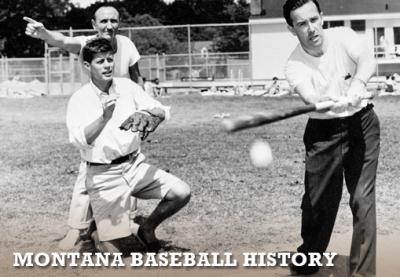

Montana Baseball History

The first Montana native to make it to the majors did so in a way that would make his home state proud. Players called him loyal and hardworking. Beat writers respected him. He was so admired in the game, he ended up meeting with three different presidents during the course of his career — with Theodore Roosevelt before a game in 1910, with William Howard Taft during a campaign stop in 1912, and with Woodrow Wilson in the White House over a casual conversation about baseball in October 1913.

Never mind that Frank James Burke — most often referred to as “Brownie and best known for standing just four feet, seven inches — started out as a mascot. Despite his small stature, the Marysville native ended up making a big impact on the national pastime.

Perhaps it’s fitting that Montana’s first contribution — and one of its most memorable connections — to Major League Baseball would be so unusual. It almost had to be. The Treasure State is far from a hotbed of major league talent; its ball fields are still under snow when pitchers and catchers report to spring training in Florida and Arizona every year, and those fields often remain buried well into the first months of the Major League Baseball season. This sort of geographic disadvantage is part of the reason so few players ever jump from Big Sky Country to the big leagues — 22 over the last 143 years — or former major leaguers retire to this remote part of the northwest. In fact, when a baseball Web site called FlipFlopFlyin.com researched the American town farthest from a Major League Baseball team — it led to Turner, Montana, population 192, situated about four hours north of Great Falls.

But that’s why Burke’s story is so perfect. Born in 1893, less than four years after Montana achieved statehood, he was the fourth of eight children in a large Irish-American family.

His father worked as a carpenter and his mother as a housewife, but the community of Marysville revolved around the gold- and silver-rich Drumlummon Mine. When the mine started to dry up, the family moved to Helena, where Brownie thrived. According to his biography by the Society of American Baseball Research (SABR), Burke “managed the routes of the two competing Helena daily newspapers and, once, when a popular play arrived in town, he purchased all of the tickets to then resell at profit.” As an 11-year-old in 1905, he began the first of at least four winters as a page in the Montana senate. He also served as a drum major in Butte’s celebrated Boston and Montana Band, with which he traveled throughout the West to perform in competitions.

In 1909, the precocious Burke was working as a bellhop at West Yellowstone’s Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel when he caught the eye of Cincinnati Reds president August “Garry” Herrmann.

(SABR allows for the possibility that the two had met previously, through their affiliation with the Elks.) “Impressed by the lad’s outgoing, confident demeanor, Herrmann offered him the role of ‘continual mascot’ with the Reds, contingent upon parental approval,” wrote Phil Williams for SABR. “Brownie wrote his mother, obtained her blessing, then traveled eastward to catch up with the Herrmann party in Chicago. On August 3, 1909, owner and mascot arrived in Cincinnati.”

According to a story in the Cincinnati Post, Burke, just 16, made his on-field debut five days later.

At the time, it wasn’t unusual for baseball teams to employ men of small stature as “mascots.” The now politically incorrect practice stemmed from the antiquated belief that midgets and dwarfs, as they were known then, brought good luck. “Lefthanders, hunchbacks and cross-eyed people were all considered [lucky],” wrote Harold Seymour in The Golden Age of Baseball. “Touching a hunchback was popularly believed to bring good luck.”

But mascots like Van Zelst and Burke became more than just superstitious sideshows. He worked more as a batboy than, as SABR put it, “a magical charm.” He suited up for each game, delivered fresh balls between innings to the umpires and organized equipment for the Reds’ players. Before a July 24, 1912 game, he helped Cincinnati pitcher Frank Smith warm up. The Cincinnati Post reported the next day that Burke couldn’t catch Smith’s spitter, much to the amusement of opposing pitcher and future Hall of Famer Christy Mathewson.

Burke also helped off the field, becoming something like Herrmann’s assistant. When a player was released, Burke delivered the message straight from the owner to the player. Former Reds manager Joe Tinker, after being fired from the team in 1913, told the Cleveland Plain Dealer he believed Burke spied on players away from the ballpark and reported his findings to Herrmann.

During Cincinnati’s off-season, Burke stuck by Herrmann’s side at social events. He accompanied the owner on trips to the World Series, performed at the owner’s country club and made those three appearances with sitting presidents. His banter with President Wilson caught the attention of the New York Times, which wrote about the exchange on October 16, 1913. After Wilson good-naturedly ribbed Burke for Cincinnati’s lackluster showing in the season standings, the mascot remarked about the president to the paper, “He’d make some baseball manager.”

Simply put, people liked to be around Burke. His showmanship and natural gregariousness would eventually lead to Burke’s departure from the Reds, and with the financial and moral support of Herrmann, his pursuit of an acting career.

Success followed Burke during stage productions. In letters on file at the Baseball Hall of Fame, Burke wrote Herrmann, “I’m going to telegraph [Montana’s] Senator [Thomas] Walsh again and if he can’t do anything to hasten my going into service, I’m going to pull my freight and go to Canada where I’m pretty certain I will have my chance.”

Burke was enlisted into the Ninetieth Infantry Division, Headquarters Detachment, on June 1, 1918, and began serving overseas a few weeks later. In typical fashion, he made a quick impression. American Legion magazine wrote in a 1940 article that “every solider and the Germans in Berncastle knew this little fellow.” After the war, Robert Ripley of Ripley’s Believe It or Not credited Burke as “the shortest man during World War I serving in the AES,” according to the Helena Independent Record.

Burke was considered the first native son to make the majors, arriving at least five years before St. Louis Cardinals pitcher and Cascade-born Rees “Steamboat” Williams, who has long been recognized as the state’s trailblazer to the bigs.

“Alas, such an opportunity for baseball immortality eluded Brownie Burke, and he is largely forgotten today,” wrote Phil Williams for SABR. “During his half-decade in baseball, however, his wide-ranging role with the Reds made him one of the sport’s most public figures. By all evidence it was a very happy existence, one a turn-of-the-century boy from a remote, working class background could only dream of.”

That’s the thing with Montana baseball stories: they don’t always make Ken Burns documentaries, end up on the pages of Sports Illustrated or lead off Sports Center, but like the state itself, they tend to reveal overlooked or underappreciated treasures. These stories help create the fabric of the game and provide a window into not only the history of baseball but the state of Montana itself.

For a game that’s long captured the nation’s imagination, there’s plenty of material to draw from — even way out here in left field, in Montana.

[This excerpt is from the introduction to the book with the same name, published by The History Press, 2015]

Leave a Comment Here