The Lone Ranger of Yellowstone: Marguerite Lindsley

photos courtesy of National Park Service

Although today women make up a third of the National Park Service’s workforce, it wasn’t until 1978 that female park rangers were allowed to don the official badge or wear a proper uniform. In the 1960s, women rangers wore stewardess-style fitted jackets, tight knee-length skirts, and pillbox hats. Their role was reflected in a statement made in 1960 by the National Park Service that “women cannot be employed in certain jobs, such as Park Ranger or Seasonal Park Ranger ... in which the employee is subject to be called to fight fires, take part in rescue operations, or do other strenuous or hazardous work.”

By the 1970s, the uniform had evolved to incorporate a mini-skirt and go-go boots. Not great for scaling rock faces, fighting brush fires, or walking in deep snow. But then again, women rangers were generally only hired in roles that were seen as ‘interpretive’ or secretarial. In order for women to be given equal tasks to their male counterparts, it took an Act of Congress, a ruling by the Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and much campaigning by the few women and some of the men in the Park Service.

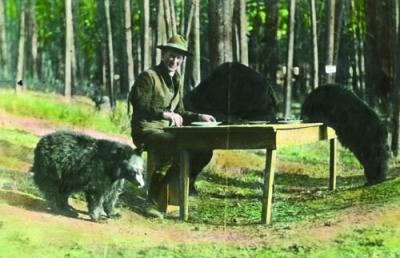

Despite their late acceptance to the role of fully-fledged Park Rangers in 1978, many women made an impact on Montana’s National Parks, especially the nation’s first designated park: Yellowstone. In the 1920s the Superintendent of Yellowstone National Park was a forward-looking man, the son of a miner from California: Horace Albright. He battled the entrenched “boy’s club” atmosphere that dominated the Park Service by hiring female employees when there was widespread animosity towards the idea. Between 1920 and 1933, Albright hired 10 women in Yellowstone and came under fire for doing so. But he was outspoken and believed in the skills and commitment to the Park Service by these women. He wrote to one of his adversaries, “Personally, I believe that in certain phases of our educational work women can do just as well or better than men.” He went on to say that he had “found most male rangers are more or less useless in the Chief Ranger’s office and I think that if we are going to keep our organization at the highest efficiency we may have to employ a few women in the organization.”

The most notable of Albright’s female employees in Yellowstone was the naturalist Marguerite “Peg” Lindsley who was born at Mammoth Hot Springs in 1901 at a time when the U.S. government still had no idea what to do with its abundant wilderness areas. During this period the Parks came under military charge. Growing up in Yellowstone, Marguerite regularly heard the sound of cannon fire and the hooves of cavalry horses along with the cry of wolves and birdsong.

The daughter of Yellowstone Park’s superintendent Chester A. Lindsley, Marguerite was home-schooled by her mother until she was fourteen and then spent the next three years studying at Montana State College. As a teenager she spent her summers as a seasonal worker at Yellowstone giving tours on the geology and wildlife of the Park. She had plans to become a doctor, but was unsuccessful in her application and majored in bacteriology at the University of Pennsylvania instead. In 1923, she went to work in a biological laboratory near Philadelphia. In an interview in 1927 she commented that her job was indeed “most interesting and instructive,” but the pull back to Yellowstone was too strong to resist. “I could almost smell the melting snow and growing things, and feel the thrill of an early morning horseback ride,” she wrote. Marguerite gathered her savings and bought a second-hand Harley Davidson. She travelled the 2,500 miles with a girlfriend in her sidecar — both of them disguised as men — camping along the way in “hail, sleet, mud and washouts”.

