Keeping Accounts: Ledger Artists Celebrate the Blackfeet in Montana

They are two artists whose work focuses on the Blackfeet people in Montana, but there’s one story from Blackfeet history that neither of them has painted: a tragic case of mistaken identity that played out on the plains near Shelby.

It happened January 23, 1870, as troops of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry led by Major Eugene Baker were looking for a Blackfeet leader named Mountain Chief—a great-great uncle of Montana artist John Isaiah Pepion, as it happens. A member of Mountain Chief’s band had been accused of killing a white trader. But Baker made a colossal blunder: He thought he’d found Mountain Chief, but instead, his troops attacked a peaceful village led by a man named Heavy Runner. They killed about 200 people in one of the most shameful incidents of the Indian wars. Montana-born artist Terrance Guardipee is descended from Heavy Runner through one of his sons, Last Gun, who escaped the slaughter.

The Baker Massacre—what many Blackfeet call Bear River Massacre because they would rather not speak Baker’s name—is still too vivid and raw for Guardipee to paint. Pepion has never painted it either. But that event joins Guardipee and Pepion in a common task as artists: Celebrating Blackfeet identity and remembering what has happened in the Blackfeet country of Montana and Canada. Their art is rooted in the land where the bands of the Blackfeet confederacy have lived for generations.

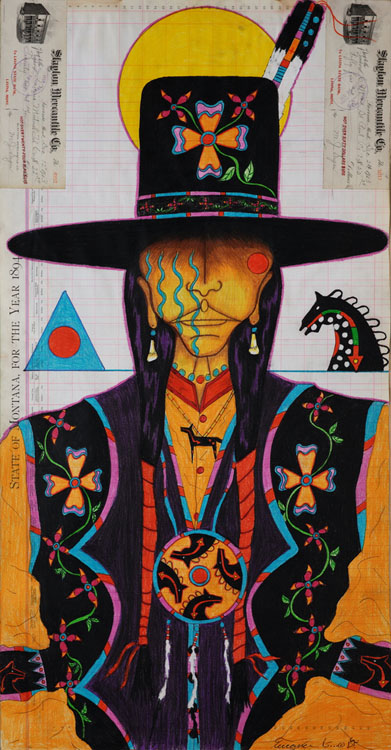

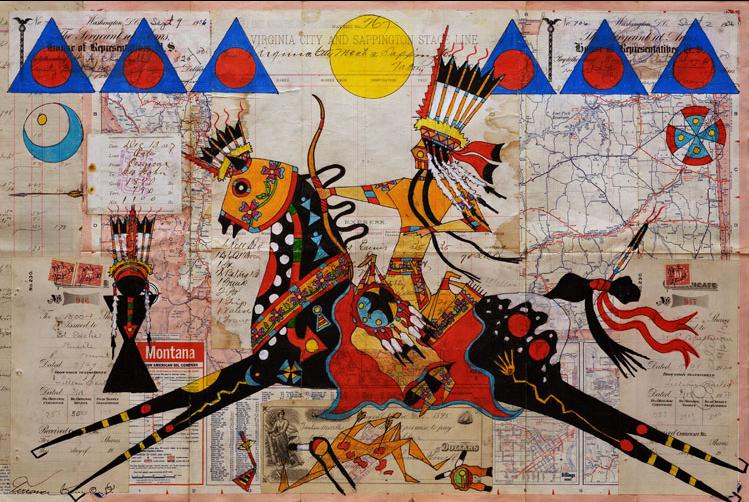

“The land is very significant. You’ve got Sweet Grass Hills, you’ve got Glacier National Park,” Guardipee said. “We considered that was where the Creator lived. And we have Chief Mountain there, which is our sacred mountain. So when you see my art, you’ll see these triangle designs with dots in them. Those are mountain designs, they represent the backbone of the world, which is now Glacier National Park. It’s a very, very significant place to us.”

Ledger art: a definition

Guardipee and Pepion, who are relatives, both grew up in the Browning area, where Pepion still lives, and both studied at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. Guardipee lives now in Issaquah, Washington, near Seattle, but revisits Montana often.

