The Call of Migration

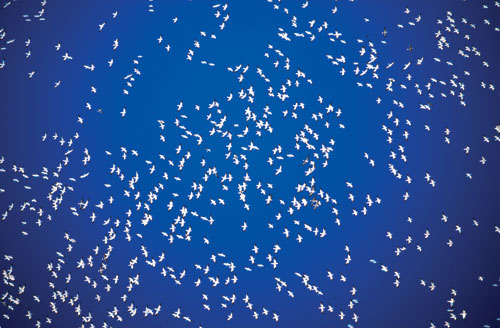

Many species of birds, fish, and terrestrial animals answer the primordial call of spring migration. Among all living birds on our planet, the sand hill crane is the oldest. Thousands of birders set their seasonal clock by the first crane sighted or the first arrow of snow geese coursing across a cobalt sky or the staccato call of a western tanager hiding somewhere in the greening bush.

In Montana, the route generally followed by birds during the spring migration comes from either the central or Pacific flyways, each of which cross over certain parts of our geography. I say generally because in the world of migrating birds few things are for certain, including the how and why the whole procession happens in the first place.

One thing we can agree on, however, is that wildlife migration routes are roughly established around physical barriers like mountains or large bodies of water. The north-south orientation of the Rocky Mountains seems important to the flight pattern of migrating birds. Also critical are the locations of feeding and resting sites along the way, including well-known National Wildlife Refuges, such as Red Rock, Lee Metcalf, Benton, Freezeout, Medicine and Bowdoin Lakes.

Once migration starts, cranes, swans, fowl, and raptors fill the daylight skies. These species use the warm energy of sunlight and the propelling thrust of thermals to help them glide along their northern journey. The larger birds are followed by song birds, many of which fly at night so as not to overheat due to the enormous energy spent and to lessen the risk of predation.

The science behind bird migration is as intriguing and baffling as the event itself. Bird enthusiasts for centuries have debated the tools used by birds to chart their course over great distances. Some authorities believe the keen sense of direction is genetically endowed. How birds orient themselves during their long flight is a complex question, which probably involves genetic programming as well as cognitive learning.

A primary physiological cue results from the tilting of the earth and the changing length of day. This adjustment activates hormonal triggers and the increase in fat buildup, which serves to energize the relentless flight. Some birds are believed to use the orientation of the sun as a compass during their journey, while others employ a combination of other tools including the detection of magnetic fields, olfactory skills, and the visible recognition of certain landmarks. Some studies point to the remarkable possibility that birds can actually see the earth’s magnetic fields.

Young birds have a particularly difficult time on their first migration. They tend to fly in the right direction by sensing magnetic fields consistent with certain latitudes, but actually haven’t a clue as to how long the journey will be. They are like a hunter with a compass and no map.

One of the most compelling legends of wildlife migration is one that took place in contemporary times—one destined to be repeated by our offspring. The legend took place some time ago in the remote site of Red Rock Lakes south of Dillon. For centuries beautiful trumpeter swans, the largest of all fowl, returned each spring to the secluded valley lakes. However, by the turn of the 20th century their voices had faded to a whisper due to commercial hunting and the draining of wetlands and marshes across the Great Plains. Finally, one tragic year only 60 birds could be found over the entire land.

One of the most compelling legends of wildlife migration is one that took place in contemporary times—one destined to be repeated by our offspring. The legend took place some time ago in the remote site of Red Rock Lakes south of Dillon. For centuries beautiful trumpeter swans, the largest of all fowl, returned each spring to the secluded valley lakes. However, by the turn of the 20th century their voices had faded to a whisper due to commercial hunting and the draining of wetlands and marshes across the Great Plains. Finally, one tragic year only 60 birds could be found over the entire land.

In the 1930s, the Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge was established to serve as the last staging grounds for the magnificent trumpeter swan, a species that once darkened the skies. So intense were the efforts to keep the swans alive during the harsh southwestern Montana winters, managers fed the swans grain. As a consequence, the last remaining population surrendered their drive to migrate.

One of the greatest dramas between man and animal followed, as dedicated scientists from the United State Fish and Wildlife Service devised a plan to teach the offspring of trumpeter swans to migrate. Today, the results of that legendary effort bear fruit each spring as birders welcome back the swans of Red Rock.

In the water, migrating trout are believed to employ olfactory skills to pinpoint certain places where travel decisions are required as they pursue that one special tributary from whence they came.

In the Flathead’s North Fork, for example, endangered bull trout and threatened westslope cutthroat are born in tributaries high in the southern Canadian Rockies. But they are reared over a hundred miles to the south in Flathead Lake. As their biological alarm goes off, the memory of ancestral beds builds and the natives are pulled upstream by the uncontrollable longing to migrate. As the journey progresses, the trout rely on a sense of smell and taste to find their special place. So precise are these senses the trout can distinguish even the slightest difference in water’s physiology. A few parts per million of one element over another is enough to chart a reliable course back to their place of origin.

Female elk, who each spring migrate to ancestral birthing grounds, in many cases return to the very place of their own birth. The females are attracted by a strong sense of community which provides protection for their offspring against marauding predators.

Each spring you can see an army of wildlife watchers in Montana’s wild places. They stand behind tripods mounted with spotting scopes or cameras in places, such as Red Rock Lakes when trumpeter swans return or Freezeout Lake when thousands of snow geese drop like so many white feathers from a clear blue sky or at the base of the Anaconda Pintler Wilderness when new elk calves pop their inquisitive heads above the sage brush.

~ Gordon and Cathie Sullivan live at the foot of the Cabinet Mountains in Libby. Gordon has been a contributor to magazines throughout Montana as a photographer and writer. Cathie is an award-winning photographer with over 25 years experience in the field of portraiture. The pair has several books to their credit, including Roadside Guide to Indian Ruins and Rock Art of the Southwest by Westcliffe Publishers and Washington Impressions by Far Country Press.

Leave a Comment Here