The Hippies Are Coming, the Hippies Are Coming: Missoula in the Stormy Sixties

What’s the first thing Montanans think upon hearing mention of Missoula? Usually hippies. The city wasn’t always Montana’s countercultural capital, though. In the 1960s, Missoula’s first hippies faced significant resistance. The hip community’s integration in town entailed noteworthy struggles. The haven status was earned, not granted.

Journalist Michael Fallon coined the term “hippie,” as we know it, in a 1965 article characterizing coffeehouse regulars in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury area. This new style of beatnik sought a socio-political revolution and the end of the Vietnam War. They rejected the hallmarks of American prosperity. They were idealists—romantics talking in their own lingo: “This fox, ever since she dropped out, man, she’s been on this raw food trip, dig?” They dressed wild, experimented with drugs, free love, and communal living, and listened to psychedelic rock n’ roll. Haight-Ashbury could contain the craze only so long before it burst across the globe.

In the mid-1960s, hippie trends took seed in Missoula. The city’s first (documented) Vietnam protest came on March 18, 1965. Marchers staged a walkout from the University of Montana campus to the post office for a demonstration and speeches. The event proved peaceful. That same year, a columnist for the college’s newspaper, the Montana Kaimin, described more and more students “Puffing the Magic Drag-on.”

In 1966, Charlie Artman, an LSD guru with an avant-garde folk album out, came from Berkeley, California, to speak on the UM campus. He drew an enormous crowd. As part of his visit, he sat on a drug discussion panel with the University Congregational Church’s pastor and a local pharmacist. Students listened enrapt, as Artman advocated the legalization of LSD and peyote, claimed hallucinogens boosted his I.Q., and said, “Marijuana is my think medicine.”

Missoula’s rock bands like The Gross National Product, Wayne Silversonic and the Cranustones, and The Chosen Few, were also growing more psychedelic—more San Francisco—in sound. During 1967’s Summer of Love, The Chosen Few changed their name to The Initial Shock and moved to San Francisco. There, they met the Fillmore Auditorium’s concert promoter, Bill Graham. He booked them to play alongside The Grateful Dead, Pink Floyd, Iron Butterfly, and many others. According to Missoula lore, Initial Shock could have been a household name had they not, hoping for a better deal, turned down a contract from Atlantic Records.

By 1967, Missoula’s premiere psychedelic rock venue, Monk’s Cave, had opened too. The Cave’s mystical indoor mural art was inspired by Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, a source of Beatles lyrics and ’60s counterculture favorite. The establishment booked bands from across the country. Monk’s supplied stroboscopic and liquid light shows. They hired go-go dancers. The turned-on college crowd grooved to acts like The Cobblestones from Chicago, with “hit singles” that included “Sunshine” and “Flower People,” The Real Mother Goose, and “Detroit’s Heavy Rock Group,” Speed Limit. Cocktail waitresses wore black and white miniskirts with wide black belts and knee-high black boots that shined under the chandeliers.

