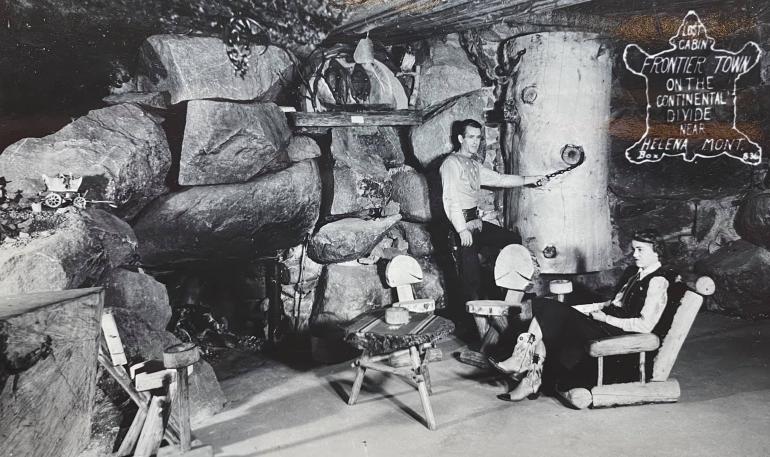

Remembering John Quigley's Frontier Town

Courtesy of Taegan Walker

"On a winter day in 1947 John Quigley, by strength and awkwardness and a knowledge of leverage, set a boulder on the Continental Divide just above Helena, Montana, and named it Frontier Town."

So begins A. B. Guthrie Jr.'s "One Man's Folly."

In 1954, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Guthrie Jr., author of The Big Sky, The Way West, and the screenwriter of Shane, was hanging out with his buddy, Montana movie star George Montgomery. Guthrie was in Helena for a Pacific Northwest history conference, and Montgomery insisted that Guthrie see Frontier Town, a one-of-a-kind attraction perched atop the Continental Divide. There, amidst the 43 rooms of hand-built, authentic Western town complete with fort, chapel, jail, museum, cabins, gift shop, a large dining hall that seated as many as 300, and a large bar constructed out of a single mammoth piece of wood, whatever Guthrie's expectations had been, they were exceeded.

"You approach Frontier Town as you would approach an old-time fort. It fronts you with blockhouses and palisades and strong swinging gates... end to end the logs would reach twenty-five miles," he wrote with admiration in "One Man's Folly."

In short, "it's wonderful," as he told the Helena Independent. "I'll never go past that intersection without stopping."

That intersection, by the way, encountered some controversy, because in the 1950s, thousands of drivers along Highway 12 were introduced to Frontier Town by an astonishing tableau: a big metal grizzly attacking a robotic dog and his prospector-owner. But before they saw it, they heard it, a four- or five-second audio loop of a dog barking that echoed through the Rockies. It was so loud that the Montana Highway Commission and the Bureau of Public Roads fought to have it removed.

Those official bodies notwithstanding, no one could resist the statue, in which the dog appeared to jump up and bravely defend his master. History does not record what Guthrie thought of the mechanical dance of the grizzly and pup as he and Montgomery turned onto the drive that led to Frontier Town proper. Maybe he thought it was a bit of kitsch, the kind of thing you saw all over the country at the time, and which in particular dotted Route 66. But when he saw Frontier Town itself, he was fairly gobsmacked.

The whole thing had been built by John Quigley and a couple of old-timers he employed. Quigley also designed it himself, and even spent winters carving chairs and furniture. It opened in 1948, and every year after the tourist season had lulled Quigley went about constructing new buildings and perfecting existing ones.

Guthrie loved the place so much he would write a short essay to be featured in a pamphlet for Frontier Town. So, for that matter, did the great K. Ross Toole, Treasure State historian, and writer of "Montana: An Uncommon Land," who wrote of the place that it "stands apart -- unique, fascinating, and with a pervasive kind of warmth about it. There will never be another place like it."

In his piece, Guthrie compared Quigley to pioneering spirits like Jim Bridger as well as monolith builders like the one-time residents of Easter Island. Quigley, Guthrie pointed out, had "tugged and lifted and dragged from the country roundabout boulders weighing from five to ten tons and set them one on another. For the most part his only aids were a pry pole and a small pickup truck equipped with a winch." But on Easter Island, he pointed out, "scores of men -- not one man -- had to struggle with weights."

Quigley constructed his buildings with near-total authenticity in mind -- so total, as a matter of fact, that he even fastened the logs with wooden pegs instead of nails. As Guthrie observed, "The result: probably the best representation of pioneer log construction in all North America."

Quigley's reach always exceeded his grasp. As Guthrie wrote, "none of these things, in part or in whole, were enough" for the enterprising latter-day pioneer. To imbibers, the crowning achievement of Frontier Town was the bar in the saloon, made of a single fifty-foot-long slice of Douglas fir and weighing over six tons. Quigley had used a chainsaw to split the titanic log himself during one miserable winter day when it was 20 degrees below zero. Then he spent some 300 hours carving elk and other Western scenes into the bar.

