Buffalo Bill's Last Tour of Montana, 1914

In 1914, Buffalo Bill performed his last tour in Montana.

At 68, Buffalo Bill still stood tall in the saddle. There was little sign that he was diminished in any way.

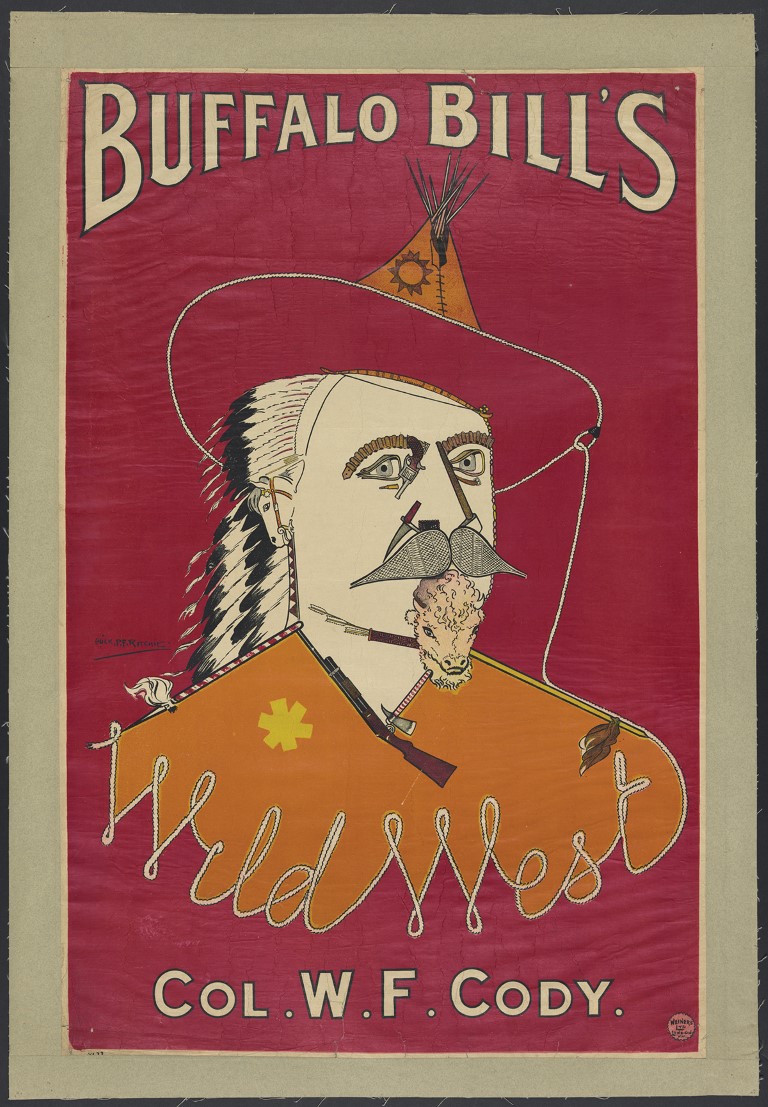

Of course, if you saw him up close you might have to admit there were wrinkles. Or if you were privileged enough to see him at home, you’d have known he was bald. At his shows, however, and on the thousands and thousands of objects bearing his image, like his own posters or the covers of innumerable dime novels like Buffalo Bill among the Comanches; or, Loud Thunder’s Last Ride, he would always don his trademark long hair.

After all, who could blame him for being a little vain? It was his job to appear in front of people—sometimes 20,000 people—and they’d come to expect an idol.

But it had been a long, long time since he had done the things that were portrayed, though through a glass darkly, in those dime novels.

It had been 38 years since his oft-recounted duel with the young Heova’ehe, or Yellow Hair (often mistranslated as Yellow Hand), in the Battle of Warbonnet Creek. He’d won that duel, though it’d been close, and scalped the Cheyenne warrior himself. Sixteen years before that, while in the Pony Express, he’d made a 76-mile ride on the Mormon Trail that had secured his place in legend.