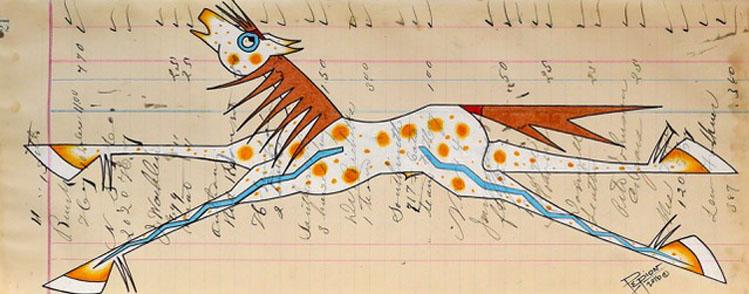

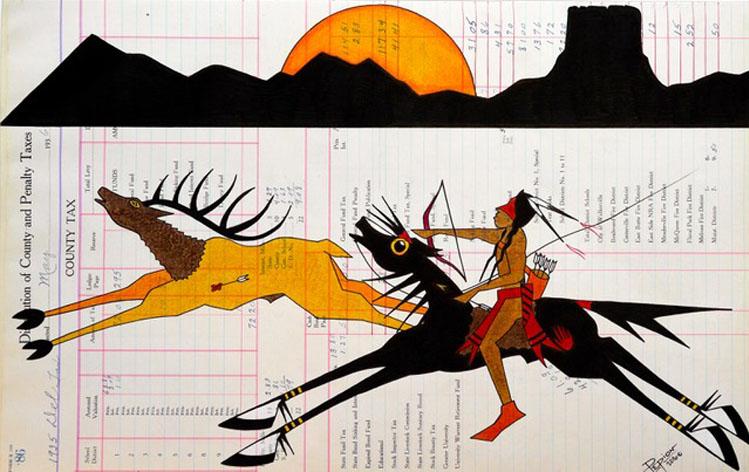

Though neither Guardipee nor Pepion confines himself to a single genre, both are known partly for their work as ledger artists. The term “ledger art” comes from 19th century warriors’ practice of narrating their exploits by drawing on any kind of paper they could acquire, including settlers’ account books. Plains Indian warriors once drew those two-dimensional pictures on animal hides. But whites realized that Plains tribes had adopted a new medium for their art when they began to recover paper ledgers containing warriors’ drawings from battlefields on the southern Plains in the 1860s.

Early ledger art was largely about individuals’ accomplishments in battle or the hunt. The genre grew after the U.S. government confined men of the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Arapaho, Comanche and Caddo tribes at Fort Marion, Florida, in the 1870s. There the artists learned that the mainstream culture was interested in their drawings—not just about battle, but about Plains village life.

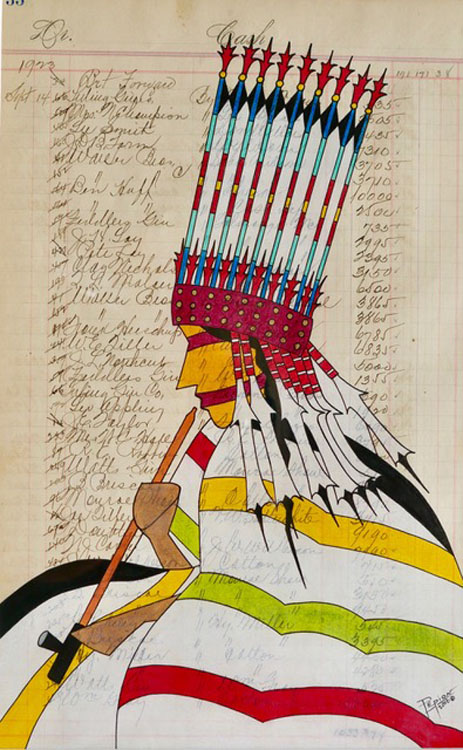

Ledger art went dormant as artists of that generation died, but it revived in the last decades of the 20th century. Many contemporary artists still use historic ledger paper, making their art into a kind of dialogue with the history recorded in those documents.

For example, one of Pepion’s ledger drawing shows a Blackfeet warrior on a green horse plunging a lance into the shoulder of a buffalo, and the wounded animal is lunging toward a paper-straight horizon marked Cash, one horn hooking a handwritten notation of a deposit by a certain Rob’t Newton. It’s a page from a merchant or banker’s account book from the 19th century, originally intended for noting the transactions of people with ordinary names such as Nell Garfield—how the West was settled, line by line, transaction by transaction.

But the superimposed image of the green horse and rider chasing the bison across the page is a 21st century Blackfeet artist’s repurposing of the commercial documents of an earlier era to show that the Northern Plains, the Rocky Mountain country, can’t be reduced to names and numbers in columns. The buffalo culture of the Blackfeet confederacy still flourishes in Pepion’s art.

The warrior’s task

Pepion still draws the same kinds of pictures of warriors on horseback that Blackfeet artists drew before 1900, but some of his riders have switched mounts to keep up with the times.

