Montana’s Banana Belt

The Tobacco Valley

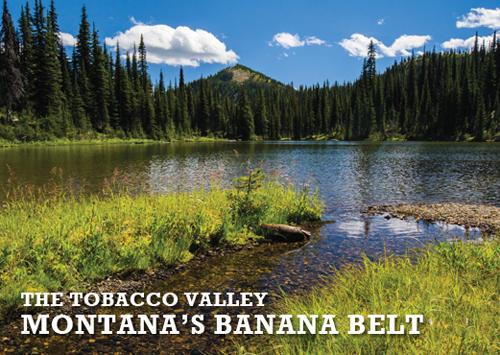

Called Montana’s “banana belt” by locals, the Tobacco Valley spans the wet Purcell Mountains to the west and the lofty peaks of Glacier National Park less than an hour to the east.

Here Montana boasts the state’s mildest weather. It’s not tropical, but it is a paradise for lovers of the outdoors and history. From a base in the thriving community of Eureka, hike the Ten Lakes Scenic Area and immerse yourself in the area’s many offerings with a fraction of the traffic. As a gateway to Montana for Canadians coming to Glacier, Montana’s Banana Belt buzzes with activity while also providing plenty of opportunities to have lakes — and huckleberries — to yourselves if you’re willing to walk.

Tobacco Valley tourists may be forgiven for thinking they’ve wandered to the east side of the state. A sea of short-grass prairie surrounded by vertiginous, fir-clad peaks, the Valley spread between the Purcells and the Whitefish Range is part of a larger geological feature called the Rocky Mountain Trench that extends from northern British Columbia into Montana. During the last ice age, the Rocky Mountain Trench glacier covered the valley under thousands of feet of ice. As it retreated, the glacier left a landscape pocked with glacier-plucked pothole lakes and ponds in addition to long, streamlined hills known as drumlins — the only large drumlin fields in Montana.

The glacier also left behind rich soil. The bands of Kootenai living in the region dug the plentiful pink- and blue-hued bitterroot for its bulbs, raised hay for ponies and grew tobacco; the tribe called the valley “The-Place-of-the-Flying-Head,” a reference to the slightly narcotic qualities of the tobacco grown there.

As productive as the prairie was for the Kootenai, it was much too dry for European settlers. In 1914, farmers, flush with enthusiasm for a proposed “Big Ditch” that would divert water from the foothills to the valley floor, leveraged their life savings into homes in the valley. When the Big Ditch ran dry a few years later, so did the homesteads.

It was not the first calamity to strike the valley. In 1924, half the population of Eureka lost its livelihood when the Eureka Lumber Company — one of the largest lumber mills in Montana — abandoned the town. On top of that, strike-it-rich schemers never discovered sought-after silver and gold. But the name “Eureka” speaks to the optimism of the valley’s residents, and today it’s experiencing a second boom, this time tourism. Eureka entrepreneurs have converted old boom-town buildings into charming businesses. And, located just south of the Canadian gateway to Glacier National Park, the valley sees a steady stream of trailers and RVs each summer. But Tobacco Valley visitors can best experience it on foot.

First, stop at the Tobacco Valley Historic Village downtown, which contains historic buildings from old villages along the Kootenai River, some of them rescuees from when construction of the Libby Dam flooded the Kootenai River valley. Wander among pioneer cabins, old Forest Service buildings, and a rail depot. Children will enjoy clambering on the old farming equipment. Like so much in the Tobacco Valley, the historic buildings are a testament to salvaging something positive from calamity.

From the Tobacco Valley Historical Village, two paths beckon. At one time part of the extension of the Great Northern Railroad from Columbia Falls to the town of Rexford, today the Kootenai Trail offers 7.5 miles of rails-to-trails recreation. Amble among joggers, dog walkers and anglers while keeping an eye out for osprey and eagles.

The product of a years-long community effort to construct a showpiece path along the Tobacco River, the Eureka River Walk makes for a great after-dinner walk or a respite from window shopping on Dewey Avenue downtown. Cottonwoods shade the two-mile, mostly paved loop; ducks and deer, not at all shy, wander amongst the riverside willows. Interpretive signs, fitness stations, and benches encourage stopping, whether for rest or exercise.

Just north of Eureka, the Dancing Prairie Preserve protects one of the last sites in Montana where the Columbian sharp-tailed grouse performed their mating dances. The Nature Conservancy purchased the parcel in 1987 in the face of alarming declines in the grouse population. The grouse’s springtime leks are now silent, but the prairie still protects a plethora of rare native prairie plants. Come mid-summer, the white blooms of the Spalding’s catchfly welcome visitors to this fragile — and increasingly threatened — habitat. Only a few hundred specimens remain in the plant’s native habitat in the Palouse Prairie of southeast Washington, northeast Oregon and west-central Idaho; Dancing Prairie Preserve boasts more than 10,000 — 90 percent of the plant’s population. Needless to say, tread lightly.

Overshadowed by its famous neighbor to the east, Glacier National Park, 40,000-acre Ten Lakes Scenic Area, just shy of the Canadian border, boasts an abundance of shallow, grass-fringed lakes suited for foot-soaking amid rocky spires and wildflowers. Proposed for Wilderness designation by the Forest Service for over 30 years, the Ten Lakes Scenic Area remains a wild island amidst a sea of timber activity. Acres of intact old-growth forest and expansive alpine meadows make for some of the best bruin habitat in western Montana. While hikers are unlikely to spot a grizzly, wildlife is plentiful in the area, including deer, moose, and the by-turns wary and gregarious grouse. Two-legged locals also revere the area for its bumper crops of huckleberries, but visitors willing to walk can easily get their fill.

On the edge of the Ten Lakes Scenic Area, Big Therriault and Little Therriault Lake Campgrounds offer gentle walks in addition to some of the best tent side views in the Northwest. Departing from Big Therriault Lake Campground, the Big Therriault Lake loop trail wanders just under two miles through prime berry-picking country. Hardy hikers can pick up the steep trail to Stahl Peak and its first-come, first-served fire lookout two miles from the lake. At Little Therriault Lake, a 1.25-mile ADA-accessible gravel path grants access to prime fishing and huckleberry picking for campers inclined to forage for their food.

Hikers interested in a daylong trek can sample a handful of picturesque lakes — with plenty of huckleberries as an appetizer — on the 10.5-mile Bluebird Basin loop. From the Bluebird Basin trailhead near Little Therriault Lake, climb through huckleberry-laden forest 1.5 miles to shallow — and aptly named — Paradise Lake. Continue around its grassy shores for another 10 minutes of trail time, bearing right at two junctions, to Bluebird Lake. Turn around here for a kid-friendly 5-mile hike. Otherwise, climb around 7,350-foot Green Mountain and descend to Wolverine Lakes. To complete the loop, continue another 2.5 miles to the Wolverine Lakes Trailhead, from which the 3.5-mile Clarence Ness trail connects back to the beginning.

* * * *

*For a related article in the Archives see “The Beautiful Bitterroot Valley” by FWP, Fall 2007.

Leave a Comment Here