Or so he claimed; many modern historians point out that the actual distance was twenty-something miles. Still others don’t think he made the ride at all. For that matter, on the subject of Yellow Hand, Bill himself later said, “Bunk! Pure bunk! For all I know Yellow Hand died of old age.”

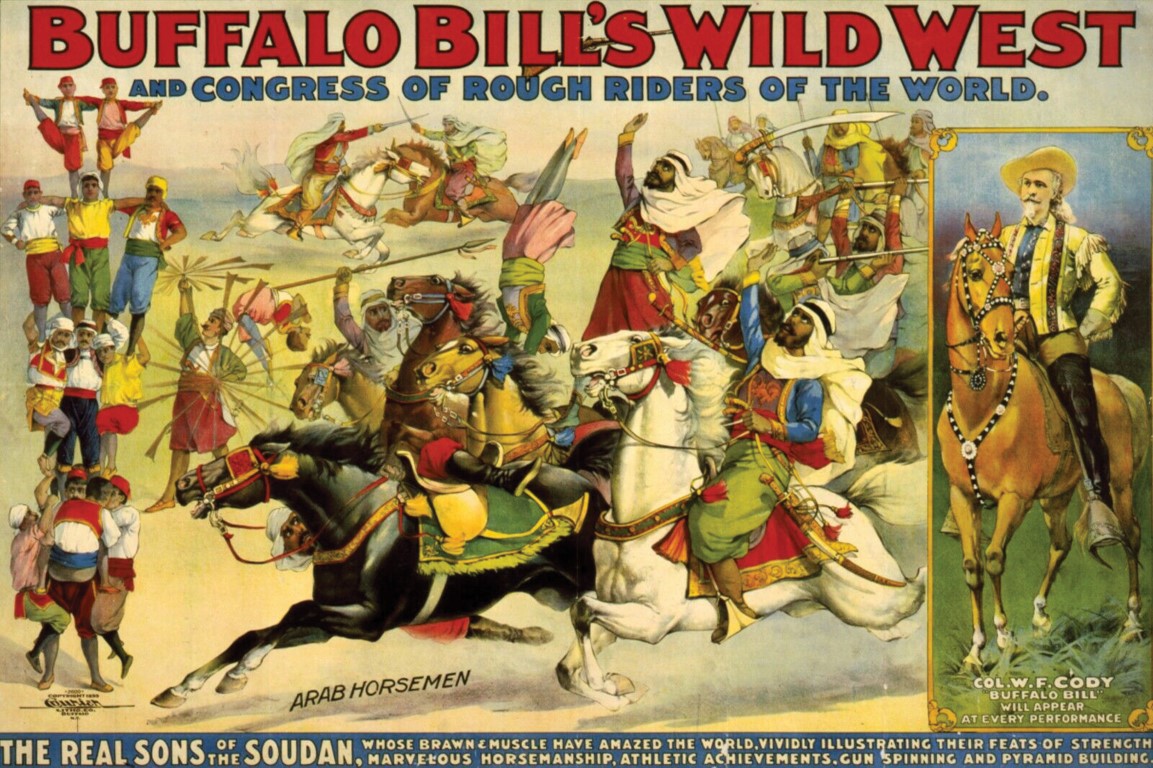

It was indisputable, however, that he had started and been the founder and face of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, later the Congress of Rough Riders of the World, under the banner of which he had traveled all over the world.

They had performed in every town in England that could support them, from Aldershot to York, and with many performances in London, including for the Queen herself, who Buffalo Bill gallantly saluted from the arena as most of the crowned heads of Europe watched on.

While at the 1883 World’s Fair in Chicago, he had put on such a good show, positioned just outside the gates, that there were some, no doubt traveling from far-flung ruralities, who arrived via train, saw the Wild West show and left thinking they had seen the whole World’s Fair, evidently satisfied.