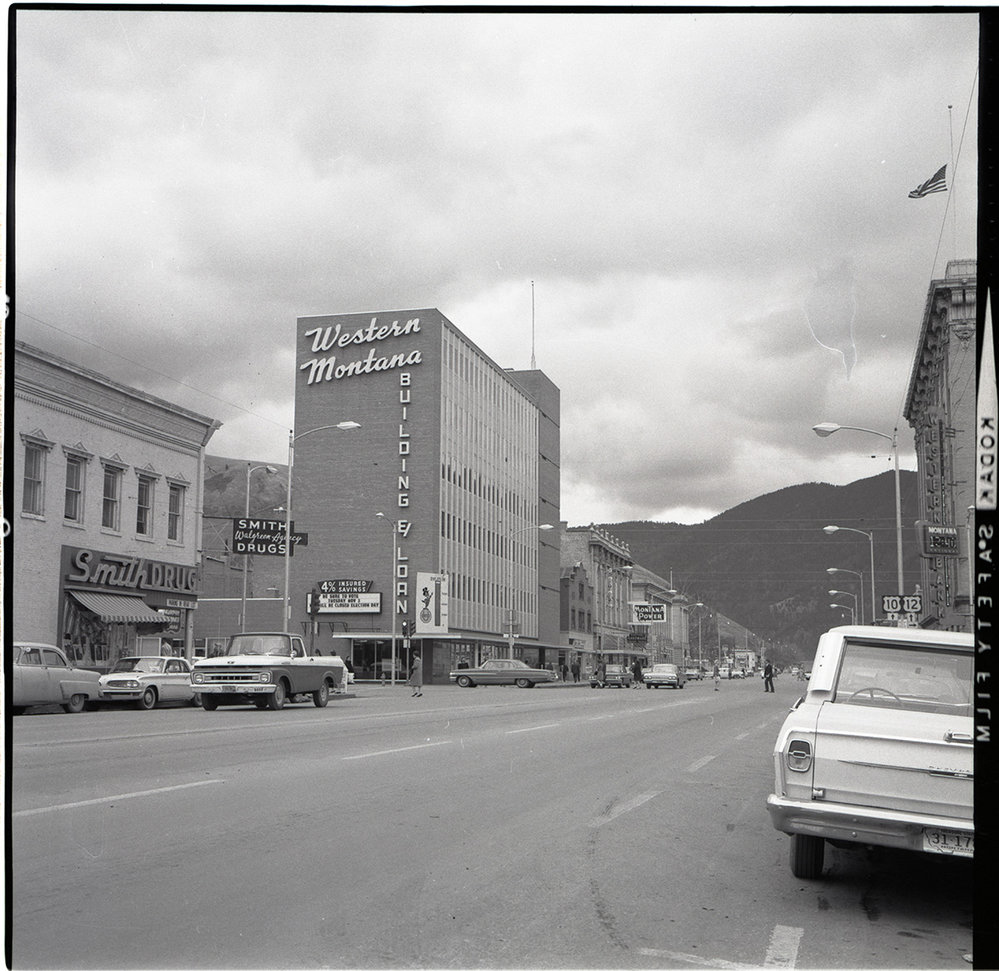

In the 1960s, the city still held more loggers, paper industry workers, railroaders, and foresters than long-haired college students. It was an industry town as much as a university town, without much radicalism in its past. Missoula’s laborers clung to the same hard work ideals as other Montanans. Hippies rejected “working for the man” altogether. Their life philosophies affronted Missoula’s traditionalist, work ethic values. And not all Missoulians sympathized with the Vietnam peace movement.

Trouble brewed on November 5, 1966, the Saturday the UM Grizzlies hosted the MSU Bobcats for the Brawl of the Wild, Montana’s biggest sporting event of the year. UM’s Committee for Peace in Vietnam organized a protest march to loop from campus through downtown. The mayor granted them a five-car police escort.

On Griz-Cat Saturday, 62 anti-war marchers turned onto Higgins Avenue, where they faced nearly 200 counter-protesters, gathered behind an American flag wrenched from a protestor. They hurled ripe tomatoes, apples, and eggs at the peace marchers. Political science instructor Emilie Loring thanked the “anonymous donor of the free egg shampoo” in the Kaimin.

Despite the police escort, peaceniks were at a loss for protection when they returned to campus. Counter-protestors ambushed them to destroy their anti-war signs and beat them.

They screamed at Artman, still in town after his speaking engagement, to go back to California. Detractors encircled and pummeled Artman to the ground. Philosophy professor John Lawry and political science professor Barclay Kuhn also caught blows.

The Committee for Peace in Vietnam met fists and hawked produce when they crashed the ROTC’s end-of-the-year commissions and awards ceremony, too, nearly inciting a riot. In 1967, they changed their name to the Committee for Intelligent Action (CIA), just in time to picket against campus recruiters from the other CIA.

From 1967 into 1968, mind-altering substances flooded Missoula. In ’66, local studies estimated around 300 pot smokers, mostly at the university. By 1968, that number neared 2,000, according to The Missoulian. For the first time, Missoula’s medical clinics saw patients suffering LSD-caused panic and anxiety. A few “acid casualties” wound up at Warm Springs state mental hospital, the paper claimed.

Parents panicked. Local authorities assumed a tough-on-drugs stance. Missoula police were said to burst into smoke-filled rooms and haul weed smokers to jail. Drugs, mostly those favored by hippies, accounted for 10 percent of Missoula felony arrests in 1967. Law enforcement complained it would have been more without the obstacle of a search warrant. County attorney Jack Pinsoneault compiled a list, through local interviews, of nearly 300 alleged pot smokers, LSD users, and suspicious people to surveil.

In 1968, 20-year-old Bill Stoianoff opened Missoula’s first head shop, the Joint Effort. The “psychedelic boutique” advertised the “heaviest selection” of stereo tapes in town, “further out than ever” posters, headbands, candles, incense, peace stickers and patches, tapestries, and beads.

