The Madison Buffalo Jump

Rich in Stories and Grandeur

Artwork courtesy of Head-Smashed-In World Heritage Site

Artist Shayne Tolman

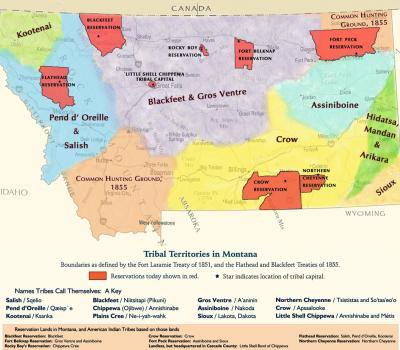

The Madison Buffalo Jump in Gallatin County is surrounded by high limestone bluffs and overlooks the Madison River Valley. Many, hikers, horseback riders, and school groups enjoy scenic beauty and panoramic views on site, while also learning to appreciate its extraordinary cultural, archaeological, and historical significance. It was used by at least fourteen different Native American tribes for communal bison hunts as far back as 2,500-3,000 years ago, continuing into the early 19th century. (See partial listing in corresponding illustrative map.)

I will always remember my first hike here and transported in time and cross-cultural understanding. The cunning, courage, and physical prowess required of the Montana tribespeople who hunted and drew their sustenance from the bison that roamed here were truly remarkable. Their sophisticated skills are nearly unimaginable by contemporary standards. Most definitely, they were not primitive or uninformed people.

Wabusk Ragged Robe, a member of the Aaninin/White Clay tribe explains,” Buffalo jumps are locations that fill me with awe and respect for all of the old ones who used them. They are a testament to the historical presence of Tribal nations and their knowledge of landscapes and buffalo behavior.”

“When I am standing at Madison Buffalo Jump,” he continues, “I am standing in the footsteps of my ancestors. The feat of utilizing a buffalo jump like this for hunting buffalo cannot be recreated. The intimate knowledge that my forefathers had of the habits and psychology of the buffalo cannot be overestimated. Using intellect and ceremony allowed Native peoples to create opportunities that would be impossible today. Their wisdom, coupled with their reverence for the buffalo, ensured successful communal hunts that fed, clothed, and sheltered them.”

Buffalo jumps were used in the late Autumn, so that tribe(s) would be able to kill and process a large quantity of meat, hides, and bones before winter arrived. The communal hunts were carefully organized in advance, infused with ceremony, and set in motion by scouts and runners. Everyone involved had to understand the topography of the land and be able to locate a herd on a gathering plateau. The enterprise also had to be nearby miles of well-placed rock cairns equipped with fresh-cut brush for prepositioned tribespeople to wave at the just the right moment to help funnel the stampeding buffalo along carefully mapped drive lines that ended in a serviceable cliff.

Next, a series of carefully orchestrated tribal ruses were used to trick and manipulate the herd into the drive lines. Taking advantage of the natural curiosity of the buffalo, cleverly-disguised hunters would patiently move near the herd, falling to the ground, jumping up in the air, imitating the sounds of buffalo calves, twisting around several times, falling again, running a short distance, and doing it all over again. Each action was punctuated by periods of calm during which the hunters would lay or stand perfectly still.

Additional hunters (i.e. the renowned buffalo runners) would position themselves downwind of the herd, but above the targeted destination. Again, the hunters acted out in fits and starts of orchestrated movements, sometimes dragging themselves along the ground. Their gyrations would eventually draw the interested buffalo toward the hunters who would slowly, over many hours, retreat toward the cliff. Once the herd began running, they would run beside the on-rushing buffalo. Not surprisingly, those buffalo runners were young men in the prime of life, who had mastered the tricks of the trade that were passed down to them across many generations. It was a strenuous, skillful, and dangerous role that earned one honors and respect with the tribe. One wrong move, a gust of wind from the wrong direction, a suspicious bleating call, a distant dog bark, a hunter showing himself at the wrong instant — the slightest miscue could send the herd fleeing off in any number of wrong directions.

The Madison Buffalo Jump is not a run-of-the mill buffalo jump. An unprecedented National Park Service study in 1962 trumpeted the “exceptional value of this classic site.” Another renowned scholar and field investigator recorded it to be “one of the best known and the most spectacular of all kill sites in Montana.” In 1964, Montana State College (MSU) experts first proposed that it be protected as a National Monument. Just last year, University of Montana Professor of Anthropology and author Doug MacDonald oversaw the most comprehensive cultural and archaeological survey of the site ever compiled. Using GPS and other new technology, he and his team concluded that they could easily spend the rest of their professional careers mapping and studying the artifacts and unique features of this special place.

Nevertheless, an on-going threat looms over the future of the Madison Buffalo Jump State Park, casting an ominous cloud of uncertainty. It raises the specter of possible closure of the park and the prospect of it being opened to grazing. Worse yet, the Montana Department of Natural Resources (DNRC), the custodian of state trust lands, could even sell it for residential development.

The crux of the problem is the cash-strapped Montana State Parks System does not receive any line item appropriation to finance operation and maintenance costs in the state budget from one year to the next, thus having to rely instead upon a $6 vehicle registration fee as its biggest source of funding. Consequently, while Fish, Wildlife, and Parks (FWP) is willing to continue to maintain the park (i.e. pay for personnel and operations), it can ill afford to pay an escalating annual leasing fee to the DNRC.

This is a spiritual place, a rare and nearby natural wonder, an extraordinary outdoor classroom, and an irreplaceable part of Montana’s cultural heritage stretching back thousands of years. The highest priority should be its preservation now and for posterity.

CORNERSTONE FOR MONTANA'S FIRST NHA

One preservation option could be for the Madison Buffalo Jump State Park to become a cornerstone for the establishment of Montana’s first national heritage area (NHA). Imagine the Cultural Crossroads of Native North America NHA grounded here in Southwest Montana, if you will. (See illustrative map showing how various places and cultural stories across 11,000 years of human history in the incomparable Montana landscape could be linked in a compelling narrative).

What is a NHA, you might ask? It is defined “as a place recognized by Congress where natural, cultural, historic, and recreational resources combine to form a cohesive, nationally-distinctive landscape arising from patterns shaped by geography.” That definition fits the Madison Buffalo Jump, in particular, and its Southwest Montana surroundings exactly. They must be locally conceived, developed, and administered by local nonprofit organizations, civic groups, other private corporations, and/or state governments.

It is also important to understand what NHAs are not. They are not units of the National Park Service (NPS), nor do they involve acquiring any type of additional federally owned or managed land. Instead, lands within heritage areas remain in private, local, or state ownership or some combination thereof. Functionally, they are voluntary partnerships among local communities, counties, states, and the NPS, wherein the NPS supports local and state conservation efforts strictly through federal recognition, seed money, and technical assistance, if so desired.

For instance: Last August 5th, the First Peoples Buffalo Jump State Park near Great Falls was designated a National Historical Landmark (NHL) by the U.S. Department of the Interior. Under this federal program, the National Park Service will now wield authority to oversee and maintain this site — comparatively a more top-down, Washington, D.C. driven approach to historic preservation than the bottom-up locally-controlled NHA approach.

****

Hope that your parents are well. Please greet them for me. They were class people and good parents.

- Reply

Permalink