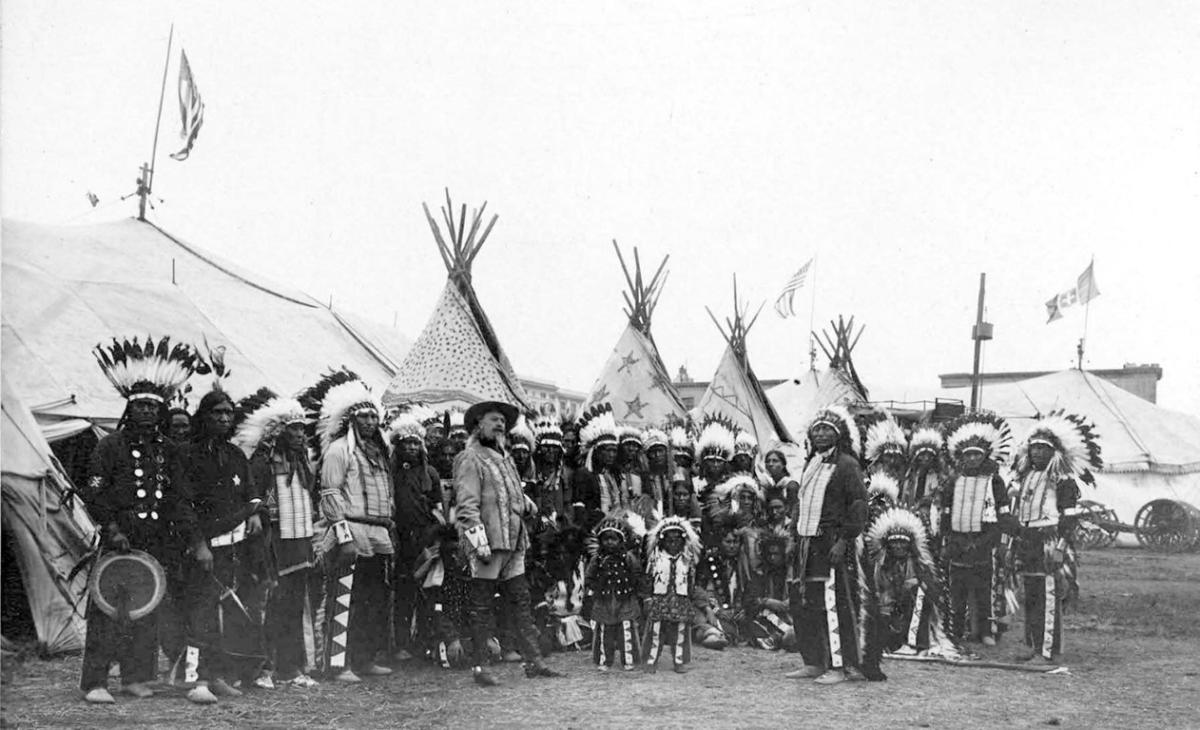

He had employed—and befriended—Sitting Bull. He had kissed the tender porcelain skin of pretty women’s hands the world over. He’d shook the hands of senators, presidents, potentates, artists, chiefs, and more recently, movie stars. The Wild West (the show, not the era) had been big. Nearly as big as its namesake, which was slipping into history even as his show crisscrossed Europe.

At its height, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West would, in the course of one week, use up:

“Beef 5,694 pounds; veal 1,259 pounds; mutton 750 pounds; pork 966 pounds; bacon 350 pounds; ham 410 pounds; chicken 820 pounds; bread 2,100 loaves; milk 3,260 quarts; ice 10 tons; potatoes 31 barrels; cabbage 7 barrels... Worcestershire sauce 15 gallons; mustard 6 gallons; powdered mustard 15 pounds... pig’s feet 1 barrel; flour 4 barrels; cornmeal 200 pounds; syrup 10 gallons; and pies 500.”

Somehow, despite the colossal expenses, Bill’s propensity for drink, and some questionable business decisions, the Wild West show had still managed to make enough money to make it the rival, and very possibly the usurper, of Barnum’s claim to be the “greatest showman on earth.”

In the intervening years, it had to be admitted, his star had been dimmed somewhat by a scandalously public almost-divorce that had shocked newspaper readers. He libellously claimed his wife, Louisa Cody, was poisoning him.

