The Old Broke Rancher's Fortune Denied

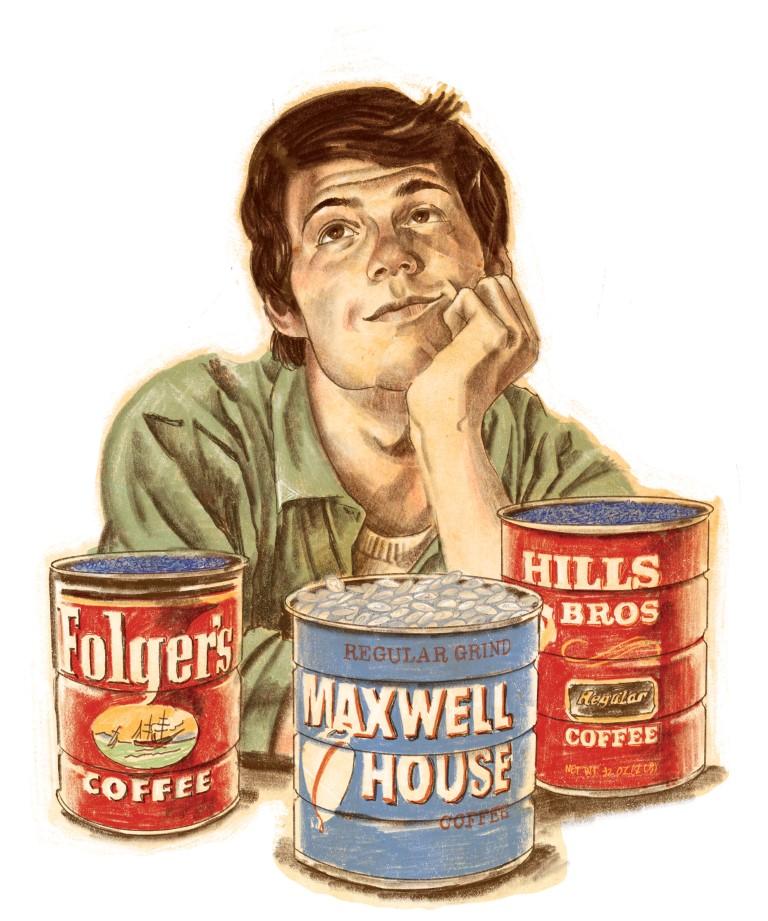

The (Young) Old Broke Rancher Contemplates His Riches. Graphic by Rob Rath.

How many of you are fortunate enough to have a younger brother? I have endured that good fortune for most of my life, and though I will readily admit that as a grown man (only slightly younger than me, an even older old man), he has some redeeming traits. He makes a fair canoe camping buddy, for one, and is passable to pleasant company on the road. But as a teenager, he was a real SOB. Loathe as I am to incriminate my own brother, I’ll tell you why.

All through the 1950s and 1960s, our family used to make an excursion out of searching for Yogo Sapphires. We would take Dad’s old GMC pickup and light out for the sapphire digs in the Little Belt Mountains.

We would camp on Yogo Creek, or, when most of the snows had melted later in the summer, on the middle fork of the Judith River, where there was still plenty of water for washing the digs. By the 1960s we even took a motorcycle; then we could explore the mountain trails far and wide around the camp.

The whole family would dig into the mountain along the Yogo dike, digging in the sand and rocks that had eroded out of the dike over millions of years previous. Then we would pack our pay dirt, back to the creek to be screened and washed. In the process, we would look for sapphires. It was hard work for kids, but mostly it was an excuse to get away for all of us.

In the process of washing the gravel, I got good at spotting the little blue stones. I would pick the glistening stones out of the wet gravel and sand, with tweezers. A day’s worth of digging, washing, sifting, and screening could net a cup full of the tiny stones. Very rarely, one would be big enough to attract the attention of Dad. Over the almost 20 years of summers digging, we probably only found a half dozen or so that were large enough to send to a gemologist or stone cutter to be made into jewelry, but I did pick up a whole lot of little stones, watch-jewel quality, enough to fill a whole coffee can. I hid that can behind the fine silverware we never used, beside another six coffee can full of silver dimes that I got from my newspaper route.

You see, the Coinage Act of 1965 was signed into law on July 23rd of that year by President Johnson. The new law eliminated silver from dimes and quarters. I’ve always been a bit libertarian, I guess, but to my 13-year-old mind it made the newly minted coins little more than slugs. And I confess that it still amazes me that all the Treasury has to do is write, “this note is legal tender, for all debts, public, and private,” and we think that it’s worth something.

