Rare and Elusive Wolverines

Fine snow streaked the air, riding sideways on a gale, in early March 2006. Biologist Rick Yates led the way, breaking trail on skis through the powder. Great cliffs striped with avalanche tracks rose on all sides. Somewhere higher up among the clouds stretched the icefields that gave this valley—Many Glacier—its name. We crossed two frozen lakes and finally passed into an old-growth spruce forest that took the edge off the storm. Beneath the branches, half-buried in snow, stood a large box made of logs six to eight inches thick. It looked a little like a scaled-down cabin. But it was a trap, and there was a wolverine inside.

The animal had entered during the night. We knew from its radio frequency that this was M1: M for male, Number 1 because he had been the first wolverine caught and radio-tagged during a groundbreaking study of the species underway here in Glacier National Park, Montana. Sometimes the researchers called him Piegan instead, after a 9,220-foot mountain at the head of the valley. To me, he was Big Daddy, constantly patrolling a huge territory that straddled the Continental Divide near the heart of the park. His domain overlapped those of several females, and he had bred with at least three of them over the years while successfully keeping rivals at bay.

We paused a short distance from the trap to listen. M1 was silent. Predictably, he began to give off warning growls as we drew nearer. They rumbled deep and long with a force that made you think a much larger predator lay waiting inside, something more on the order of a Siberian tiger —or possibly a velociraptor. I lifted the box’s heavy lid an inch or two to peer in. The inside of the front wall underneath was freshly gouged and splintered, its logs growing thin under Big Daddy’s assault. Raising the lid another notch, I could finally make him out as a dense shadow toward the rear of the trap. Wolverines have dark brownish eyes, but in the light from my flashlight those orbs reflected an eerie blue-green color that glowed like plutonium, surrounded by the rising steam from his breath. The next things I saw were white claws and teeth and stringers of spit all flying at me with a roar before I dropped the lid shut and sprang back.

Inside the trap, the roaring and growling continued—wolverine for “Hope you won’t be needing your face for anything, Tame Boy, because I’m going to take it off next time!”—followed by the sound of more wood being ripped apart. Given a few more hours, M1 would have an escape hole torn through the mini-log cabin. From time to time, the tips of his claws poked out just above the uppermost log of the front wall while he rammed his head against the lid. He was trying to shove the thing upward, though the ice-encrusted logs that formed the top of the box must have weighed 100 pounds.

I looked round at the trees and the snow swirls beyond and shook my head, thinking of my long-ago vow to steer clear of these creatures. Having joined the Glacier Wolverine Project in 2004, I was going into my third straight year of breaking that vow in just about every way it could possibly be broken. No regrets. These animals’ off-the-charts strength and survival skills had become a source of inspiration for me by now. Even so, I was never going to get used to dealing with the intensity of a wolverine when it’s up close and cornered. Nobody did.

Still fairly widespread in the far North, Gulo gulo was also common across northern states from Washington to Montana during the 19th century and occasionally reported from the Great Lakes to New England. Its range continued south along the Pacific Coast range and Sierras far into California and all the way down the Rockies into Colorado and New Mexico. Today, the wolverines of the Lower 48 are confined to a few remote parts of Montana, Idaho, and northern Wyoming, with perhaps a half-dozen more in Washington’s North Cascades. They total no more than 500 and more likely number just 300 or fewer. To make a point about their present status, you could cram all of them into one person’s mountainside trophy home. It would be a snarlfest, but they’d fit.

Part of the predicament for this hunter-scavenger is that it has proved so hard to find and follow that much of its existence remains a blank. The public scarcely knows what a wolverine actually is apart from cartoon versions and trappers’ yarns about the beast. Unfortunately, natural resource managers don’t have much more to go on when deciding how best to promote the species’ survival.