She made the much less ridiculous claim that he had cheated on her. He had been admired by women everywhere he went; certainly he had given in to temptation a few times.

But by 1914, all of that was behind him. He had even, improbably, reconciled with the supposed poisoner. They’d lost three children over the course of their marriage, and they stood to gain more by staying together than by separating. She now traveled with him, and together they treasured the simple comfort of familiarity and mutual understanding.

As Louisa and Bill watched Montana’s prairies and mountains roll by from the window of their train car, they must have thought that here was a place that, like the town named after him in Wyoming, was still at least a little wild. Montana, too, was still sparsely electrified, and resembled more than most a picture postcard of a vanishing era. They would have seen elk and moose drinking river water from his train car, and eagles circling wolf kills. They would not, however, have seen any bison; Bill had staked a good part of his legend on helping to reduce their numbers.

As Bill smoked cigars and talked with Louisa, he prepared to greet the crowds at Great Falls in June, go up into Canada and come back down to Kalispell in July. Then the most sustained sequence of Montana shows would begin in early August, with shows daily in Missoula, Helena, Lewistown and Billings, and with two in Butte. At each stop, he would parade through the town, clad in his trademark duds. In every case, there were plenty of folks gathered to see him, but he could not have helped but notice that Billings or Missoula or even the great city of Butte, on their best day, couldn’t exactly muster a throng, such as massed to see him in London or Paris.

Cody never came to Montana with his original Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. The first year one of his shows played in Butte was 1908. On that occasion, he rode with the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Far East, commonly known as the “Two Bills Show.” Since then, the Wild West had gone bankrupt, and a series of deals with rivals and competitors reduced him to appearing with the Sells Floto Circus as “the far-famed Col. Wm. F. Cody, Himself.”

Cody wasn’t too impressed with the Sells Floto Circus, complaining of their dirty tents and mouse-eaten, damp ropes. Yet, buffered from the conditions of the circus by his private train car and private valet, he was significantly more bothered by a bad deal he’d made. Henry Tammen, the deviously ruthless owner of the Sells-Floto Circus, had loaned Cody $20,000. The fine wording of that agreement apparently gave Tammen ownership over the Wild West, as well as Buffalo Bill’s name and image. Cody had found out that he was about to be absorbed by the Sells Floto Circus from a Denver newspaper, the Evening Post, which Tammen owned.

Why Cody allowed himself to be involved in such a terrible deal is puzzling, but he was in tremendous debt. He needed the $20,000 badly and probably wasn’t considering what it may cost him—namely, the rights to Buffalo Bill.

The details of the deal were that Bill was to receive $100 a day, which was no mean wage for the time but far less than the $3,000 a day Tammen drew. Cody was also to have 40% of the profits over Tammen’s $3,000, but rarely did any single show’s box office exceed that threshold. The next year, Cody demanded that they renegotiate that part of the contract, but somehow Tammen fleeced him again. During the next season, which did not tour Montana, Cody would only make 40% of profits over $3,100. Given the freak rainstorms and low ticket sales of what author Robert A. Carter called a “nightmare season,” Cody didn’t make much more than his per diem. Cody threatened to kill Tammen. That would be the last season Cody would ride for the Sells Floto Circus.

For now, Cody was required to ride out on his horse to introduce in the show, but was permitted to ride a carriage in the promotional parades, in which he was also contractually required to participate. But he didn’t take part in the Indian attack on the stagecoach anymore, and only sometimes shot glass balls with his rifle. Mostly he was symbolic, standing in, as he ever did, for something essentially both Western and uniquely American, the pursuit of progress accompanied by a nostalgia for the lost wilderness. In this capacity, he was also expected to shake hands and greet with local reporters, mayors, and aldermen.

He was still handsome in a way that even time and illness couldn’t diminish. His looks, which had inspired a poem by an anonymous English woman who, apparently speaking for much of the female population of Victoria’s kingdom, had called him “[n]ature’s perfected touch in form and grace.” Some English newspapers had wrung their hands about the relative invirility of Britain’s males in comparison with the great Buffalo Bill himself.

