Butte, America - Montana's Mining City

For better and worse, so much about Butte contradicts our stereotypes of Montana as the “Last Best Place.” Although its rough and tumble origins were not unlike dozens of other mining camps in western Montana, Butte quickly transfigured into something completely different, and it has largely remained so ever since. In its profound mineral wealth and explosive metamorphosis to a gritty industrial city; in its tremendous ethnic diversity and violent labor radicalism; in its breathtaking roller coaster economy and now disreputable status as nation’s largest environmental wasteland; and in its still unbroken spirit, Butte is fantastically and tragically incomparable with the rest of the Treasure State.

In April of 2006, the Secretary of the Interior recognized this fact and officially designated Butte as the centerpiece of one of the largest historic districts in the country. Encompassing 9,774 acres and more than 6000 buildings, structures, and sites that contribute to an almost palatable character this is—fittingly—no typical historic district.

“Like Concord, Gettysburg, and Wounded Knee, Butte is one of the places that America came from,” writes journalist Edwin Dobb. Chapter after chapter of the nation’s unfolding saga are connected with, and can be explained by, this complex and always compelling place. According to the National Park Service, the Butte-Anaconda National Historic Landmark is “a unique and outstanding part of America’s built environment” that “possesses exceptional value in illustrating the dramatic changes that resulted from America’s emergence as the world’s leading industrial nation.”

Butte’s influence extended well beyond Montana’s borders. Indeed, the town’s meteoric rise to the pinnacle of world copper production was inherently linked with the advent of the Age of Electricity and the corresponding industrial revolution of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Providing vast reserves of red metal just when it was needed most, once-booming Butte played a key role in transforming the United States into a modern economic superpower.

No wonder its residents still proudly refer to their historic city as “Butte, America.”

Butte’s unique geology concentrated unparalleled mineral wealth in one geographically precise location—a furrowed outcropping at the north end of the Summit Valley that was appropriately nicknamed “the Richest Hill on Earth.” In no other single metal mining district in the United States was such a small area worked so intensively for so long. From the 1860s until the present day, mining has continued unabated in Butte’s immediate vicinity.

Three distinct metal booms—first gold, then silver, and finally copper (supplemented by zinc, lead and manganese)—defined the area’s history. Between 1880 and 1993 Butte produced staggering wealth, including nearly 3 million ounces of gold, 709 million ounces of silver, 855 million pounds of lead, 3.7 billion pounds of manganese, 4.9 billion pounds of zinc, and an incredible 20.8 billion pounds of copper.

It all got started back in 1864, when the glint of gold in a prospector’s pan attracted hundreds to the banks of Silver Bow Creek. Observers, such as Charles Warren, described the ramshackle destination as a “deplorable” place, crawling with armed men and degraded by “hurdy-gurdy houses and the ‘wide-open’ gambling dens.” The initial gold boom had busted when the first census takers arrived in 1870 to discover that only a handful of resolute miners remained.

Silver resuscitated Butte’s less-than-certain future. Hundreds returned when governmental demands transformed the near ghost town into one of the nation’s most significant hard rock mining districts. By 1876—the year Custer met his fate in eastern Montana—developers platted Butte’s Original Townsite and dreamed of the possibilities.

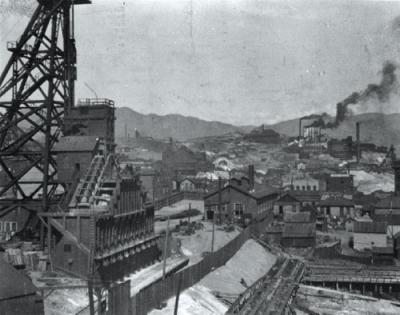

In the years that followed, thick, black streams emanated from Butte’s smelter smokestacks, providing a gritty countenance to what some observers labeled as “the ugliest city in America.” Still, property values rose steadily and by1880 Montana’s most prosperous city claimed 3,363 residents.

