Chief Mountain: Iconic Landmark and Sacred Site

For countless generations of indigenous peoples who traversed the Old North Trail, one topographic feature was uniquely recognizable; its distinctive profile and relative isolation contributed significantly to its prominence as a landmark and sacred site. Located 4.5 miles south of the Canadian border, astride the boundary between Glacier National Park and the Blackfeet Reservation, this peak has long been known to the Piikáni (Piegan) Blackfeet as Ninaistákis or Nínaiistáko (literally "The Chief Mountain"). Its summit (elevation 9,080 feet) affords commanding views that extend more than 100 miles across the Northern Plains and, to the west, encompass an ocean of peaks deep in the heart of Glacier National Park. Conversely, Chief Mountain is visible, according to archaeologist Brian Reeves, from "the highlands southeast of Calgary (118 miles) to the north, the Sweet Pine Hills (111.8 miles) to the east, and the highlands north of Great Falls (99.4 miles) to the southeast."

A specialist in the prehistory of this region, Reeves concludes that Piikáni presence as a distinct archaeological culture "can be traced back over 1,000 years." Given their prolonged and intimate familiarity with Glacier's physical and sacred geography, the Piikáni regard Ninaistákis as the holiest mountain in their country and a source of great spiritual power. Indeed, oral history, as well as the ethnographic and archaeological records, suggest that Chief Mountain was the focal point of a complex nexus of sacred sites on Glacier's east side, which the Piikáni utilized, especially for the purpose of seeking visions. In the Two Medicine area, Running Eagle, a nineteenth-century woman warrior, received a vision in the cave behind the waterfalls that now bears her name. Ethnographic accounts indicate that vision quests were also performed on the mountains surrounding, and waters of St. Mary and Waterton Lakes, including picturesque Wild Goose Island.

Stone structures built by would-be visionaries constitute the one surviving physical signature of this deeply rooted religious tradition. These "fasting beds" are typically oval or U-shaped and consist of stacked rock slabs, with an opening to the east. Anthropologist Clark Wissler examined one of these structures on the crest of a hill near Two Medicine River and, in a 1912 monograph, listed its inside dimension as "about five feet by three and three in height, just large enough for a man to lie in with some comfort." Reeves and Peacock conducted a comprehensive study of the distribution of vision-quest structures in portions of Piikáni territory. By 2001, they had identified "five ancient structures on Chief Mountain, over fifty on both the nearby and distant mountain tops," and more than 100 such structures in Glacier and Waterton Lakes National Parks.

Predictably, some revelations received during vision quests inspired the advent of important religious icons and rituals. For example, the Beaver Bundle is the largest, most ancient and most revered Nitsitapii (Blackfeet) medicine bundle. The preponderance of evidence from oral history suggests that it was conveyed in visionary form by the Beaver People at Waterton Lakes. Similarly, the origins of Medicine Pipe bundles are attributed directly to communications from Thunder. According to an account provided in 1905 by Brings-Down-The-Sun, a North Piikáni holy man, the Long-Time-Pipe, which is the oldest Piikáni sacred pipe, was visioned long ago at Ninaistákis.

References to Chief Mountain first appeared in the historic record during the 1790s. Peter Fidler, a fur trader for the Hudson's Bay Company, spent the winter of 1792-1793 at a Piikáni village in the foothills of southwestern Alberta. On December 31, 1792, he became the first white man to observe Chief Mountain, which his guides identified as Nin nase tok que or "the King." Based on information compiled by Fidler, Aaron Arrowsmith, a British cartographer, produced the first maps (1795-1796) that identify Chief Mountain and depict its relative position in the Northern Rockies. In 1802, Arrowsmith crafted a more detailed map of the Upper Missouri and adjacent portions of the Saskatchewan River basin, which incorporated data from maps that Siksiká (Blackfoot proper) chiefs created for Fidler. Therein, the "Heart" (Heart Butte) and "King" (Chief Mountain) were the only peaks represented for this section of the Rockies. Arrowsmith's second map became an indispensable resource for subsequent cartographers and was meticulously consulted in preparation for the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Meriwether Lewis may have seen Chief Mountain from Camp Disappointment on July 22, 1806. Located along Cutbank Creek, approximately 12 miles northeast of present-day Browning, this site was the northernmost point at which the Corps of Discovery encamped. Weather conditions, however, were heavily overcast and often rainy throughout the extended stay of Lewis's party, which may explain the absence of journal references to observations of Chief Mountain. Documentary evidence of Euroamerican contact with Ninaistákis does not surface again until the 1850s, when James Doty, a surveyor for the U.S. Pacific Railway Expedition, and members of the British North American Palliser Expedition viewed the mountain in 1854 and 1858, respectively.

The preeminent status of Chief Mountain in Blackfoot sacred geography is illustrated by the experience of James Willard Schultz. In October 1883, he accompanied a group of hunters to the St. Mary lakes area. Profoundly impressed by his first close glimpses of the Rocky Mountains, Schultz inquired about the names of peaks visible from their vantage point. Sol Abbot informed him that "only that farther one in sight ahead, standing out as though in the lead of the others, (whose east face formed) an almost sheer cliff," was named. After learning that it was called Nina Istukwi ("Chief Mountain"), Schultz concluded that "never had a mountain been more appropriately named."