For example, female wolverines den deep in the snowpack from February into May. This is a central feature of their lives and absolutely critical to the population as a whole. The insulated shelters are where the females give birth and rear their young—the litter size varies from one to four, with an average of two—until they are strong enough to keep up with her. Wolverines don’t hibernate. Far from it; each mother actively hunts a large area around the den site and carries food back to the babies once they begin to eat solid food. A mother may dig several dens in succession through the late winter and spring, transferring the infants from the natal, or birth, den to different maternal, or young-rearing, dens as they grow older. She is especially likely to move her babies if she detects some sort of alarming or unfamiliar activity in the area. But what sort of places do mothers pick for a den? High slopes or low ones? Steep or gentle? Open habitats or sheltered spots? What would managers need to do to protect dens from disturbance? As with most questions about wolverine life, the answers were either vague or nonexistent.

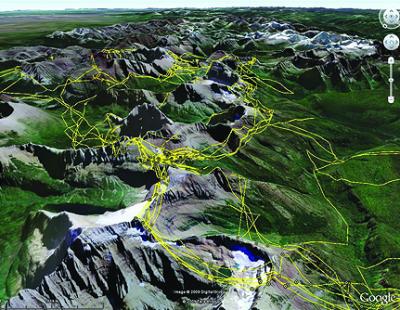

...Adding to the urgency is the current rate of climate change. What little was known about the range of wolverines made it plain that they are tied to environments with fairly heavy snowfall and cool year-round temperatures...To endure over time, though, the animals are going to need wildland corridors that guarantee individuals the freedom to roam from one chain of peaks to the next. As wolverines struggle to adapt to changing weather and shifting habitats in the warmer years to come, linkage zones running in a north-south direction may prove especially vital. Yet before ecologists can identify the best routes – the wildways that hold the most promise for keeping groups connected – many more gaps in our knowledge of the species’ natural history have to be filled in.

Jeff Copeland of the U.S. Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station was the Glacier Wolverine Project’s principal investigator, and wildlife biologist Rick Yates was the Project’s field coordinator.

Wolverines in the Rocky Mountains

To study wolverines in the field is a challenge. It often requires long days and nights trekking up a mountain to 8,000 feet in the bitterly cold Montana winter in some of the most remote areas of this country. Since wolverines have a thick muscled neck, a narrow head, and a persistent will to remove collars, researchers are forced to create alternative techniques for tracking them. Veterinarians join the field team to aid in immobilization and surgically implanting radio-transmitters. The procedure is quick, the anesthesia is reversed to wake them up post-op, and they are returned to the wild promptly.

One capture season while out in the field a wolverine revealed its unique character. We had implanted the mother and one kit and were interested in implanting the second offspring. We found the family of three by helicopter loping straight up the highest mountain face in the region. We gingerly landed the helicopter at the mountains’ ridge to head them off. Mark Pakilla, project technician, took off ahead while I post-holed my way through deep snow behind him. Unfortunately, one kit and mother wolverine had crested the mountaintop and were headed out of sight down the back side. As I began to descend the mountain’s north face, I found Mark, wolverine, and snow rolling down the steep slope. No vegetation lay in their wake except for a small tumble weed. Luckily its roots and frozen ground were enough to stop the momentum of this mammal-made snowball a few hundred yards below me. By the time I got to the site there was more red snow than white and I wondered which one was my patient. Mark had captured a juvenile wolverine with his bare hands—and he was paying the price. But it was the wrong wolverine. Telemetry told us that we had implanted this kit on a previous day and the one we wanted was running down the backside of the mountain.

The kit we had was extraordinary. Although young, this resilient animal could bound up the face of a mountain, wrestle a grown man, leaving him bleeding yet remain unscathed. He continued gracefully up the mountain to reunite with his mother and sibling. No wonder wolverines are considered the real ‘iron men’ of the animal kingdom.

~ Douglas H. Chadwick is a wildlife biologist and journalist who not-so-secretly wants to be a wolverine. Or at least to master the mountains half as well as your average Gulo gulo. Except, he says, he’d like to skip their habit of facing off with grizzlies over carcasses and trying to intimidate the bears. He has traveled the remote reaches of the globe on magazine assignments to learn about untamed creatures and ecosystems and is the author of 11 popular books. This excerpt is by permission of publisher Patagonia Books.

Leave a Comment Here