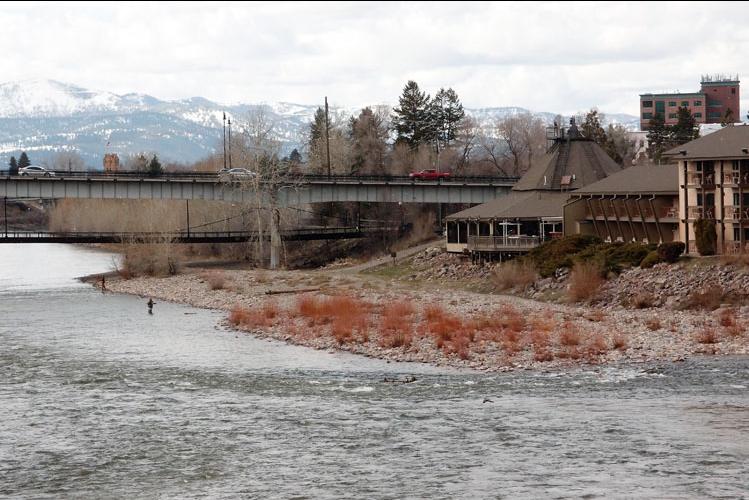

Missoula’s Clark Fork

An Urban River’s Journey of Renewal

Many of us have pasts that we want to some extent leave behind. I left the pedestrian-flooded sidewalks and the sun-blocking skyscrapers of New York City for the famous trout streams of Missoula, Montana. I hoped that my future would eclipse the past. It’s not just people who need a new beginning; sometimes it’s rivers, like Montana’s Clark Fork.

Many will argue that, with an adult, wild trout population of 300 to 500 per river mile—about one quarter the population of the Madison River—the Clark Fork is not a blue-ribbon trout stream. They say it is scarred by its past. But when I stare into the river’s glass-clear water, although I know its history of pollution and fish kills, I also hear the river’s soothing voice telling about a journey of hope and renewal.

THE RIVER’S PAST

About 310 miles long, the Clark Fork is the 7th longest river in Montana. The first non-Native American to see the lower part of the river was probably David Thompson, an English explorer, mapmaker and trader. But history left him behind and instead named the river after a man who probably never saw it, William Clark, of the famed Lewis and Clark Corp of Discovery.

About 200,000 years ago, the northern part of what is today the Clark Fork Valley bordered the southern edge of the Cordilleran ice sheet. The sheet formed ice dams and, on the site of present-day Missoula, created a 3,000-square mile glacial lake, which is about half the size of today’s Lake Michigan. Frequent ice dams flooded the future Clark Fork, sculpting much of the surrounding landscape.

The first known settlements along the river date back to approximately 3,500 BCE. By the 16th century, the settlements were inhabited by about six Native American tribes. The canyon just to the east of present-day Missoula was filled with so many human bones that early European trappers and traders named the canyon “Hellgate.”

In 1860, a trading post was established along the river. In 1866, after the Flathead Native Americans signed a treaty and relinquished much of their land, the name Hellgate was changed to the Salish tribe’s word meaning “river of ambush. Missoula with a population of about 400 had a mill for lumber and another for flour. In 1877, the U. S. government established Fort Missoula.

In 1883, the new Northern Pacific Railway fueled the town’s growth, and Missoula became a major trading center. Ten years later the University of Montana was established on the southern bank of the Clark Fork.

The Clark Fork river begins west of Butte, Montana, at the confluence of Silver Bow Creek and Warm Springs Creek. The Clark Fork travels downstream, joining several streams. When it meets the Blackfoot River, the Clark Fork’s flow doubles. As it continues its journey, the river grows wider and wider, until it flows into Idaho’s Lake Pend Oreille.

In the 1870s, copper was discovered near the headwaters of the Clark Fork. Though many didn’t know it then, the discovery was two-sided. One side led to a booming economy. Almost overnight the area became one of the largest mining, smelting, and logging centers in the world. Wealth and thousands of new jobs were created. Ornate, Victorian-style mansions lined many of the streets of Butte.

Unfortunately, the other side of the mining factor led to a hefty IOU. A steady stream of pollutants flowed into the headwaters of the Clark Fork. Then, in 1908, Mother Nature struck with The Great Flood. Water rushed through the mines, washed out most bridges, and spread toxins throughout the entire riverbed. The Clark Fork became one of the most polluted waterways in America. The insect and fish populations were decimated. By the 1950s few trout remained in the river.