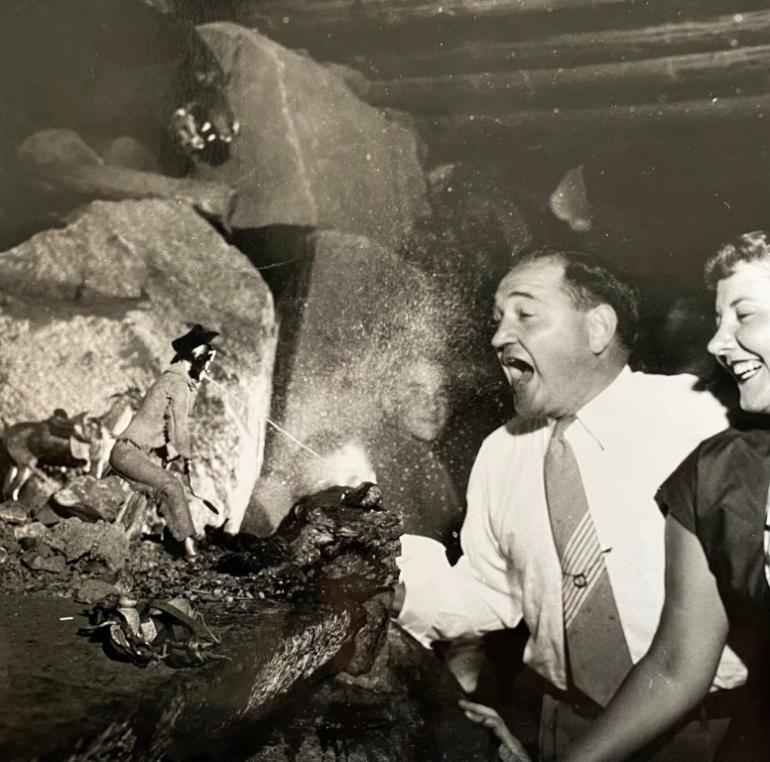

The scene behind the bar held many delightful surprises, like this "real" spitting cowboy. Courtesy of Taegan Walker.

Behind the bar was a scene that, like the grizzly and dog engaged in eternal tete-a-tete outside, was mechanically automated.

Guthrie writes, "He devised animated miniatures against a diorama self-devised, too. An eagle flies back of the bar. A stagecoach runs. An Indian sends up smoke signals of actual smoke. Indians and soldiers fight, their guns smoking, too. Over a cliff tumble scared buffalo. And lifesize on the back bar is a black bear. It broke in one night, and John Quigley reluctantly shot it. The taxidermist estimated its weight at five hundred pounds, big for a black."

When someone ordered a whiskey ditch at the bar, the "ditch" part was almost literal: the water was collected from a small spring running through the scene in between small trees (cut from the very tops of junipers and then treated with glycerine and formaldehyde). Finally, every seat at the bar was an authentic saddle, which Quigley quipped were the most expensive bar stools in the Rocky Mountain West, though maybe not the most comfortable.

John Quigley's favorite was the beautiful chapel, which he judged "our nicest building. Constructed wholly out of native logs and stone, the non-denominational church had a large picture window that looked North across the valley, a choir loft, and could seat fifty. Many Montanans and folks from elsewhere were married in that chapel.”

Quigley didn't just build, he collected. His trove of Western Americana and real regional antiques was so vast that the Montana Historical Society would sometimes trade artifacts with the Frontier Town collection for mutual benefit. The Frontier Town cache included, in Guthrie's words, "[g]old samples, flake, and wheat and quartz. Old guns. Frontier carriages. Music boxes. Outdated drugs. Ox yokes. Chamber pots. Ledgers and etchings. Chinese gold scales. Indian clothing and artifacts. And, of all things, picnic pants. All are of a time and a place, significant of the Great Plains and Northern Rocky Mountain frontier."