Now, of course, he was thinner in the cheeks. His famous locks, so much a part of his image, were also thinning, so he eventually took to wearing a toupee under his hat. “Once,” Cody’s biographer Robert Carter writes, “as he swept off his hat in his trademark salute to his audience, the toupee came off as well. He swore he would never wear it again, but he did.” Neither was the horse ideal; his prostate gave him trouble, and it was painful to ride a mount.

For all that, the Sells Floto bandmaster Karl King, who remembered him keeping “pretty much to himself in his private dressing tent,” said the old scout “had a certain amount of dignity about him I admired,” and that, despite his pain, Cody “still looked wonderful on a horse... In other words, I liked the old boy.”

Cody, along with Wyatt Earp, who lived until 1929, and Mark Twain, who lived until 1910, had achieved the bittersweet accomplishment of outliving the period with which he had become synonymous. The 20th century didn’t suit him as well as the 19th. Sitting Bull might have done the same, had he not been killed by Tribal Police sent by the government to make sure he didn’t join the Ghost Dance. But there was one thing that Sitting Bull and Bill now shared: they both had the odd experience of playing out, nightly, both their greatest victory and their most crushing defeat at once, for the entertainment of paying audiences. Time had pulled the same trick on Bill as it had on Sitting Bull. For this wasn’t the Wild West, or the Congress of Rough Riders. It wasn’t even Barnum and Bailey.

Despite boasting 11 acres of “waterpoof tents” and “new patent seats,” as well as the alluring presence of “Zora, bravest woman in the world,” who was “lithe as a willow, straight as a spear, the figure of a Juno” according to an ad in a Denver newspaper, the most the banner for the Sells Floto Circus could ever claim was “The Second Largest Show in the World.”

All of which is not to say that we should pity the Buffalo Bill who found himself looking out of his train car windows and thinking about the past that summer of 1914 in Montana. If William Cody was in decline that year, we only notice it so acutely because he had ascended to such a great height in the first place.

Larry McMurtry writes that Buffalo Bill was the most famous man in the world, but that may be putting it too lightly. Fame can be an ephemeral thing, here today and gone tomorrow. Fame is something you get for winning American Idol or starring in a Lifetime TV movie. What Bill achieved, and which survives long beyond his death two and a half years later in 1917, was to become a mythical figure.

What more could he have done? Been president? Emperor? If he’d been born a few thousand years earlier in Thebes, he might have struck it even richer and become a god, but as it was, he couldn’t have been too concerned that his legacy hadn’t been secured.

Or could it be that his mind wasn’t on his legacy in those last years? Maybe he missed his children and treasured his wife’s company again. Admittedly, he still had ideas he thought might make him rich, to regain the fortune which had withered, even unto his last months. As Robert Carter writes, “[h]e still talked grandly of new moneymaking schemes—‘I am climbing toward another fortune’—but there was no question that the old scout was nearing the end of a long and epic journey.”

He toured in 1916 with the 101 Ranch in Texas, but by the end of the season he had to be helped onto his horse, wincing in pain until he was in view of his audience, chin high and chest out as soon as they could see him.

Finally, he could not ride a horse at all. Near the end, Dr. W. W. Crook saw him and wrote that “the Colonel shows flashes of old time fire, telling his friends he soon will go on the road with a new show, bigger and better than ever. But it is evident his mind is wandering.”

Some accounts say that when he learned he had 36 hours to live, he called in his friend and told him to forget about it, let’s play some cards. Biographer Louis S. Warren writes that Cody’s nephew reported the old man “returned in his mind to his private railroad car,” smoking, reading the newspaper, and thinking himself somewhere between shows, on this continent or another.

He might have imagined a landscape traveling by his window, on that final trip, perhaps one that was wild and untouched, except by the presence of a track stretching on and on into ever more virgin territories, unmapped and maybe unmappable, until it dissolved into the horizon, where it met a big, blue, cloudless sky.

- Reply

Permalink