Fort Benton, Town Born of the River

Fort Benton today is a small town of only about 1,500 inhabitants, which ranks it as the 75th largest “city” in the state. Despite its size, Fort Benton holds the title “The Birthplace of Montana,” and for good reasons. It is the longest continually inhabited white settlement in the state and, during most of the nineteenth century, it certainly was the most important city in the pre-statehood Montana Territory. The Missouri River was a major trade artery that reaches deep into the continental U.S. With its strategic location on the Missouri River as the furthermost navigable point inland, the settlement became the focus of most things that either came into or out of Montana until the arrival of the railroad in the late 1880s. The river was the inseparable heartbeat of Fort Benton, and gave Fort Benton a very colorful, checkered past—one which has undergone more changes over the years than a runway model at a fashion show!

It was near present-day Fort Benton that Captain Lewis and his small party rendezvoused with Clark and the rest of the Voyage of Discovery troupe in 1806 on their way home to St. Louis. Fearing a swift reprisal, Lewis had ridden hard from the Two Medicine area where they had killed two Blackfeet, an episode that would severely affect relations between whites and Indians on the upper Missouri for decades.

The first main settlement along the Missouri was Fort Union, at the confluence with the Yellowstone, just outside of Montana, established in 1828. Sporadic attempts were made further up the Missouri to trade for furs, but the killing of those two braves by Lewis’s party instilled distrust of the whites by the Blackfeet, so their success was always limited and short-lived.

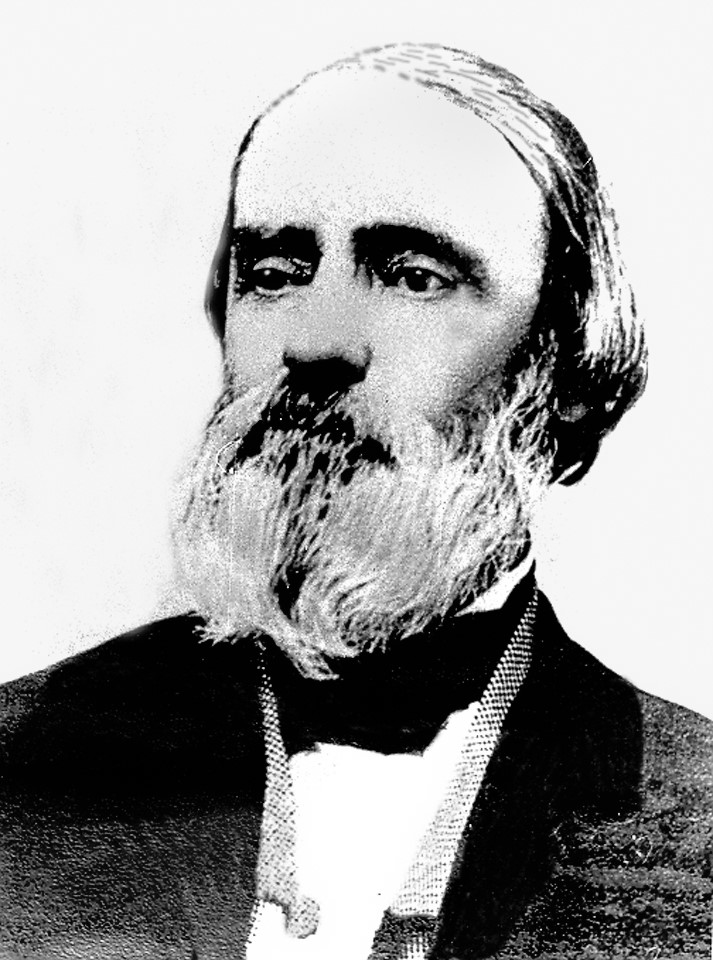

Enter Alexander Culbertson, the most influential person in the establishment and development of Fort Benton. Culbertson joined the American Fur Company in 1829 and soon became the principal trader with the Blackfeet. His wife, Natawista, was of the Canadian Blackfoot Blood Band, which gave Culbertson a great advantage in building trust with area tribes.

In 1834, Culbertson took over the Company’s fledgling trading post, Fort McKenzie, built two years earlier, a little downstream of the future Fort Benton site. In the spring, keelboats would come upriver from Fort Union with supplies and would take the season’s take of pelts and hides back down in the fall before the river froze. Under Culbertson trading flourished and he remained in charge there until 1841.

Culbertson’s replacements were not so reputable and ended up massacring a number of Blackfeet traders in January, 1842. Knowing the Blackfeet would come for revenge, they immediately abandoned the fort, running down river, leaving Fort McKenzie to be burned to the ground by the Blackfeet. Needless to say, trade on the upper Missouri suffered a major setback.