After World War II, horizontal and deep-shaft mining gave way to the more economical and less dangerous open pit (surface) mining. The eventual result was the Berkeley Pit, a 1.5 mile, 1,800-foot, toxin-filled hole.

But the pit wasn’t the river’s only major problem. Unstable and highly toxic chemicals settled behind the Milltown Dam. Some of the sediments flowed through and past Missoula, keeping the fish population down. Finally, people decided to act.

Citizen organizations and federal agencies formed a conservation coalition. In 1963, thanks to the coalition’s efforts, the United States Congress narrowly passed the Stream Protection Act, giving biologists the power to review any government project that could impact a river. Ten years later, Congress passed the Natural Streambed and Land Preservation Act, giving biologists the power to review private projects. That act was eventually followed by the Superfund Act, initiating the cleanup of many rivers.

Then, in 1996, a thick ice jam threatened to destroy the Milltown Dam. The dam’s gates were opened, sending a massive amount of contamination downriver. One half of all the fish in and near Missoula were killed.

To prevent similar catastrophes and to lower the toxicity of the river, the dam, after a long, heated political debate, was removed in 2008.

Contaminated sediment behind the dam was dug up, loaded onto train cars, and then buried in waste facilities near Anaconda, Montana. The Clark Fork, upstream of Missoula, became the EPA’s most expensive Superfund site. The health of the nutrient-rich river greatly improved.

Back to the Berkeley Pit. In 1982, the Atlantic Richfield Company closed the pit because of plummeting copper prices and shut off the underground water pumps. Groundwater contaminated by the old mines flowed into the pit and caused the ore in the pit to decay, releasing more toxins. With the water rising at about one foot per year, it was projected that by 2020 the contaminated water would reach ground level and flow into the headwaters of the Clark Fork.

The Atlantic Richfield Company agreed to build the technologically advanced Horseshoe Bend Water Treatment Plant. By 2003, the plant was purifying 3.4 million gallons of diverted water before it could reach the pit.

THE RIVER’S FUTURE

In a few years, the Horseshoe Bend plant will be upgraded and begin purifying the water in the pit. Luckily, the pit’s water is rising more slowly than expected.

In the meantime, private citizens, businesses, government agencies and, of course, the Clark Fork Coalition continue to monitor the cleanup of the river. Will McDowell, the coalition’s restoration director, told me, “Our organization, along with the state of Montana, is dedicated to keeping the Clark Fork healthy and whole.” According to a recent U.S. Geographical study, toxins decreased in the river from 1996 to 2015, and the trout population slowly increased.

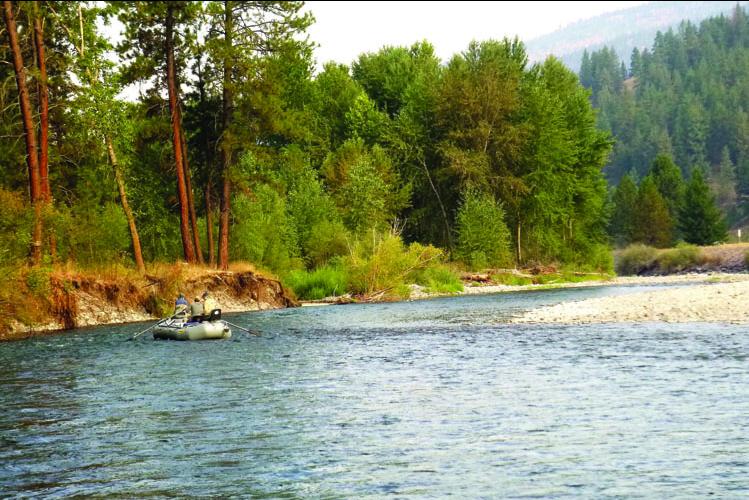

But will the Clark Fork ever become a blue-ribbon trout stream? I guess that depends on how you define “blue-ribbon.” After all, the Clark Fork, has far more wade and drift boat access points than most rivers. Because the fishing pressure is spread out, the Clark Fork has the same catch rate as the Madison River.

WHAT IF?

Often, I wonder, what if the Great Flood of 1908 hadn’t happened? What if people had known more about limiting the environmental impact of mining? Now when I fish the Clark Fork, I think of how much we’ve learned about restoring our nation’s rivers, and of how I’ve learned to savor long moments filled with the beauty of the Clark Fork.

Would we have learned so much if the dark chapters of the past hadn’t happened? This question has an answer: No, we would not have learned. So, the darkness is being changed into the light of knowledge and has value.

Leave a Comment Here