Butte’s earliest residential neighborhoods clustered on the steep hill north and east of the central business district. There sagebrush gullies, russet-colored waste dumps, and mine yards carved out small, irregular lots like puzzle pieces. Steep, twisting streets followed contour lines and gulch bottoms, and the simple cottages of Irish and Cornish miners co-mingled with early employers like the Anaconda, Neversweat, St. Lawrence, and Parrott mines.

In the 1880s, several events bolstered Butte’s rapidly industrializing economy. The mining center became the seat of Silver Bow County in 1881 and later that same year the Utah and Northern Railway linked the city with an emerging national marketplace. Within months, Marcus Daly discovered the world’s largest supply of copper ore at the 300-foot level of his Anaconda mine.

In the amazing decades that followed, Daly, and competing Copper Kings William Andrews Clark, and Fritz Heinze, transformed Butte into a formidable mining center. Sensing opportunity, Daly and his investors planned the townsite of Anaconda, some twenty-six miles west of Butte. There they developed a state-of-the-art smelting facility that propelled Butte and the Anaconda Company to national prominence. By August of 1885 the sister cities accounted for 41% of the nation’s total copper output and a Pacific Coast promotional magazine dubbed Butte “the largest, busiest and richest mining camp in the world . . .”

The antithesis of the small, rural, conservative and Protestant communities that still typify most of the Big Sky Country, Butte had become what writer Joseph Kinsey Howard once called the “black heart of Montana.” It was a kind of industrial island—more a Pittsburgh than a Denver or Salt Lake City—smack dab in the middle of an otherwise largely undeveloped Montana wilderness.

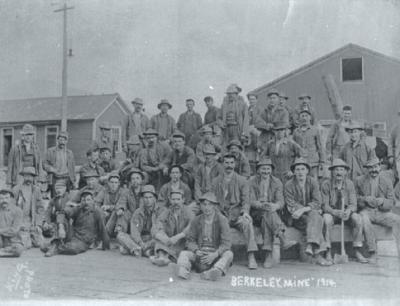

By 1890, the boisterous copper metropolis of nearly 11,000 boasted over 80 operating mines, 4,000 industrial and service workers, and some of the strongest unions in the entire country. Birdseye views depict a beehive of activity. Around the city center, at Park and Main Streets, elaborate brick buildings, two to eight stories high, symbolized the city’s power while giving shape to an impressive skyline. Above it all loomed the mighty Anaconda Hill, which author Gertrude Atherton described as a “tangled mass of smokestacks, gallows-frames, shabby grey buildings, trestles . . . looking like a giant shipwreck.”

As the nineteenth century waned, and the Anaconda Company successfully monopolized the Butte Hill, always arriving masses of foreigners made Butte one of the most ethnically diverse localities in the trans-Mississippi West. Fully 70% of the city’s population were first or second generation immigrants. At the turn of the century, it had a higher percentage of Irish than any other city in America—a fact that was acknowledged when Irish President Mary McAleese recently visited the city. New immigrants from Finland, Serbia, Croatia, Italy and dozens of other nations came too, giving an even richer flavor to an ever-changing cultural landscape. From these deep pockets of ethnicity sprang schools, churches, lodges, stores, saloons, and boarding houses, all of which gave Butte the Old World patina of an eastern industrial city ten times the size.

Butte’s male-dominated labor force was insatiable. A red light district flourished between Main and Arizona along Galena and Mercury Streets. By 1893, the City had licensed 16 gambling halls and 212 “drinking establishments,” many of which had no key to the front door because they were open 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Growing prosperity also drew many Asians from abandoned mining and railroad camps throughout the West, and an active Chinatown thrived just west of the tenderloin. Herb emporiums, noodle parlors, laundries, and other shops crowded streets, and lined a vibrant network of paved alleys, between Colorado and Main Streets.