A few years later, in 1845, Culbertson returned to make peace with the Blackfeet. His apology for the massacre was accepted and trade resumed immediately. He constructed a fort three miles upstream of present-day Fort Benton. By 1847, he relocated the fort downstream to its final location which he later named “Fort Benton,” after a Missouri senator, Thomas Hart Benton, who was instrumental in smoothing some financial issues between the American Fur Company and the federal government. Unlike the coming and going of the other, failed trading forts, this one stuck.

In 1855 Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens negotiated and signed a treaty with the Blackfeet Nation at Fort Benton. This resulted in the first Blackfeet Agency being located there, meaning there was a regular flow of Blackfeet into Fort Benton. As with other settlements in the West, relations between the Indians and the whites were not always cordial and there were frequent confrontations, often with tragic consequences on both sides. The Agency was relocated in 1869.

For over 15 years, Fort Benton was the premier trading post in Blackfeet Country. By the time the fort was built, however, the fur trade was already in decline, but the trade in buffalo robes was really taking off. Over the ensuing years, hundreds of thousands of buffalo robes flowed through Fort Benton and down the river. As for Culbertson and his Blackfoot wife, they “retired” in 1861 and left for Illinois with a nest egg of more than $400,000— just before the next big boom hit Fort Benton.

While the buffalo robe trade remained robust for many more years, keeping the keelboat traffic up and down the river busy, big changes were on the horizon. Major events converged to seal Fort Benton’s prominent role in the development of the Northwest.

In 1860, John Mullan finished his famous road, which ran the 624 miles from Fort Benton to Fort Walla Walla. Ostensibly, the road was meant for military use, but was rarely used as such. However, it did provide easier access to the Northwest than the more southern Oregon Trail. Settlers headed to Oregon and Washington Territories now came through Fort Benton on their way west.

Also in that year the first steamboats made it all the way to Fort Benton, first the Chippewa, and later the Key West. At high water, Fort Benton marked the furthest steamboats could make it up the Missouri, making it the furthest inland port in the country at about 2,400 miles from St. Louis and 3,500 miles from New Orleans. The stage was now set for Fort Benton’s next chapter.

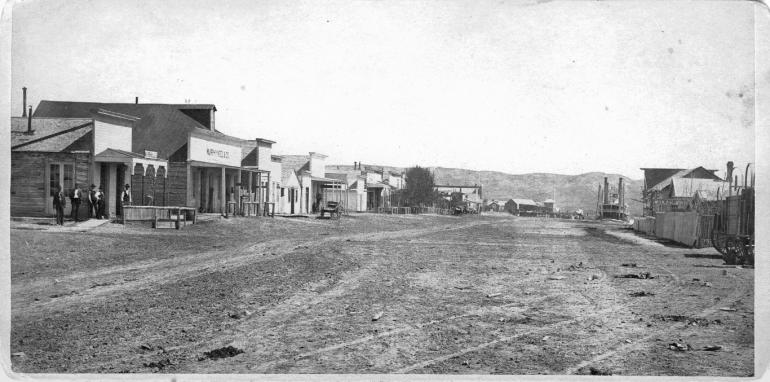

At this time, Fort Benton consisted mainly of the trading post. No real development had taken place outside the fort. 1862 changed all that. With gold discoveries at Benetesee’s Creek (now called Gold Creek) near Deer Lodge and, even more prominently, at Grasshopper Creek (Bannack), the rush was on—and they came by the thousands. Would-be miners crowded onto the steamboats, came up the Missouri River to Fort Benton and then ventured overland to the gold camps of western Montana.