Not long after the business opened, the undersheriff and a sheriff’s detective pursued 18-year-old Carolyn Padilla, a fugitive charged with felony drug possession. The chase led them to the Joint Effort’s door. They knocked. Neither of the live-in employees was home. So, they broke in through the window. Finding no one, they left—without replacing the window screen or locking the door. The sheriff’s department declared they had probable cause for breaking in without a warrant: A jail inmate told them the Joint Effort might be a good place to look!

Stoianoff and his two employees claimed they did not know Padilla beyond having seen her around. But the sheriff was convinced otherwise and asked a Missoulian reporter whose side he was on, anyway, the law or the long-hairs.

Stoianoff had his revenge. He threw the greatest hippie party Missoula had ever seen. The Blackfoot Boogie always took place on a summer full moon night at the Red Rocks swimming hole on the Blackfoot River. Popular local bands performed on one shore. Crowds listened from the other. Of the thousands of attendants, half or more were swimming, nude, or both. The free event entailed three rules: “Leave your troubles at home. Bring as much fun as you can. Remember where your clothes are.”

Of the people on county attorney Pinsoneault’s list, two presumed entries are Cynthia and Daniel Eggink. The Egginks were no weekend hippies. They came directly from Haight-Ashbury to Missoula County to “take back the land.”

Cynthia Eggink was an independently wealthy artist, dying of a brain tumor when she, with her husband Daniel, purchased a huge rural parcel on Donovan Creek, 15 miles from Missoula.

Daniel had stuck out in Haight-Ashbury as one of the first hippies to shave his head like a Zen monk. His spiritual beliefs combined Buddhism and Christianity, and he reportedly endorsed a “macrobiotic” diet consisting of nothing but brown rice. He came to Montana on California probation after a marijuana possession charge. He obtained permission to move under the condition that he report to the Missoula probation office and could not leave the county.

At the Egginks’ Donovan Creek commune, the “Native American Academy,” everyone was, supposedly, naked and armed to the teeth with guns. The neighbors grew concerned—especially when reports circulated that the Egginks planned to invite hundreds of other hippies to live at their colony. They were rumored to have a television deal and planned to book a Woodstock-style festival on their property. Shown on TV, it would attract legions of new denizens.

Less than a month after the deputy county attorney met with 20 or so neighbors to hear their perturbations about the commune, 30 officers raided the Academy and arrested eight dwellers, aged 18 to 25, for possession of marijuana. The sheriff’s department confiscated guns as well as pot.

Less than a month after the deputy county attorney met with 20 or so neighbors to hear their perturbations about the commune, 30 officers raided the Academy and arrested eight dwellers, aged 18 to 25, for possession of marijuana. The sheriff’s department confiscated guns as well as pot.

Daniel and Cynthia had been arrested the day before. Daniel got caught violating his probation, traveling to Bozeman to inquire about growing pot legally. He had to appear at the Missoula courthouse to face probation officers. Cynthia accompanied him. Before they could place Daniel under arrest, he ran, escaping onto Broadway Street. Mid-chase, Cynthia ripped a .22 pistol from her purse and threatened the officers.

As often happened in ’60s Missoula, hip people stood up for other hip people when they ran afoul of the law. Paul Melvin, a leader in the college’s Campus Reform Action Movement (CRAM) and radical candidate for president of the Associated Students of the University of Montana, decried the treatment of hippies in Missoula. He cited the Donovan Creek raid as an example of the city’s “hate campaign.” Melvin said he feared for his and other hippies’ safety.

Two days after the raid, CRAM hosted a campus rally, with impassioned speeches and live music by Three Farthing Stone. CRAM also organized the Donovan Creek Rock Festival at the University Field House to raise money to pay the bail of those arrested in the commune raid.