That having been said, I wouldn’t want you to get me wrong. I love money, which is why I hoarded the silver dimes. I reckoned that their value in metal would someday exceed their value as currency. I was right, too—if I had those today, I’d be able to eat a steak and wash it down with a big tumbler of Johnnie Walker every night for the next six months or so. Hell, maybe I could even drink something that ain’t blended, although that might shave a month off.

Because, as you might have inferred, I never got to make any money from those hidden coffee cans full of loot, because my delightful brother, the little blessing, sold the lot of them for comic books, candy bars, and bottles of soda.

I went ballistic, nearly to orbit, when I came home from college to discover the whole kit and caboodle gone. No coins, no sapphires.

Evidently, he sold the sapphires in a single transaction, getting $20 from a local jeweler for the lot. The dimes, however, went in sticky little handfuls to the corner store, where he bought his ill-gotten sweets. He must have thought I wouldn’t notice if a few went missing here and there, but over my freshman and sophomore years of college I guess the little monster developed quite an appetite. I came home to a sad scattering of tarnished coins left out of the thousands I’d had.

My first thought was of going back and at least getting the sapphires back, but he sold them almost as soon as I’d left. And without the boy coughing up all the sugar he’d imbibed in a year or two so we could return it to the store for a refund, I wasn’t going to get those dimes back, either. So really, the only recourse for me was to punish the little brother and relish it.

When I was seven and he was two, I could have tortured him. When I was 15 and he was 10, sure. But at 19 and 13, the fun had gone out of it for me. I tried a half-nelson or two, a light punch, and that old standby the Dutch rub, but I failed to derive any pleasure in his pain. I suppose you could say I was growing up.

Besides, I figured the real enemy was the jeweler who would offer a little kid a measly $20 (although it has to be admitted that $20 went a lot farther back then) for that many yogos. So I decided to go have a talk with him.

The jeweler, whose name I will hold back to protect the innocent, listened to me explain the situation. Then he spoke.

“Your little brother comes in with all these sapphires, most of them no bigger than a speck, and I figure I could sell them for watches, but they aren’t worth much otherwise, so I asked him what he wanted for it, and he thinks a moment and says, ‘twenty bucks,’ so I got a bill out of the register and said we had a deal. I don’t know what else to tell you.”

“But you know they were worth more than that!” I protested.

“That’s called making a profit, kid. You didn’t want your brother stealing them, you should have hidden them.”

“I did hide them!”

“Not well enough.”

It did occur to me that he had a point. I had hidden them behind the good silverware with the notion of protecting them from invading thieves, but I had never considered that the breach could come from within. But it didn't make me feel any better.

“Okay,” I reasoned. “How about you just give me what it’s worth? We’ll call it even.”

“Haha,” he said. He was still saying “haha” when he opened the front door and ushered me outside. I’d like to think he spent the rest of his days looking over his shoulder in case I’d finally decided to exact my pound of flesh, but it’s more likely that he became a Congressman and enjoyed great success.

That was more than fifty years ago, but over the decades, I’ve still thought about those purloined yogos. They’ve become a sort of lynchpin in my personal mythology, a piece around which the rest rotates. The more time passes, the bigger the lost fortune. At this point, I’m fairly certain I could have bought the Taj Mahal for what all that silver and sapphire was worth. Maybe even afford a house in Bozeman!

But instead of steak and whiskey, I’m having hamburgers and Rolling Rock. It could definitely be worse, but still.

So every now and then I need to remind Neal how he ruined my whole life. To that end, I will sometimes call him at about 11 PM, just when I know he’s about to go to bed. The phone rings, and then I hear him pick up and say, “Hello?”

And then I say, “Neal, I want you to know I love you. You’re a great brother, and as time goes on I know that family is the most important thing of all.”

“Thanks, bro,” he always says, knowing what’s coming from habit.

“But I also want you to know that you’re a moron and that I might be the CEO of a Fortune 500 company if it weren’t for you, and I’d probably own three yachts and four RVs if you hadn’t ruined everything.”

“Love you too, Gary, sorry again about the damn yogos,” he usually says. And hangs up.

"Don't forget the dimes," I mutter.

Gary Shelton was born in Lewistown in 1951 and has been a rancher, a railroader, a biker, a teacher, a hippie, and a cowboy. Now he's trying his hand at writing in the earnest hope that he'll make enough at it to make a downpayment on an RV. Hell, scratch that. Enough to buy the whole RV. He can be reached at [email protected] for complaints, criticisms, and recriminations. Compliments can be sent to the same place, but we request you don't send them - it'll make his head big.

- Reply

Permalink