DASH

Department Literary Lode

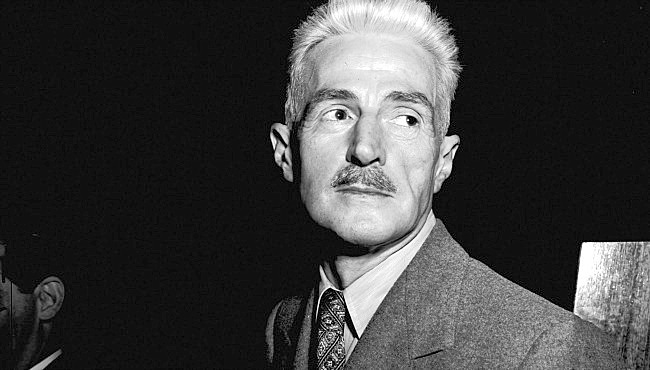

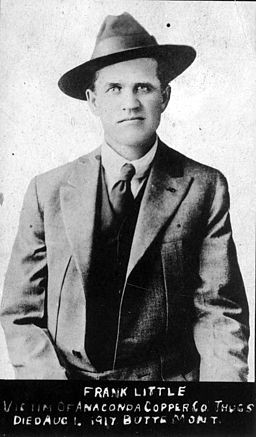

Before his writing career got underway, mystery novelist Dashiell Hammett (The Maltese Falcon) worked as a Pinkerton detective for several years, including a detail to Butte in 1917. On Aug. 1, 1917, labor leader Frank Little was lynched in the streets of Butte after trying to organize a strike against the Anaconda Mining Company. The following is a fictional account of what might have happened if these two lives intersected.

Little came out of the boarding house in his underwear.

No, not “came.” Pulled. Dragged. The first of the skin peeling from the tops of his toes where they caught the sidewalk, the curb, the street. On the other foot, his cast scraped and rumbled in sympathy.

Eight men pulled like plowhorses, heading for the Cadillac, while the lady who ran the boarding house stared at us from behind the curtains in her first-floor parlor. She watched like we were some sick, sober version of the Keystone Cops.

None of us were doing this for laughs. This was serious Company business in the dead of night.

Likewise, none of us were the law. I came the closest, but even then I don’t know how far the agency, not to mention the Old Man, would back me if I said I was there as a curious bystander.

“Wrong place, wrong time, Hammett,” the Old Man would say.

I couldn’t disagree.

The plowhorses grunted, the cast rumbled, and the jerked-from-his-sleep gentleman stayed silent as the grave.

I looked past the boarding house at the city built on the hill. It was an ugly town in an ugly notch between ugly mountains, all of it dirtied by poison smoke that settled in a grit you could never completely clean.

Eight men pulling one man, barely out of his sleep grog. Still in his long underwear, his union suit. More than a dozen hands seized the rabble-rouser with grips strong as handcuffs.

I was one of the eight.

I’d been told to expect a big payoff if I went along. I never said “yes,” but I never told them “no,” either. I was in wait-and-see mode.

One of our posse gave a hard shove to his back and a couple of us lost our hold on him. Little stumbled, tried to catch up with his legs, but couldn’t. It took him a while to get back on his feet. No one helped him.

A heavy man with a cork-blackened face said, “Yer lookin’ a little wobbly today, Red.”

They laughed. Not me. There’s nothing funny about setting a table for a poison meal.

“Where’s your Commie spit and vinegar now, Red?” the blackface stranger said, his voice a sack of gravel dragged over railroad ties. He was talking politics, not hair color. The little man in his underwear—Little by name and little by physical frame—had no hair to speak of. The sparse strands were thin and wispy as cornsilk. The skull beneath was shaped like an Edison bulb. Not so bright on this still-dark morning, though.

Me, I was a Pink, a Pinkerton—and, in truth, closer in political hue to Little than any of these other men, large and dumb as stallions, would ever be. These were Company men, loyal miners, warmongers, full-blooded Americans, haters of hyphenates. At that moment, they were the most dangerous men in Butte.

Frank Little, all six feet and 135 pounds of him, had arrived in the city two weeks ago like an iron-heeled boot stomping a hornet’s nest.

