to Europe 20 times over the course of their lives, finding treasures that not only were significant in documenting historical periods, but which shaped the vision the two sisters designed for their final gift to the people of Montana. The vision was to not only show Montanans the treasures the world had to offer, but to integrate them with the beautiful pieces executed by Montanans and westerners as well.

Lee Rostad referred to a world-renowned collection when describing the visions that Alberta and Marguerite had when organizing their own collection. The Wallace Collection, a London house museum, holds one of the most significantly eclectic private collections in the world. Lady Wallace bequeathed the collection to the British government, one that holds everything from French 17th and 18th century furniture, objets d’art, to paintings by old masters and modern French artists, exhibited alongside arms and armour, medieval objects, bronzes, ceramics, clocks, miniatures and porcelains. When looking at the Bair collection it is clear that the intentions were very similar between a nineteenth century English noblewoman and two twentieth century women from the farmlands of distant Montana.

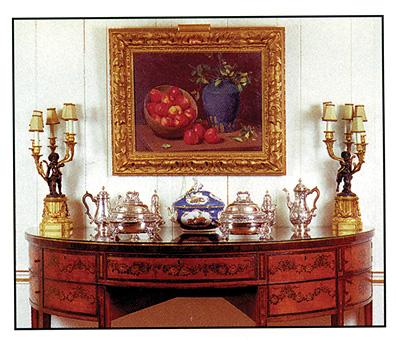

The two collections share a similarity in the decorative objects found around the houses. The Bair estate holds such fine objects as a fine French clock in the boulle style, an early 18th century design by Andre Charles Boulle, a favorite designer of French royals. Louis XV was of particular interest to Marguerite who found such objects as a desk, chest, commode, candlesticks, and a portrait of his daughter Henrietta by the royal portraitist, Jean-Marc Nattier.

It is fascinating to see the way in which the two girls based their collections. They appeared to be loyal to collecting items that they enjoyed looking at, but also found ways in which to relate their Montana world with the centuries of European treasures they came across.

The favorite hunting Palace of Britain’s William and Mary, called Het Loo, was an inspiration to their collection as well. Meissen porcelain, German porcelain that was highly sought after by 17th century collectors, and Sevres porcelain, French porcelain also held in the highest regard by royalty including Catherine the Great, were among the objects collected from the palace. A museum conservator remarked upon discovering a Sevres urn a few years ago, “The museum world has been wondering what happened to these urns. Wait until I tell them they are in a ranch house in Montana!”

Anecdote after anecdote could be told about the women and their adventures in collecting: silver by the famed English goldsmith Paul Storr, paintings by French artist Eduoard Cortes, brilliant Persian carpets, Chinese Foo Dogs, and Adam style Greek urns. But Alberta and Marguerite wisely chose also to include in their space the treasures of American craftsmen.

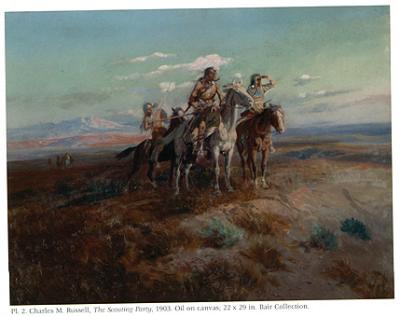

Because of Charles Bair’s diverse business ventures, he was able to encompass a large range of associates and friends. Among those with whom he had excellent rapport with were the Crow Indians, from whom he leased land. From that relationship, Bair developed friendships with Crow chieftain Plenty Coups and artist Joseph Henry Sharp, who painted on the reservation each winter. Bair became a patron of Charles M. Russell, commissioning two of the collection’s paintings -- “The Scouting Party” and “Roping a Steer.”

Increasingly patrons who commissioned works directly from artists were succeeded by collectors who for the most part bought historic works indirectly from dealers. Some of these collectors, who on occasion were also patrons, sought to furnish a “western room” in their residence or acquired works with such fervor that their collections soon exceeded available space. Specialized collections exist in terms of strictly directed European treasures or the distantly western collections of Indian artifacts or western paintings.

Landscape artists Herring and Cole, as well as Montana artist J.K. Ralston, are included in the collection of fine paintings. Personal notes from Charlie Russell and autographed photos of various Presidents and First Ladies are also proudly protected by the collection. Among the photography collection are some phenomenal works by famed photographer Edward Curtis, who was taking photographs of the Crow Reservation when Charlie Bair had invested in the same area.

Native American treasures were important to the collection including incredible Navajo rugs, Pacific Northwest and Southwest woven baskets, as well as various objects from the Sioux and Crow nations. The vests of Crow chieftain Plenty Coups and one of Buffalo Bill’s bartenders are some of the objects collected by the women with the same vigor and excitement that they paid to the treasures not native to their home.

Two stone pineapples atop the front gates welcomed guests to the Baur home but sadly, Alberta and Marguerite were unable to see the collection viewed by the public. Marguerite passed away in 1976 and Alberta in 1993. Rostad tells the charming story about how the hall bench held several hats belonging to the two ladies. Before answering the doorbell, Alberta would don one of the hats. If the visitor were a friend, Alberta would say, “We just got home. Do come in.” If the visitor were a salesman or unwanted guest, her reaction was, “I’m so sorry we can’t ask you in. We were just going out.”

Alberta and Marguerite should now be celebrated for assembling this phenomenal collection, which they planned to leave within the house as a museum “which would perpetuate the historic and artistic significance of the Charles M. Bair Ranch and the people associated with it.” In 2004, the Yellowstone Art Museum in Billings exhibited about 50 works from the Western and American Art part of the Bair collection with the idea of celebrating the interests of this grouping of history.

The Bair collection also serves as an example for present and future collectors. Because if today’s collectors are lucky or really know what they are doing, they too may have the honor of seeing their collection sought by a museum, or perhaps, most fortunately become a museum for all to share.

~ Erin W. Anderson is a freelance writer and art historian. She studied at MSU and Sotheby’s Institute in London and currently is an adjunct instructor at MSU.

Leave a Comment Here

Leave a Comment Here