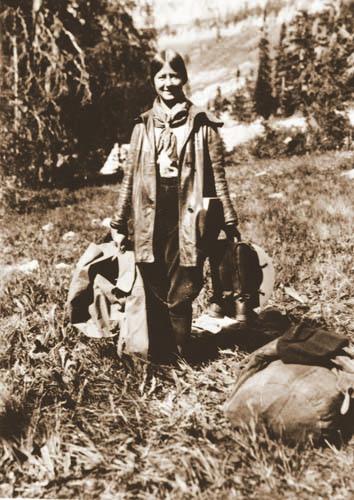

You would think that this epic cross-country trip would be the voyage of a lifetime, but Marguerite made it clear that it was only the second best trip of her life — the first being the 143-mile loop of Yellowstone that she accomplished one winter on a pair of skis. This escapade was done with another woman who lived at Mammoth Hot Springs, and the two of them were the first women to ever complete it. In 1925, Marguerite became a full-time employee — the Park Service’s, and therefore Yellowstone’s, first. She proudly pinned a badge emblazoned with a pine cone onto her uniform, which was the symbol for the Park’s permanent staff. As there were no official uniforms for female employees, Peg improvised with jodhpurs, a tailor-made green blouse with a smart green tie, riding boots, and a Stetson. She also adapted her uniform in other less obvious ways: it was said that she kept her suitors’ letters pinned to the inside of her wide-brimmed hat.

Despite her intimate knowledge of Yellowstone’s flora and fauna, there is one recorded mishap during her early years as a ranger. While on a month-long horseback trip through Yellowstone, Marguerite fell into a geyser in an area known as Artists Paint Pots. Not only did she sink up to her knees in boiling mud, receiving third-degree burns, but she was given the nicknames “Geyser Peg” and “Paint Pot Peg.” This accident, however, did nothing to deter her.

In 1926, Sunset Magazine published a glowing article about Marguerite entitled, “She’s a Real Ranger,” which spawned interest from women around the country to apply for jobs in the Park Service. Lindsley’s response was practical and not overly encouraging: “the ranger staff will be made up entirely of men,” she wrote presciently. And this was indeed true. With Albright’s retirement as Superintendent in 1933 came the end of the promotion of women to the status of Park Rangers. One official at the time stated that it was crucial for Park Service employees to be seen as “the embodiment of Kit Carson, Buffalo Bill,” and “Daniel Boone”, not “Pansy pickers and butterfly chasers” — a statement which would have horrified Marguerite.

Five years before Albright’s retirement, Marguerite married one of her many suitors: fellow Mammoth Hot Springs Ranger, Everett LeRoy (Ben) Arnold. Once again she showed her independence by eschewing a white dress in favor of “a blue gown” with “a corsage of roses.” Marguerite, like all women of the time, was not allowed to keep her full-time position once she was married, and she reverted to being a seasonal employee. She wrote: “I love the work of the rangers, and if I were a boy, I would make the park service my life’s work. It was born in me, I know it.”

The couple had a son, of which there is very little known, and for the next quarter of a century Peg and Ben carried on their tireless work in Yellowstone sharing its magnificence with all who visited. Marguerite died on May 18, 1952 at the age of fifty-one and in one eulogy she was referred to as “the breath of Yellowstone” — a reference to her intimate association with the Park. This was the woman who one night was taken over by “some primitive instinct of loneliness” which made her throw back her head and howl. She wrote: “My efforts were rewarded … I called again and another group joined the first and this time the echoes chased each other around the hills for nearly two minutes before they all died away and quiet regained.”

Marguerite Lindsley’s echo is still felt today by all the women who work for the Park Service and those who enjoy the wildness that is Yellowstone, a wildness cherished and preserved by great women like her.

Some of Horace Albright’s Other Female Rangers in Yellowstone:

Isabel Wasson hired in 1920

Miss Mary Rolfe who ran the lecture service “a fine enthusiastic girl who tried very hard to please.”

Margaret Thorne (hired in 1924)

Irene Wisdom (1924-1925)

Frieda Nelson (1925-1926)

Frances Pound (1926-1929)

Virginia Pound, Frances’s sister (1927)

Herma Albertson (1929-1933)

Leave a Comment Here