Jenna Caplette migrated from California to Montana in the early 1970s, first living on the Crow Indian reservation, then moving to Bozeman where she owned a downtown retail anchor for eighteen years. These days she owns Bozeman BodyTalk & Energetic Healthcare, hosts a monthly movie night, teaches and writes about many topics.

*********

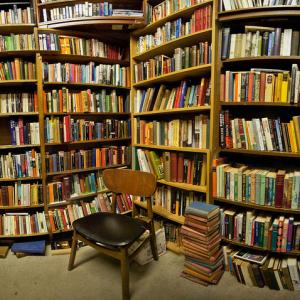

My daughter and I have a joke when we’re traveling. I’ll drive or walk by a bookstore, say, “Look, a bookstore! “ And she says, after at least twelve years of this joke,

“No Mom. No more books, You don’t need any more books.”

Need? No. Desire? Yes.

When I visit local, independent bookstores, maybe it is also somewhat about hope, the “What if?” of my own languishing novel. As if I might magically find it on the local authors shelf in one of the bookstores I visit and discover that in a parallel life I got myself moving and revised it one more time and . . .

Anyway, it was in a small bookstore in Red Lodge that I first found a novel by Wyoming author Craig Johnson, The Cold Dish. I noticed it because it had a “local author” sticker. I purchased it because it sounded like it would have a Western flavor I might enjoy -- the protagonist is the Absaroka County Sheriff. His best friend is Northern Cheyenne.

I enjoyed The Cold Dish. Eager to share it, I happily wrapped and sent it to my dad, who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. For years I had shared Tony Hillerman mysteries with my him but we’d run through the series and now when a new book did come out, one of my sisters often beat me to the purchase.

Neither of my sisters beat me to The Cold Dish, or Death Without Company, or No Kindness Goes Unpunished, nor any of the rest of the Walt Longmire series as it grew.

Last summer I noticed that Johnson would be hosted by the County Bookshelf in Bozeman. It was a sure bet I’d be going. Couldn’t wait to tell my dad about it. I found Johnson funny, insightful and articulate. My reading of his mysteries had been a private daughter-father thing for me, so it startled me to discover he had a following.

Even more surprising was the Longmire TV series based on his novels. I had no idea. I loved that Johnson was on a motorcycle tour of smaller, independent bookstores. A lot of authors get sent on book tour by publishers but only hit larger communities. Ariana Paliobagis of Bozeman’s Country Bookshelf, says that Johnson’s first visit was so much fun, as soon as they knew he had a new book coming out, they invited him back. “He has a big fan base here.”

So Johnson returned to Bozeman at the end of June. Book signings, says Paliobagis, are something that brick and mortar book stores can do that online sellers cannot. The signings build excitement and a sense of community.

Its clear many of those attending this signing are eager to share with Johnson their love of his stories and characters.

As it turns out, this was more of a pickup-truck book tour. When Johnson had gotten ready to hit the road, his motorcycle wouldn’t start. He couldn’t take the time to sort out the problem. And maybe that was a good thing because he says it has been raining since he left his home in Ucross Wyoming.

The catalyst for mystery number nine, A Serpent’s Tooth, came from a news piece. Many of his novels do. Johnson saves articles from Wyoming, Montana and South Dakota newspapers. He says he’s a “burr under a saddle-blanket writer.” The burr is a social issue he wants to take on. He matches the social issue with one of his on-reserve articles and goes from there, often spending a year in research.

He says the most outrageous stories in his books come from Sheriffs he’s visited with. He catalogues and files those away like he does the newspaper articles. Johnson found the newspaper article that inspired A Serpent’s Tooth in a South Dakota newspaper. The storyline includes a Mormon ‘lost boy.‘ Johnson says that until now he has avoided the topic of religion. With friends on the Northern Cheyenne and Crow reservations, he says in the past twenty years he has spent more time in Sweat Lodges than churches. His novels have not ducked spirituality.He says that the Northern Cheyenne and Crow have been here a couple thousand years. We newcomers to the Northern Plains, a couple hundred. He says maybe they know stuff we don’t.

Or that’s what I heard because as he talks I’m drifting and thinking how much I appreciate how he does handle that spirituality. It’s a big part of why I’ve kept reading his work. Married to a member of the Crow Nation for fifteen years, that spirituality is a big part of who I am too.

Johnson says that when he reads from his work at a book signing like this one, he’s editing, sometimes changing what is printed on the page. There’s always something that could have been different, better.

Yeah. I’ll feel that way too, as soon as I submit this piece to the Distinctly Montana Blog, think “Should have said, the point really was, and . . .”.

I remember what it was like when I was immersed in the world of my own novel. What it was like to be around authors more often, to listen to them with an intent to refine my own craft. To think of myself in any way as a novelist.

Johnson says he put The Cold Dish in a drawer for ten years. It would be a lot of work to resurrect Eagle Dreams, my historical novel. It’s languished almost as long as Johnson’s mystery did.

Maybe its time.

In the meanwhile, time to catch up on my reading. I’m still haven’t read Johnson’s Hell is Empty.

In many rural communities across Montana, the summer calendar is neatly divided by specific events: school gets out, Independence Day arrives, harvest season gets into full swing, and then before you know it, it’s time for back-to-school shopping. Fitting squarely in the middle of summer’s routine is the county fair.

In many rural communities across Montana, the summer calendar is neatly divided by specific events: school gets out, Independence Day arrives, harvest season gets into full swing, and then before you know it, it’s time for back-to-school shopping. Fitting squarely in the middle of summer’s routine is the county fair.

Over 100 watercraft took part in the Saturday leg of the 2013 Yellowstone Boat from Big Timber to Reed Point. Over the course of three days, the rafters float the Yellowstone River from Livingston, Montana to Columbus, Montana.

Over 100 watercraft took part in the Saturday leg of the 2013 Yellowstone Boat from Big Timber to Reed Point. Over the course of three days, the rafters float the Yellowstone River from Livingston, Montana to Columbus, Montana.