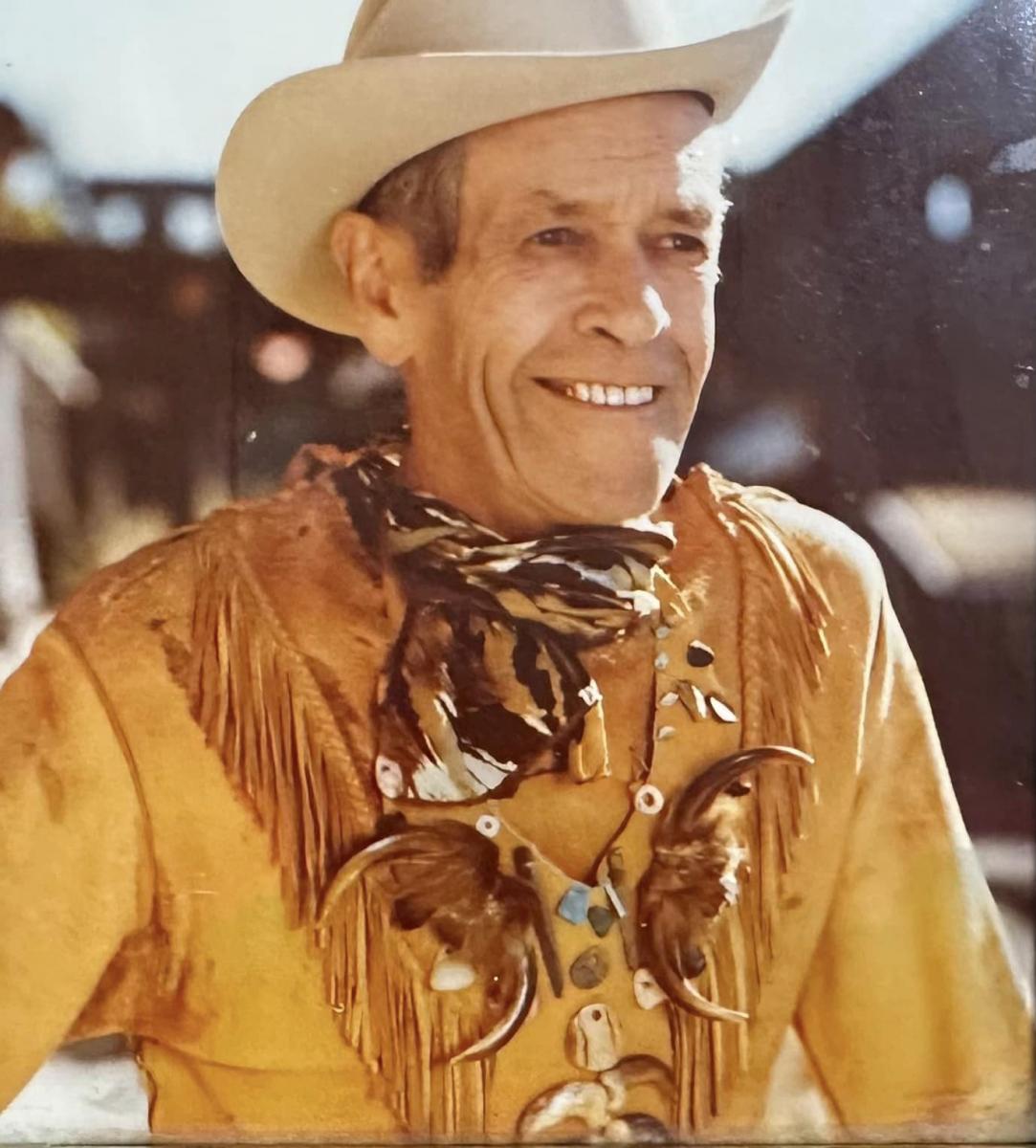

The remarkable Quigley worked hard until his death in 1979, but his family kept Frontier Town open until it was bought and sold again. As of this writing, the property is currently for sale for $1.7M and stands as the private residence of the current owner, inaccessible to visitors. Judging by the success and frequent engagement on "John Quigley's Frontier Town, Montana USA," the Facebook group (run by Quigley's granddaughter Taegan) devoted to memorializing Quigley and his family's accomplishments, on which commenters often share memories of the good old days, there are many in the state and outside of it, too, who would like to see Frontier Town as it was again and restored to the Quigley family. Taegan is actively trying to buy Frontier Town back. We wish her luck in that endeavor.

In truth, even if all we have are memories of Frontier Town, it's still a rich inheritance.

What are we, as Montanans, to make of Frontier Town?

It is a bona fide triumph of "outsider architecture," a fancy art term for when someone whom the academic or artistic world considers "naive" manages to create something amazing without their help. For instance, the Corn Palace in South Dakota, the Watts Towers in Los Angeles, or the cave city of Idaho's Dugout Dave before it was destroyed by an overzealous Bureau of Land Management.

But this one was built by a maverick, not an outsider. A pioneer.

You could see it as a remarkable, if anachronistic, example of the species of hard work and invention that characterized the pioneers. If you were lucky enough to have been there, you might remember it as a place where joyful weddings were hosted, where good liquor flowed freely in what was one of the coolest bars ever, or, if you visited as a kid, you might even have begged for one of the fiendishly tempting souvenirs sold in the gift shop. It was all of those things and many more.

As Guthrie writes, concluding his essay on Quigley and his Western dream, "[n]ot bad for a crazy fool who built on one rock. True to a time and a place. And it was built by one man."

Leave a Comment Here