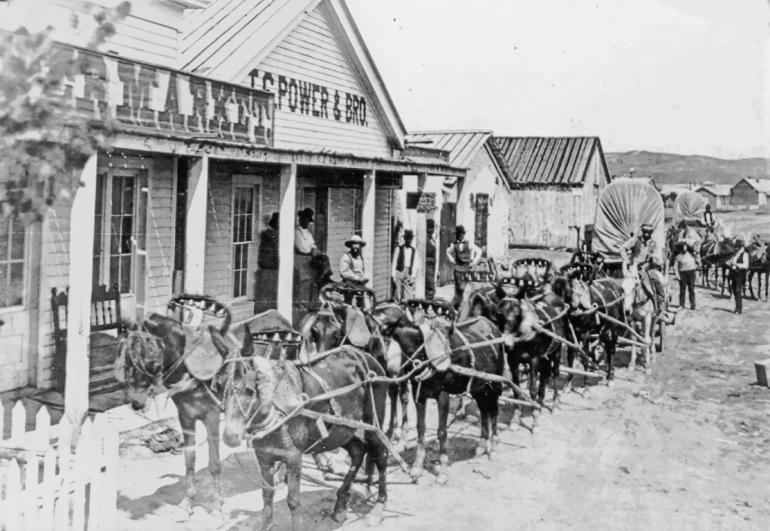

All of a sudden, there were millions to be made from the gold boom. In response, mercantiles, bars, gambling houses and brothels sprung up along the levee on the flats near the fort to feed on the new traffic. With miners arriving in the spring then leaving in the winter, the Front Street establishments got two shots at making sure men left Fort Benton a little “lighter” than they arrived. Supplies destined for the gold fields flowed d upstream on the new steamboat fleet and stacked on the levee. Some accounts describe mountains of goods stacked so high that only the tops of the steamboat smokestacks could be seen. Eventually, it was all hauled off by “bull” teams headed south to the gold fields, using Mullan’s road for the first part of the journey.

As was often the case in the West, people moved in well before the establishment of any formal law and order. These were the years of the Civil War, so there was no military until 1869. Like many other boomtowns across the West, violence was waiting just below the surface, boiling up at a moment’s notice. Vigilante groups were formed to try and establish some semblance of peace, but Fort Benton still maintained the reputation of being the most lawless and bloodiest town in the West.

Fort Benton attracted the rich and famous, would-be miners, bank robbers and killers, merchants and gamblers, missionaries, governors (one who fell overboard drunk and drowned)—all with no questions asked. Even Frank and Jesse James spent time in Fort Benton. Bannack was not the only Montana town to hang its sheriff. A man by the name of Billy Hensel showed up in Fort Benton from Helena after killing a Chinese woman there, and quickly became its self-proclaimed marshal. Mysteriously, the rate of muggings and robberies all of a sudden shot up. When his own vigilante group fingered him as the culprit, they promptly strung him up with his own rope. One gets the feeling that being an undertaker in Fort Benton during the gold rush days would have been a pretty lucrative job.

With the gold boom in full swing, river traffic only slowed when the water level dropped too low for the steamboats. Goods came in, gold went out. During 1867 and 1868, at the height of placer mining, over $24 million in gold went down river on the steamboats. Riverboat profits were astronomical. A single steamboat could realize annual profits of $40,000–$100,000 for the down river gold shipments. During these peak years, as many as 60 steamboat trips per year were made to Fort Benton. Everyone was out for a “piece of the action.” By 1870, though, the placer mines began to play out and people started looking to move on to the next bonanza. Traffic on the river slowed to a trickle—just a few per year. After the gold boom, things did not look too good for Fort Benton, and many businesses along the levee closed. It could have easily become another boom-bust ghost town. But this resilient, resourceful community had one more ace up its sleeve.

Until the Canadians also built their railway across their prairies, the cheapest way to get goods to their western frontier was upriver through Fort Benton. Not being a community to turn its back on the possibility of quick riches (ethics notwithstanding), bull and mule trains headed north out of Fort Benton up the “Whoop-Up Trail” into Canada. For the first five years, they were filled with illicit, watered-down rotgut whiskey that they would trade with Canadian Indians for buffalo robes, netting about 50,000 robes annually. Later, when the Mounties finally arrived to establish some law and order, these rather unscrupulous traders suddenly became very respectable traders, supplying the established Canadian outposts with the legitimate goods they needed. Since the cost of bringing goods in through Fort Benton was substantially less than for the overland route used by Canada’s Hudson’s Bay Company, they were able to consistently undercut them for these lucrative Canadian government contracts. River traffic picked up again, as well. The later 1870s saw 25–50 steamboat arrivals per year with about 30% of that freight shipped up north.

By 1887 the railroad finally arrived and it was the death knell for the steamboats. Ironically, the railroad was built, in part, with supplies hauled up river by the steamboats. Cattle ranches began to spring up to help sustain the town, with their cattle being shipped to Chicago on the train. But, as Fort Benton quietly slipped into the 20th century, precious little was left of its rowdy past.

The “Birthplace of Montana” was recognized as a National Historic Landmark in 1965 for its importance to Western Expansion during the last half of the 19th century.

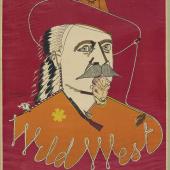

Fort Benton published a book in 1998 called Historical Signs of Fort Benton, with this picture on the cover. I scanned the inside of the book which said The Cover, The following is a documentary about the cover picture originally produced by John Mix Stanley in 1853, but was not able to paste it in this comment.

- Reply

Permalink