“I’ve been doing warriors on bikes, warriors on motorcycles, warriors in cars,” he said. “Nowadays, things are way different. I can’t go out on a horse raid or go count coup on another enemy. There are different ways to be warriors now, like getting an education. For me, being a warrior is through art.”

And the fights those modern Blackfeet and other American Indian nations fight nowadays, Pepion says, are about issues such as oil and water and poverty—the kind of eastern Montana oilfields theme that emerges in Pepion’s 2014 piece of ledger art, Indian Girl Lost In A Man Camp.

Guardipee draws real figures from history such as Mountain Chief and a noted Blackfeet woman warrior named Running Eagle. She’s the person for whom Running Eagle Falls in Glacier National Park is named.

Picturing the land

Those who study historic ledger art say there was little attention to the landscape of real places in those drawings. The background was often just a vague setting in which to show the warrior’s exploits.

But both Guardipee and Pepion say the land is hard to keep out of their drawings, especially the mountains that give Montana its name.

“Where I’m from, mountains are part of our culture, and I believe it’s where we get a lot of our power from,” Pepion said. “One mountain particularly you’ll see in my art is called Chief Mountain. People believe that’s where Thunder lives, and it’s a really sacred place. That’s where we go to have vision quests and fast.”

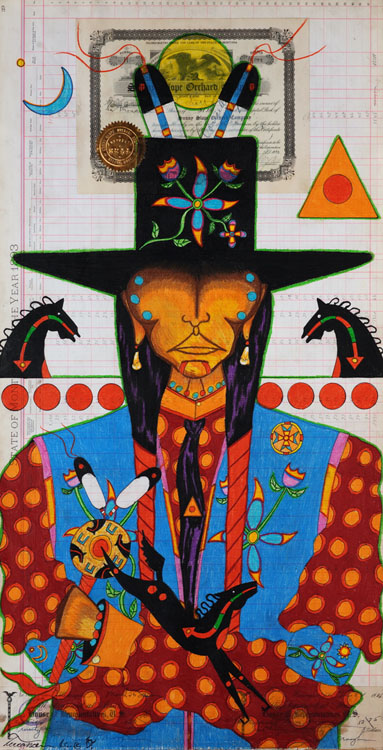

Guardipee deliberately seeks out historic documents from Montana. Besides his drawings, he makes collages, sometimes on old highway maps or gas station maps of Montana. He also uses stock certificates from railroads and mining companies in Montana, old checks, war ration books, Great Northern train memorabilia, music paper, old wall maps from Montana schools.

“I tried to collect documents from all the various communities where I knew my tribe would have migrated through the area before those communities even existed,” Guardipee said. “I started using pretty much any old document I could find that I think my ancestors would have used if they had had an opportunity to acquire those things. It really makes my collages come alive because of the history of the state of Montana and the communities around Montana.”

That includes areas around Virginia City, Red Lodge, Missoula, Helena, Great Falls, Butte, Anaconda, points elsewhere.

Pepion, similarly, mentions the Sweet Grass Hills, Chief Mountain and Heart Butte Mountain as places that influence his art. Sometimes he’ll also paint the less majestic—little Birch Creek, for example, which runs near his family home.

Power

Both Pepion and Guardipee will use, with permission, Blackfeet designs from tipi covers or other traditional art. Pepion uses colors he associates with the Blackfeet, although he prefers to call his people Piikani, with that spelling.

“I have particular colors based on a lot of the colors in a lot of our beadwork. I just like the colors that are comfortable being from this place—the land, the skies, the beadwork.”

Pepion adds that he is also influenced by the 19th century art of one of his ancestors, Big Brave, that same Blackfeet leader whom the American military knew as Mountain Chief.

“When I do horses sometimes, there will be a green horse or a blue horse or a red horse. How I got those horses that color is from Big Brave’s winter counts and war records. He did a lot of horses that color,” Pepion said.

Guardipee’s art uses the same tools 19th century Blackfeet artists used, but he allows himself the full range of 21st century colors.

“I use what they used back in the old days, colored pencils. I’ll outline it with a black ink, the same way they would have done it back in the old days. The only difference is, I have hundreds of colors to pick from, so my images can be very bright, real bold, powerful colors,” Guardipee said. “I want it to be powerful and electrifying and give off the feel of energy and power.”

Another source of that energy is embedded in the paper.

“The paper’s very powerful; it has a lot to say, especially when it comes to Montana. I try to use all Montana paper as much as I possibly can because so many things happened in the state of Montana with the Blackfeet and various other tribes that lived there,” Guardipee said.

- Reply

Permalink