They didn't call 'em 'Horseboys'

In the golden age of matinees, eager children lined up outside the movie theater each Saturday. There would be a rollicking cartoon, a portentous-sounding newsreel, but mostly, there would be a Western.

The younger children bounced anxiously in their seats as brave cowboys rode at top speed across a landscape miraculously free of prairie dog holes. The older children imagined they were in the saddle. They pursued the men who robbed the stage. They caught the men who robbed the bank.

Cowboys saved the rancher’s beautiful daughter from the suave villain who wanted to buy the ranch because it would be worth a lot when the railroad came through. Some of the older boys even imagined saving the rancher’s beautiful daughter for reasons more romantic than heroic. Some of the girls imagined they were the rancher’s beautiful daughter; some imagined they rescued themselves.

Where were the cows?

In most of those old Westerns, cows were bit players.

They had their uses, of course. A daring cowboy galloping up to rescue a small child from a stampede of, for example, chickens, wouldn’t have been nearly as impressive.

Somehow, the point was missed that the frontier cattle industry was about cattle. They were the reason cowboys spent weeks and months riding across grassy western plains. They were the reason ranchers bet their future on a bunch of ruminants. They were one of the reasons land agreed upon by treaty with the western tribes was gradually taken away.

So what, exactly, is cow? Humorist Ogden Nash wrote, “A cow is of the bovine elk. One end is moo, the other, milk” What’s in between is actually pretty interesting.

Historically, humans discovered the value of cattle long before they found a use for horses. At least 8000 years ago, cattle were providing meat, milk, and muscle for the Bronze Age people of present-day Turkey and the Levant. Oxen were pulling plows in Mesopotamia while horses were nothing more than competition for vegetation.

An ox, by the way, was simply a former bull of any breed which was not... uh... made into a steer until it attained the age of three. That gave it the shoulder strength of a bull but the docility of a steer. In time, any bovine used to pull a wagon or plow might be called an ox—even a cow.

When humans first made use of horses, they merely cross-bred them with donkeys to create mules. When horses were finally domesticated, it was to pull chariots in battle. Like the bold cowboy on his fiery steed, the bold Roman in his wildly careening chariot is a common image of the past.

Except for the comic convention of a snorting bull chasing someone up a tree, the tragic image of the exhausted bull facing the matador or the rousing nighttime stampede of a frightened herd, there seems little drama about cattle. Writers have even been known to describe a character’s blank look as that of “bovine stupidity.”

Cows are smart. Don’t laugh. When a human shows wisdom, people often call it “horse sense.” When a horse is particularly good at working cattle, it has “cow sense.” That seems to put the intelligence of the cow on top.

Certainly they aren’t smart by human standards. They are, after all, not human.

Why should we be surprised when a cow can’t seem to figure out how to get through the correct gate? Cows don’t build gates, or fences.

Why should we think cows are stupid when they are up to their bellies in deep grass but break out of the good pasture as soon as they’ve eaten their fill? Cattle know that if they graze in one place for too long the grass will be gone. They practiced pasture rotation millennia before humans figured it out.

Why should a cow fight you when you are just there to give antibiotics to her sick calf? After all, the last time you handled her calf, it ended up with a stinky brand on its side.

Cows have intelligence for the species of animal they are. On a cold, windy day at calving time, two cows may lie down with their heads nearly together and flanks forming a deep “V.” Their calves curl up snugly in the protection thus formed. Furthermore, when cows go to distant water, they may leave their sleeping calves for a while, but they always leave a”babysitter” cow to watch over the youngsters.

Cattle were herded thousands of years before there were horses for the herders to ride. The question arises: Did cowboys actually need horses?

Well, no, but it wouldn’t have been nearly as colorful without them.

By the 1830s, the American Fur Company had cattle in eastern Montana. There are those who claim these were the first, but in history, it’s wise to be skeptical about “first, only, biggest, finest, most,” and any other superlative. Historical memory tends to be very provincial, and if you’re not careful you can really put your foot in it. And when you’re talking about vast herds of cattle, that’s something to avoid.

Tens of millions of bison had ranged America before the 1800s. They still ruled the western plains in the days of the fur trade, but they were nearly gone by 1880. Rich prairie grasses stretched out for hundreds of miles, just waiting to be grazed.

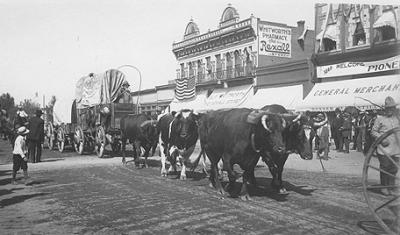

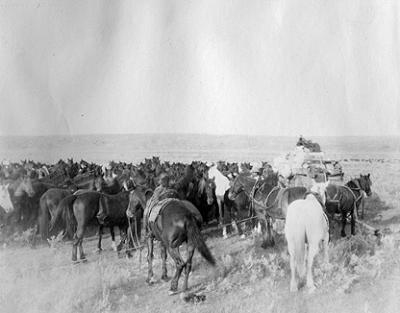

By 1885, over a million head of cattle were grazing in Montana Territory, mostly on the eastern plains. Montana stockmen divided these common ranges into roundup districts containing hundreds of thousands of acres each. Every rancher having cows in a particular district was responsible for participating in the spring and fall roundups when everyones’ cattle were gathered.

These were exciting times for the cowboys. They were often very young and very full of the image already fixed in the public imagination through dime novels.

Some were farm boys, some had been raised in the ranching tradition, and some were fresh off the train from the East.

Humans can’t be taken out of the ranching picture, because without humans, ranching wouldn’t exist. Cattle would simply be cattle, as jackrabbits are simply jackrabbits, and rattlesnakes are simply rattlesnakes.

The horses could go, however, although they’d probably carry the colorful cowboys off with them. The Montana Peak hat, the silk bandana, the fancy spurs, woolly chaps, and the vest with its pouch of Bull Durham tobacco tucked in a pocket would have been unnecessary.

Those high-heeled cowboy boots? Forget them. That heel was designed to keep a boot from slipping through the stirrup and trapping the cowboy’s foot. But as Nancy Sinatra didn’t sing, “Those boots weren’t made for walking,” you wouldn’t want to walk a mile in their shoes.

Speaking of shoes; except for oxen, whose hooves wore down as they pulled wagons along hard-packed roads, cattle did not need to be shod.

With herders on foot, the ranges would necessarily have been smaller. Instead of tens of thousands of head of cattle mingling on a vast common range, there would have been smaller herds kept in smaller districts.

It takes a lot of range to support cattle, but horses eat even more than cows, since their digestive systems aren’t as efficient. Back in open range days, every big cow outfit typically supplied 10 to 12 horses for each of the dozen or so cowboys working in each district. A general rule of thumb is that it takes two tons of hay to feed a horse through a Montana winter and only a ton and a half for a cow. Take the horses away and the land could have supported at least 130 more marketable cattle per roundup crew.

Horses did come in handy once ranchers started raising more hay for winter feed, but the draft horses’ work of mowing, raking, and stacking has long-since been taken over by machines. Machines have not yet managed to generate a tender ribeye steak, milk, cheese, or ice cream.

In the final analysis, horses added to the efficiency and romance of the open range, but they were like the fancy flourishes on a sheet of calligraphy: Nice, but the story was about cowss

~ Montana native Lyndel Meikle has spent several decades being educated in the ways of cattle. She is a national park ranger, historian, occasional blacksmith and a really bad housekeeper.

Leave a Comment Here