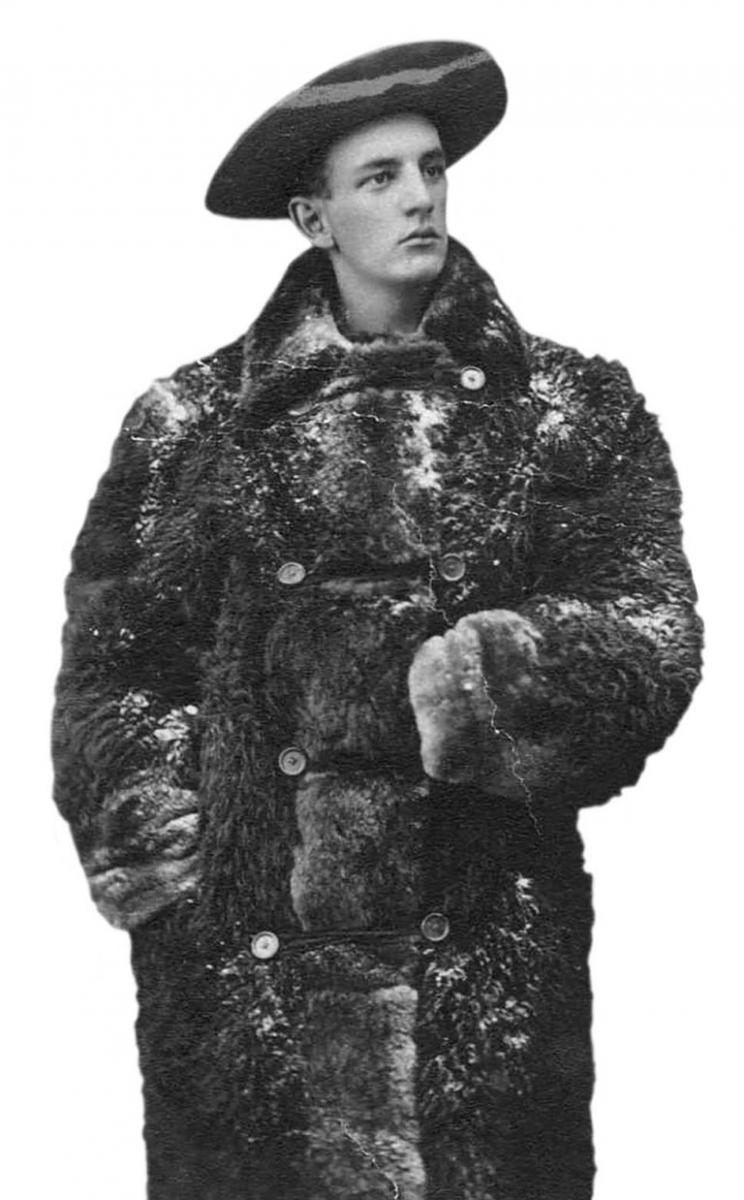

The first detailed account of Chief Mountain appeared in an article published in 1895 by Henry L. Stimson. Almost fifty years later, as Secretary of War, he directed the Manhattan Project to fruition. In September 1892, however, Stimson was a member of the first non-Indian party to climb Ninaistákis. At its summit, they discovered evidence of the mountain's long history of ceremonial use. On terrain far too rugged for bison to traverse, three bison skulls were found, two of which were so old "that the black sheaths of their horns had been worn away by winds and storms, and the sheaths of the other horns had turned from black to yellowish white."

Their Piikáni guide, Paiota Satsiko ("Comes-with-Rattles"), told them that these relics were used as pillows during vision quests. After learning of Stimson's findings, Schultz asked Ahko Pitsu ("Returns-with-Plenty"), a knowledgeable source on Piikáni history, for more information about the skulls. Ahko Pitsu explained that his friend and adviser, Miah, took one of them to Chief Mountain's summit, where he found two others, including "the fasting pillow of that powerful, long-ago warrior, Eagle Head." Oral history apparently did not preserve the identity of the other supplicant.

Stimson climbed Ninaistákis again in 1913. He arrived just as two men were breaking camp, following a successful ascent of the mountain. In conversation with the young climbers, Stimson recounted his previous experience and asked them if they had seen a bison skull on the peak's summit. As proof of their discovery, one climber revealed the skull described by Stimson, who then proceeded to share the story associated with its use. Perhaps feeling a sense of guilt about disturbing a religious relic, the climber gave the skull to Stimson, who reburied it deep among rocks on the summit. Stimson ultimately returned from Chief Mountain "satisfied that the old chief and his totem would sleep in peace hereafter."

For readers who are more interested in Chief Mountain as a scenic attraction, this area is the premier fall-foliage destination in Glacier National Park. If weather conditions are favorable, fall color in Glacier usually peaks during the last week of September and/or first week of October, except for western larches, which typically climax in late October. Among the extensive stands of aspens and cottonwoods found east of the Continental Divide, the largest, by far, is located at the base of Chief Mountain, which, in autumn, towers more than 3,000 feet above an electrifying carpet of yellow. The panoramic grandeur of this landscape can be viewed most effectively from a pullout on Chief Mountain International Highway (Montana Route 17), only 2.2 miles from its junction with U.S. 89.

This crescendo of color, unfortunately, is fleeting, particularly if winds, which so frequently buffet the Rocky Mountain Front, prematurely strip aspens of their foliage. Nevertheless, naturalist Paul Schullery observes that the soil here is apparently "so accommodating that the species thrives in great abundance—grove after grove of gnarled, dwarfish trees with the tiny leaves that characterize aspen in its most extreme environment."

At peak color, this spectacle will deeply inspire you, albeit in a fundamentally different manner than generations of supplicants experienced when, after days of fasting and incessant prayer, they received supernatural revelations at Ninaistákis. Fortunately, this masterpiece of Nature's artistry still can be viewed in absolute solitude from the pullout identified above.

Leave a Comment Here