The Company newspaper printed nearly everything he said, but cast his words in a coppery light. Little had come out strong against the war, telling the city’s mine workers, “I don’t give a damn what this country is fighting. I am fighting for the solidarity of labor.”

In response, the newspaper editorials said, Little “sought to terrorize this state’s industry with his traitorous harangues.”

These were touchy times in Butte, just as they were in Bisbee and Fresno, other towns where Little had roused the rabble with his talk of wages, a shorter workday, and safer conditions. To the mine owners, Frank Little was a thief—of money, of production,

of weak-willed men. The time had come to shut him up, to teach him a lesson and send him packing back to IWW headquarters, or parts unknown.

The heavy blackfaced man opened the Caddy’s passenger-side door. The others shoved Little inside without so much as an inviting “Get in” or a helpful “Watch yer head.”

Two of the men slipped in beside him on the back seat, one on either side.

I climbed in the front, Blackface got behind the wheel and the other four gentlemen in our party followed in another car.

For the next fifteen minutes, we rode up and down the steep streets while Frank Little received the beating of his life in the back seat.

I wanted no part of it. Not any more.

I stared out my side of the car as we passed the black skeletons of the mine headframes, large as dinosaurs. There were dozens of them all over this hillside city. The smelters had yellowed everything into uniform gloom. A smokestack, straight as a cigarette, poured sulfurous clouds from its hot depths. Everywhere I looked, men moved in and out of the mineyards in a steady stream, one shift replacing another with round-the-clock efficiency. There was no shortage of underground men in Butte.

I listened to the whipcrack of fist on flesh coming from the back seat and I wondered if Little thought it had been worth it.

After a time, Blackface said he was bored with driving in loops and suggested we up the ante.

He stopped and we got out of the car, all of us. Little sagged between his two new best friends from the back seat. I could see he was beyond halfway gone. He hadn’t said anything during our tour of Butte, not one word as we passed the mines and their men, just the occasional groan that somehow slipped past his clenched teeth. He was one tough hombre, I’ll give him that.

Now he lifted his drooping head and fixed his eyes on mine. Why he should pick me and none of the others, I’ll never know. I’ve been told I look like someone who’ll listen.

Little raised his face, looked at me and, with great effort, said, “Tell them.”

That was it. The last two words of Frank Little. They came out of his mouth accompanied by a spray of blood, a thin mist like you’d get from a perfume bottle at the counter in Hennessy’s.

Blackface took two steps toward the unionist, cocked back his right arm, and struck Little just under the eye. That punch was so loud dogs could hear it on the other side of the city.

Frank Little collapsed once and for all. Blackface caught him by the armpit then hoisted him like a sack of coal. “Now,” he said, “let’s finish this.”

One of the men got a coil of rope from the back seat of the other car.

They trussed Little head-to-toe, then tied the other end of the rope to the back of the Cadillac.

I saw which way the wind was blowing now.

Everyone else got back in the cars. Everyone except Little and me.

The first light of the day, muted and gray, appeared on the east ridge of the mountains surrounding Butte. It was just enough light for me to make out the crumple of clothes, limbs, and white cast behind the lead car. I was sorry for what was about to happen.

Blackface looked out the driver’s side, saw me standing in the street, and said in no uncertain terms, “Get in.”

“Think I’ll catch the next trolley, boys,” I said brightly.

Blackface started to say something like “I don’t think you heard me” or “Wise guy, huh?” but he was interrupted by a commotion in back of the car. It was Frank Little, struggling to stand. He got as far as his knees.

One of the men leaned forward from the back seat and said, “Forget this wiseacre, Middleton. Let’s just go.”

Blackface put the car in gear, but before he accelerated down the street, he gave me one more narrow-eyed look, and said, “Take care, Pink.”

I knew then I was a marked man and started calculating how fast I could get out of town.

The second car beeped its horn. “All right, already,” Blackface roared back at them. He shook his head at me—one last warning—then he gave the Caddy all the gas in the world.

And me, I stood there watching them go down the street, picking up speed as they went.

I didn’t turn away soon enough. I got it all: the rising roar of the engine, the high girlish hoots from inside the car, the bouncing mangle of a body, the plaster chips flying off the cast like white sparks.

Then they turned a corner and I went back to my room to pack my bags.

Leave a Comment Here