By 1910, the greater Butte area was home to an estimated 90,000 residents—more than twice the population of any other city between Spokane, Salt Lake City and Minneapolis. The city’s notable economic and political stature was symbolized in the construction of still more civic and commercial buildings of monumental scale and notable architectural character.

During World War I, copper production and population levels peaked. A booming economy gave rise to many larger middle and upper class neighborhoods in the western and southwestern portions of the city, where less mining took place. Here, two to three-story high-style Queen Anne, Italianate, Shingle, Classical Revival, and Craftsman houses—including several high-style mansions designed by the state’s best architects—stand interspersed with far more modest Victorian cottages, pattern-book Bungalows, duplexes, and fourplexes.

When the nation’s copper economy slipped into the doldrums following “The War to End All Wars,” Butte’s status as the centerpiece of the multinational Anaconda Company began to wane considerably. Meanwhile, the Company’s holdings in Chile continued to expand, ultimately eclipsing its Montana operations in 1938.

Although still a notable producer until the early 1980s, Butte-Anaconda never regained its former status as a highly integrated copper producing system. The nationalization of many of the Anaconda Company’s Chilean properties in the early 1970s nearly bankrupted the corporation and led to its purchase by the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) in 1976. ARCO closed the Anaconda smelter in 1980 and the Butte mines in 1983.

Today, Butte is, in some respects, a shadow of its former self. What once was an urban metropolis of nearly 100,000, is now struggling to reach 40,000 residents. And, what once was the world’s greatest mining center is now one of the largest environmental cleanup areas in the nation. A generation after ARCO shut down, the toxic scars of Butte’s mining legacy are still clearly evident. They will always remain a potent reminder of the negative byproducts of extractive industry and an unbridled quest for economic gain. It is a story worth remembering.

But Butte—that exceptional city in the most unlikely of places, that uncommon place of constant interest—is also a living reminder of all that was gained in the name of this great sacrifice. Without Butte, it is unlikely that America would have electrified, modernized, and risen to the ranks of an economic superpower as quickly and effortlessly as it did. Without Butte, untold thousands of immigrants and millions of their descendants might not have set foot in the land of the free and enjoyed the fruits of its bountiful harvest. Without Butte, America may never have been that great “Arsenal of Democracy” that helped the Allies taste victory in two World Wars. And without Butte, Montana would be something completely different than it is today. In experiencing Butte, we are afforded an opportunity to remember Montana’s complex past—one that defies the one-dimensional stereotypes and reaches out beyond its borders to shape the character of the entire nation.

Visit Uptown Butte on Saint Patrick’s Day, stroll through its gallery walks on a warm summer’s evening, dance the chicken dance at its accordion festivals, have a drink at the M and M on New Year’s eve, taste a pasty at Gamers, ride the Copper King Express from Anaconda to Butte, experience it all and you will recognize one thing unmistakably—Butte, despite its hardships and its scars, is a spirited survivor that will always be remembered. Its rich heritage and enduring strength of character are palatable wherever you go, and it is precisely these defining traits that now inspire Butte to remake itself yet again.

Today, as has been the case so many times before, Butte is actively celebrating its heritage while transitioning to an energetic, sustainable economy. The recent designation of Butte-Anaconda National Historic Landmark District will hopefully serve as the basis for increased tourism in the region. Already Butte’s Main Street revitalization program is hard at work promoting heritage tourism and in other ways invigorating the economy. Several investors have purchased and renovated older landmarks in the historic uptown area, while filmmakers and artists are flocking to drink in the ambiance of Montana’s cultural treasure. Even Montana Tech, Butte’s School of Mines and Engineering, is spearheading one of the foremost environmental reclamation programs in the country. Making the most of what you have got has always been central to Butte’s continuing story.

Ever proud and feisty, Butte is undoubtedly one of the most dynamic, determined, and memorable communities in Montana. Its past is unforgettable, and something tells me its present and future will be likewise.

Leave a Comment Here