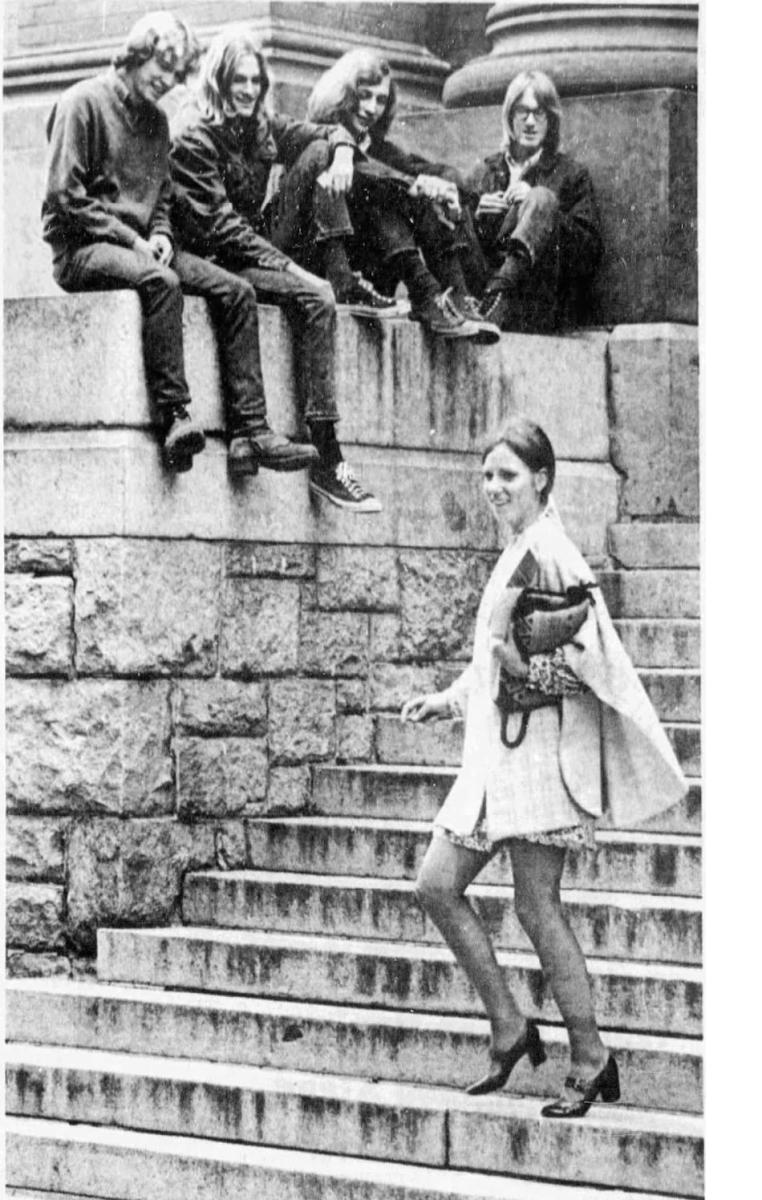

Local press from the era is packed with further reports of other young hippies hauled to jail. For every letter to the editor denouncing unfair treatment and police profiling, there are those accusing draft dodging and cowardice, calling their appearances disrespectful, or bemoaning the ways they impacted property values. For frustrated people living in frustrating times, the rebelling youth became scapegoats for any ill. Missoula hippies faced verbal abuse and beatings. Local high schools never banned men’s long hair, unlike other towns in Montana, but the look could still land you in the hospital or jail.

As the culturally turbulent ’60s turned into the ’70s and ’80s, Missoula blossomed into a true hippie haven, even as the movement ceased to exist under its original terms. Every countercultural figure from Hunter S. Thompson to Abbie Hoffman spoke at UM. Beat poets Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder showed up at a pig roast put on by Missoula’s four commune houses. Penny and Dave Bowland, whose cooking experience came from living in a commune, opened a health food restaurant called the High Mountain Café. Torrey’s offered vegetarian cuisine. Jekyll and Hyde’s and the Top Hat joined Monk’s Cave as live music hippie bars. For nearly twenty years, a billboard with a hand-painted peace sign stood prominent on Waterworks Hill. In 1974, The Grateful Dead even came to town. At the Field House, The Dead drew a crowd of 7,000. When the band left the stage after the second set, the crowd went nuts with applause. As they returned, someone hurled an Aber Day Kegger pitcher (ask your parents) that hit band member Bob Weir in the head. “Thanks a lot,” he said, and the band cut the third set short, never returning to Montana again.

Hippiedom became common enough in Missoula that detractors had to accept it as a mere fact of life. Hippies eventually won acceptance in Missoula because they won acceptance nationally. The movement successfully upended American culture, which was rebuilt after the ’60s—in accord with many hippie ideas. Legal marijuana, yoga studios, vegetarianism, liberated sexuality—they would not be as mainstream as they are today were this untrue. You can hear Jimi Hendrix at the grocery store.

Today, Missoula is friendly to the counterculture, which is a big part of the city’s identity. This would not be the case had Missoula’s first hippies not weathered the storm in the 1960s. The hippie population persisted and multiplied. Missoulians still live the 1960s’ consequences day by day.

- Reply

Permalink